This chapter should be cited as follows:

Muriithi FG, Odubamowo KH, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.413363

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 10

Common obstetric conditions

Volume Editor: Professor Sikolia Wanyonyi, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Chapter

Post-term Pregnancy and Intrauterine Fetal Death

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The average duration of human pregnancy is traditionally estimated to be 280 days (40 weeks) from the date of the last menstrual period (LMP).1 However, in practice, a pregnant woman is considered to be at ‘term’ when her pregnancy reaches 37 weeks with the 6-week duration between 37 and 42 weeks considered as normal term gestation.2

The reported incidence of pregnancies that continue beyond 42 weeks' gestation is estimated at between 4 and 10%.3 The estimate varies with the method used for pregnancy dating.4 This chapter explores the definitions, clinical significance, diagnosis, and management options of post-term pregnancies.

DEFINITIONS

The descriptions: “post-term”, “post-dates pregnancy” and “prolonged pregnancy”, are commonly used, often interchangeably, to describe pregnancies that continue beyond 42 weeks. In recent times, a pregnancy that lasts for 41 weeks and up to 42 weeks has been described as “late-term".

According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), a post-term or post-dates pregnancy is defined as one which continues beyond 42 completed weeks after the first day of the last menstrual period.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF POST-TERM PREGNANCY: INCIDENCE AND FACTORS INFLUENCING THE ACCURACY OF GESTATIONAL AGE ESTIMATION

Globally, the reported incidence of pregnancies that continue beyond 42 weeks' gestation varies between 4 and 10%.3 The incidence of post-term pregnancies decreases as the accuracy of the dating criteria used increases. The methods for gestational age and due date estimation include calculation from the date of the LMP for spontaneously conceived pregnancies, and the date of embryo transfer for pregnancies conceived by assisted reproduction, the most reliable method is by ultrasound measurement of the embryo in the first trimester up to and including 13 6/7 weeks of gestation.4 Most of the evidence on the use of ultrasound for gestational age estimation is derived from high-income countries where an early ultrasound is a standard component of antenatal care; for low-income settings, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least one ultrasound before 24 weeks' gestation.5

Other factors that may impact the accuracy of gestational age estimation include late booking for antenatal care (or late presentation to first antenatal visit), menstrual cycle irregularity, or recall bias.6 High body mass index (BMI) and fibroids may also hinder the accuracy of gestational age estimation by fundal height measurement.7

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although the most common cause of prolonged pregnancies is inaccurate dating, when post-term pregnancy truly exists, its cause is usually unknown.8 Epidemiological studies have identified a positive association between post-term pregnancy and advanced maternal age, nulliparity, high BMI, previous post-term pregnancy, male fetus, hormonal factors and genetic predisposition.8,9 Certain fetal conditions, such as anencephaly and placental sulfatase deficiency, are associated with post-term pregnancies.10

The mechanisms for the initiation of labor and timing of human parturition have been studied in an attempt to understand how to prevent preterm and post-term birth, both of which are associated with poor perinatal outcomes but have so far remained a mystery.11,12

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF POST-TERM PREGNANCY

Postmaturity syndrome was originally described by Clifford and was characterized by loss of subcutaneous fat reserves and meconium staining caused by placental dysfunction.13 Since its description, studies have shown an association between post-term pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes. Over time and with the increased use of obstetric ultrasound and better definition of terms used to describe adverse outcomes such as stillbirths, researchers realized that the adverse perinatal outcomes related to post-term pregnancy were underestimated.8

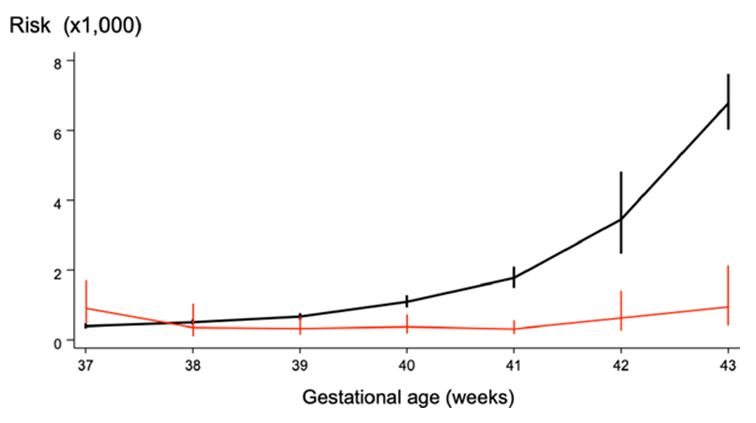

The perinatal mortality rate at 42 weeks of gestation is approximately double that at term (4–7 versus 2–3 per 1000 deliveries, respectively). Furthermore, it increases 4-fold at 43 weeks and 5–7-fold at 44 weeks. When fetal and neonatal mortality rates are calculated per 1000 ongoing pregnancies, there is a sharp increase in fetal and neonatal mortality rates after 40 weeks gestation8 (Figure 1).

