This chapter should be cited as follows:

Vieira-Baptista P, Ventolini G, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419933

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 12

Infections in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Francesco De Seta, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, University of Trieste, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

Dr Pedro Vieira Baptista, Lower Genital Tract Unit, Centro Hospitalar de São João and Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Chapter

Other Forms of Vaginitis (Aerobic Vaginitis/Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis, Cytolytic Vaginosis, Leptothrix)

First published: July 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

In most papers and textbooks, it is still considered that “vaginitis” are limited to candidiasis or candidosis, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and trichomoniasis. Not surprisingly, some studies report a rate of “unspecific vaginitis” that can be as high as 30%.1 This high rate derives from both insufficient diagnostic workup, but also from the non-acknowledgment of other entities, such as aerobic vaginitis/desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (AV/DIV) and cytolytic vaginosis (CV). These remain controversial and are not universally accepted.2 Nevertheless, they need to be discussed and listed among possible cases of vaginitis; this will foster investigation and publication on the topic.

AEROBIC VAGINITIS/DESQUAMATIVE INFLAMMATORY VAGINITIS

A short history of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis and aerobic vaginitis

The first case report of DIV we are aware of comes from Germany, in 1954. Franken and Rotter described a case of “colpitis serofibrinosa” of unknown origin, in a 12-year-old girl, who was cured with local estrogen.3

In 1956, Scheffey et al. in the United States recommended local hydrocortisone for an “exudative vaginitis” in a 50-year-old woman.4

Gray and Barnes, in 1965 introduced the term “desquamative inflammatory vaginitis”, reporting on 478 women with vaginal complaints; out of these, six premenopausal women were diagnosed with DIV.5

Gardner, in 1968, described and characterized eight cases out of 3,000 patients within a 15-year period as having DIV; he did not consider it an infectious condition and also recommended the use of vaginal hydrocortisone. The improvement with this approach was limited; vaginal estrogens were mostly ineffective. Gardner later considered that the condition was probably more common than previously suspected.6

In a retrospective case series, published in 1994, Sobel reported a series of 51 patients with DIV.7

In an overview of the topic, Oates and Rowen, from the United Kingdom suggested that DIV could be associated with lichen planus and that the cultured bacteria (streptococci and Escherichia coli, among others) could be merely unimportant bystanders.8 Later, DIV was referred to as “lichen planus in disguise”.9

Murphy, in 2004, considered that DIV could not be a condition itself, but rather a presentation of different blistering disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris, lichen planus and mucous membrane pemphigoid.10

Donders et al. (2002), in Belgium, defined aerobic vaginitis (AV) as an inflammation of the vagina in which aerobic bacteria predominate, in contrast with BV. Its specific interleukin (IL) signature is characterized by an increased level of IL-6, IL-1ß and leukemia-inhibitory factor in the vaginal fluid. They considered DIV as the “tip of the iceberg”, corresponding to the most severe forms of AV. A score for the diagnosis, as well as for grading of the severity of AV, based on phase contrast wet mount microscopy (WMM) was proposed.11

AV and DIV prevalence and characteristics

Patients with AV and DIV may suffer for months or even years, until the correct diagnosis is established by a specialist.

According to most reports, the prevalence of AV ranges between 7 and 12%.12 During pregnancy it has been reported within a similar range (8–11%).11,13,14,15

In women with vulvovaginal complaints the rate may be higher (5–24%).11,14,16 Fan et al., in China, reported a rate of AV of 23.7% (156/657) among symptomatic women.17 Zhang et al. diagnosed 186 women with AV and an additional 98 with mixed infections including AV, but did not mention the total number of investigated women with discharge or complaints.18 They used the scoring system proposed by Donders et al. or the Tempera criteria (abnormal yellow discharge; foul smell, but negative whiff test; pH >5; abundant vaginal leukocytes).19 The inclusion criteria were as follows: being sexually active, age 19–50 years, Han ethnicity, diagnosis of AV either isolated or in context of a “mixed infection”. They considered a “mixed infection” if AV was encountered along with one or several of the following conditions: BV, vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomoniasis or CV.

The data on DIV prevalence are scarce worldwide. In the last decades only a few series have been reported. Sobel et al. reported 130 cases of DIV in 3,000 patients with vulvovaginal complaints (4.3%), during a 12-year period. Their mean age was 48.6 years, with half of them being postmenopausal.20

According to the personal experience of one of the authors, in the German Center for Infections in Gynecology and Obstetrics, which exists since 2012 in Wuppertal, DIV was diagnosed in 71 women, out of more than 4,000 patients with vulvar and/or vaginal complaints. In 16 cases biopsies were performed: one resulted in a diagnosis of vaginal adenosis and five in plasma cell vaginitis.21

Donders et al. described AV, encompassing severe AV/DIV in 50 of 631 (7.9%) patients.22

Bradford and Fischer, in 2010, reported on 101 retrospectively audited cases of DIV from their practice in Sydney, but did not mention the period elapsed. Half of the women were premenopausal (age range 18–83 years); 54% had ecchymotic lower vaginitis, 35% confluent vaginitis, and 8% only upper vaginitis.23