1

Perinatal mortality per 1000 ongoing pregnancies. Reproduced from Hilder 1998,14 with permission.

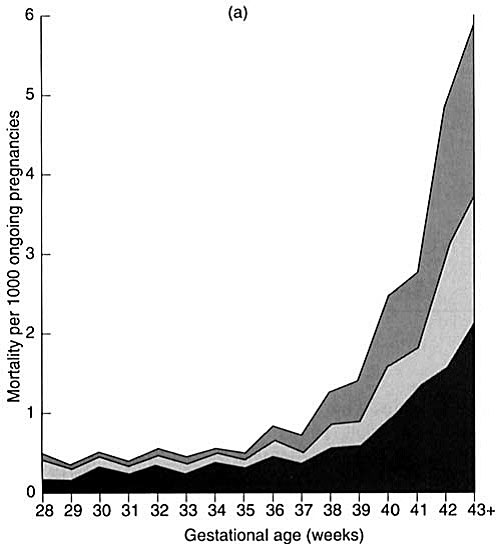

Regarding stillbirths, the most important independent risk factor for stillbirth is intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Growth restriction is associated with stillbirth in 52% of cases at any gestational age, and when unrecognized, it contributes to an estimated 10% of perinatal mortality in Europe.3 The post-term fetus with IUGR is particularly at risk of stillbirth. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 million pregnancies, established that the risk of stillbirth at term varies between 1.1 and 3.2 per 1000 pregnancies and there is a steady increase in stillbirth rates beyond 37 weeks' gestation (Figure 2).15

2

Prospective risk of stillbirth per 1000 pregnancies and risk of neonatal death per 1000 deliveries by gestational age in pregnancies continued to term. Reproduced from Muglu et al. 2019,15 with permission.

Post-term pregnancies that continue beyond 41 weeks are also associated with meconium aspiration syndrome, neonatal academia as demonstrated by low umbilical cord pH levels, low 5-minute APGAR scores, neonatal encephalopathy, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), fetal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, clavicular fractures, and higher infant deaths in the first year of life.3,8

Post-term pregnancy is associated with significant risks to the mother which include: labor dystocia (9–12% versus 2–7% at term), severe perineal lacerations (3rd and 4th degree tears), related to macrosomia (3.3% versus 2.6% at term), operative vaginal delivery, doubling in cesarean section (CS) rates and the attendant complications (14% versus 7% at term), and maternal anxiety.8

MANAGEMENT OF POST-TERM PREGNANCY

Despite efforts to improve pregnancy dating and gestational age estimation,4 a significant number of pregnancies continue beyond term and are at risk of adverse outcomes. As a result, most countries have guidelines advising on elective labor induction at late-term.

The guidelines are mainly based on the recommendation of a Cochrane review on “Induction of labor in women with normal pregnancies at or beyond term” that concluded that “a policy of labor induction compared with expectant management is associated with fewer deaths of babies and fewer cesarean sections”.2

Despite the findings of the Cochrane systematic review, the actual timing for induction is still a subject of debate. In actual practice, the timing of induction varies from one setting to another and amongst specialists in the same setting with a range of between 39 and 42 weeks.16

Regarding the choice of either elective cesarean section or induction of labor, a WHO-led multi-country secondary analysis of survey data advised on avoidance of elective cesarean delivery due to an increase in NICU admission compared to either expectant management or induction of labor. The recommended choice, therefore, is between expectant management or induction.17

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies consisting of 7261 cases assessed maternal and perinatal outcomes after elective induction of labor at 39 weeks in uncomplicated singleton pregnancy, concluded that “Elective induction of labor in uncomplicated singleton pregnancy at 39 weeks’ gestation is not associated with maternal or perinatal complications and may reduce the need for cesarean section, risk of hypertensive disease of pregnancy and need for neonatal respiratory support”.18

The INDEX trial was a multicenter randomized, non-inferiority trial of 1801 low-risk women. It compared induction of labor at 41 weeks with expectant management until 42 weeks in low-risk women concluded that “the study could not show non-inferiority of expectant management compared with induction of labor in women with uncomplicated pregnancies at 41 weeks; instead a significant difference of 1.4% was found for risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in favor of induction, although the chances of a good perinatal outcome were high with both strategies and the incidence of perinatal mortality, Apgar score <4 at 5 minutes, and NICU admission low”.19

A multicenter trial that assessed the perinatal and maternal consequencies of induction of labor at 39 weeks among 3062 low-risk nulliparous women found that induction at 39 weeks did not result in a significantly lower frequency of a composite adverse perinatal outcome, but resulted in a significantly lower frequency of cesarean delivery rates.20 This approach, however, was not found to be cost-effective.21

A review of evidence and guidelines by the ACOG acknowledged that late-term and post-term pregnancies are associated with an increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality. ACOG guidelines recommend induction of labor after 42 0/7 weeks and by 42 6/7 weeks of gestation.10 This recommendation is similar to a previous review of guidelines.3

Other recommendations by the ACOG include interventions that decrease the incidence of late-term and post-term gestations such as accurate gestational age determination and membrane sweeping.10 Routine membrane sweeping is supported by the findings of a Cochrane review for the reduction of post-term pregnancies.

A Cochrane review found that “sweeping of the membranes, performed as a general policy in women at term, was associated with reduced duration of pregnancy and reduced frequency of pregnancy continuing beyond 41 weeks (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46–0.74) and 42 weeks (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.15–0.50)’’. However, clinicians are advised to consider the balance of maternal discomfort over avoidance of other induction methods.22

An updated systematic review covering the period 2005–2016, evaluated the efficacy and safety of membrane sweeping in promoting spontaneous labor and reducing a formal induction of labor for postmaturity. Its findings are summarized below:

Membrane sweeping is advantageous in promoting spontaneous labor (RR 1.205, 95% CI 1.133–1.282, p = <0.001), and reducing the formal induction of labor for postmaturity (RR 0.523, 95% CI 0.409–0.669, p = <0.001).23

The review concluded that the above effect is significant from 38 weeks of gestation, and is not dependent upon the number or timing of membrane sweeps performed.23

One trial, the SWEPIS trial, was stopped early due to a significantly higher perinatal mortality rate in the expectant group. It was a multicenter open-label randomized superiority trial of 2760 women with low-risk uncomplicated singleton pregnancies which compared outcomes between induction of labour at 41 weeks versus expectant management until 42 weeks. It concluded that induction of labor at 41 weeks is associated with decreased risk of perinatal mortality compared to at 42 weeks.24

Regarding increased antepartum surveillance for post-term pregnancies, ACOG, on the basis of observational data, recommends antepartum surveillance for post-term pregnancies especially to detect oligohydramnios as it is associated with adverse fetal outcomes.10 Evidence for routine fetal surveillance such as cardiotocography and biophysical profile for post-term pregnancies is lacking.

CONCLUSION

There is significant evidence that post-term pregnancy, i.e. pregnancy lasting beyond 42 weeks, is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Efforts should be made to encourage women to book for antenatal care early in the first trimester to accurately date pregnancies with the most accurate method available. Accurate dating is likely to reduce the incidence of post-term pregnancy, and as a result, improve on the timing of interventions when indicated. Options such as membrane sweeping should be discussed with women as part of their pregnancy care plan and should be revisited if women do not deliver by term. In the absence of widespread consensus on the timing of delivery, it is recommended to aim for delivery of all women by 42 weeks' gestation, as the data show an exponential rise in adverse outcomes after 42 weeks' gestation. Based on existing evidence on outcomes following induction of labor timed at between 39 and 41 weeks in comparison with expectant management, and higher costs when induction of labor is offered at 39 weeks compared to expectant management, individual clinicians together with their patients should undertake a shared decision-making process, taking into account local capacity of healthcare systems, healthcare resources, and patient preferences regarding the recommendations.20,21

For now, it seems prudent for healthcare systems to offer induction of labor at around 41 weeks so as to achieve a good balance between achieving the best outcomes in the most cost-effective manner.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Encourage women to book for antenatal care early in the first trimester, so as to improve on the accuracy of gestational age estimation.

- Inform mothers during the discussion on timing of birth or induction of the additional small but increased risk of stillbirth with advancing gestational age.

- Discuss membrane sweeping with women opting for expectant management after 40 weeks' gestation.

- Offer either expectant management or elective induction of labor for gestations between 41 and 42 weeks.

- Rule out intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and oligohydramnios for women opting to have expectant management beyond term.

- Aim to have all women delivered before 42 weeks' gestation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Jukic AM, et al. ‘Length of human pregnancy and contributors to its natural variation’. Human Reproduction 2013;28(10):2848–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det297. | |

Middleton P. ‘Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term (Review)’. 2018;(5). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007372.pub3. | |

Mandruzzato G, et al. ‘Guidelines for the management of postterm pregnancy’. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2010;38(2):111–9. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2010.057. | |

Pettker CM. ‘Methods for Estimating the Due Date Committee on Obstetric Practice American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine’. 2017;(700). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28426621. | |

WHO. ‘WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience’. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;41(1):102–13. doi: 10.1002/uog.12342. | |

Unger H, et al. ‘The assessment of gestational age: a comparison of different methods from a malaria pregnancy cohort in sub-Saharan Africa’. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884–018–2128-z. | |

Morse K. ‘Fetal growth screening by fundal height measurement’. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Elsevier Ltd., 2009;23(6):809–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.09.004. | |

Galal M. ‘Postterm pregnancy’. Facts Views & Vision in ObGyn 2012;4(3):175–87. doi: 10.1002/9781119979449.ch23. | |

Roos N. Patophysiology of postterm Pregnancy Epidemiology, risk factors and cervical Ripening, Karolinska, 2012. Available at: https://openarchive.ki.se/xmlui/handle/10616/41018. | |

ACOG. ‘Management of Late-Term and Postterm Pregnancies’. Practice Bulletin 14 2015. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25050770. | |

Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. ‘Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes’. Science 2014;345(6198):760–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1251816. | |

Menon R, et al. ‘Novel concepts on pregnancy clocks and alarms: Redundancy and synergy in human parturition’. Human Reproduction Update 2016;22(5):535–60. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw022. | |

Clifford S. ‘Postmaturity, with placental dysfunction; clinical syndrome and pathologic findings’. J Pediatr 1954;44(1):1–13. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13131191. | |

Hilder L. ‘Prolonged pregnancy: Evaluating gestation-specific risks of fetal and infant mortality’. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1998;105(2):169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471–0528.1998.tb10047.x. | |

Muglu J, Rather H, Arroyo-Manzano, et al. Risks of stillbirth and neonatal death with advancing gestation at term: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of 15 million pregnancies. PLOS Medicine 2019;16(7): e1002838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002838. | |

Keulen JK. ‘Induction of labour at 41 weeks versus expectant management until 42 weeks (INDEX): Multicentre, randomised non-inferiority trial’. BMJ (Online) 2019;364:1–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l344. | |

Mya KS, et al. ‘Management of pregnancy at and beyond 41 completed weeks of gestation in low-risk women: A secondary analysis of two WHO multi-country surveys on maternal and newborn health’. Reproductive Health 2017;14(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12978–017–0394–2. | |

Sotiriadis A, et al. ‘Maternal and perinatal outcomes after elective induction of labor at 39 weeks in uncomplicated singleton pregnancy: a meta-analysis’. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2019;53(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/uog.20140. | |

Keulen JKJ, et al. Induction of labour at 41 weeks versus expectant management until 42 weeks (INDEX): multicentre, randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2019;364:l344 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l344. | |

Grobman WA. ‘Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women’. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;379(6):513–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800566. | |

Hersh AR. ‘Induction of labor at 39 weeks of gestation versus expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women: a cost-effectiveness analysis’. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Elsevier Inc., 2019;220(6):590.e1–590.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.017. | |

Boulvain M. ‘Membrane sweeping for induction of labour (Review)’. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):1–89. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000451.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com. | |

Avdiyovski H. ‘Membrane sweeping at term to promote spontaneous labour and reduce the likelihood of a formal induction of labour for postmaturity: a systematic review and meta-analysis’. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;39(1):54–62. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30284490. | |

Wennerholm U-B, et al. Induction of labour at 41 weeks versus expectant management and induction of labour at 42 weeks (SWEdish Post-term Induction Study, SWEPIS): multicentre, open-label, randomised, superiority trial. BMJ 2019;367:l6131 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6131. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)