Risk factors for AV/DIV

Only a few studies addressed possible trigger factors for DIV. In the Wayne State University Vaginitis Clinic, a comparison between 47 women with DIV and a control group of 1,432 women was performed. Pain and vaginal complaints were reported in the DIV group in three quarters of the cases. Women with DIV were more likely to report a history of vulvovaginal candidiasis (odds ratio [OR] 4.4), BV (OR 25.5), pelvic inflammatory disease (OR 16.9), use of oral contraceptives (OR 4.9), menopause hormone therapy (OR 4.7) and having had a laparoscopic procedure (OR 22.2).24

In a retrospective evaluation of 101 women with DIV, in 56% trigger factors were identified, being diarrhea (16%) and prolonged high-dose intravenous antibiotics (15%) the most common ones. Immunosuppressive therapies were reported by only 3%.23

Autoimmune diseases occur when a genetically-susceptible individual encounters an environmental trigger (epigenetics) that induces autoimmunity via biochemical modifications, such as acetylation, methylation or other mechanisms.25

Van der Meijden and Ewing described 18 cases of a “papular colpitis”, which fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of DIV. The authors concluded, that it seemed to be an autoimmune-related condition, which responded to vaginal 10% hydrocortisone acetate with some success, despite commonly recurring.26

One of the first reports of a possible association between DIV and autoimmune disease described four cases of concomitant DIV and Crohn’s disease, but the authors focused on vitamin D deficiency in these patients; vitamin D supplementation resolved the symptoms of DIV.27

A rare cofactor for DIV may be toxic shock syndrome (TSS), which was considered a possible trigger in four cases, reported in two publications.28,29

TSS can occur in children, men and women, but is more common in menstruating women (probably due to the air entrapment in tampons). It is due to the production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1), in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. The toxin is more often produced by Staphylococcus aureus (only 1% of them are able to produce it); some Streptococcus pyogenes also have that capability. By the age of 14 years, about 80% of people have produced such antibodies and thus are not at risk of TSS. The TSST-1 is a superantigen, which can initiate a cascade of activated T-lymphocytes with a “cytokine storm”, which may lead to a multi-organ failure.30

Despite the decades-long suspicion of an immunological origin or at least a coincidence between DIV and autoimmune disorders, it was not until 2020 that the first reports were published. One of the earlier reports was on four cases of DIV in women with rheumatoid arthritis, three of which were being treated with rituximab. A causal relationship between rituximab and DIV could not be established, but one later report suggested it may be mediated by B-cell depletion.31,32 Rituximab is also acknowledged as a rare trigger for ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum of the vulva.33,34 Four more cases of DIV and Crohn’s disease and one of lupus were published by the same group.31,35 In the latter, DIV was treated with vaginal 2% clindamycin and 10% hydrocortisone, with partial improvement. Of note, once lupus treatment with daily oral 20 mg prednisone was started during pregnancy, the woman experienced complete remission of DIV. The remission, however, was not sustained and long-term oral corticosteroids were needed.

Sobel et al. reported a history of thyroid disease in 23% of their cases, nevertheless, Hashimoto’s disease was not mentioned.20

Song et al., in a series of 33 women with DIV, reported that one third had “immune dysfunctions”, including five cases of thyroid disease, two on systemic corticosteroids, and one each of ulcerative colitis, common variable immunodeficiency, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s disease, Raynaud’s disease, disseminated sarcoidosis, and undifferentiated connective tissue disorder.36

The clinical evident vaginal inflammation of AV/DIV correlates with significantly elevated vaginal IL-1 and -6 in comparison to healthy vaginas, also in pregnant women.22 Vaginal AV samples show only slightly increased levels of toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 and a reduction of TLR-2 and -6. Both receptors are responsible for two pathways central to mucosal immunity. This led Oerlemans et al. to conclude that the bacterial profile of AV may be merely a consequence of the inflammatory conditions and/or altered hormonal regulation, rather than the opposite.37

Microbiology

Donders et al. (2002) and other investigators, using cultures, identified predominantly group B-streptococci (GBS), S. aureus and E. coli, but also Gardnerella spp., in women with DIV.7,22,38,39

In an Australian case series, cultures resulted in pure growth of bacteria in 20% of cases: 13% Streptococcus agalactiae, 2% S. aureus, one case of coliform bacteria, two cases of Candida albicans and two cases of non-albicans Candida spp..23

In North Ethiopia, in a study on 422 pregnant women, 20.1% had BV and 8.1% AV. The isolated bacterial strains in AV patients, by culture, were in 38.6% coagulase-negative staphylococci and in 29.5% of cases S. aureus.40

A prospective study carried out in Vietnam and including 323 pregnant women, showed a 15.5% rate of AV (light in 84% and moderate in 16%). Vaginal cultures revealed S. agalactiae in 6%, Enterococcus spp. in 4%, S. aureus in 4%, and Acinetobacter baumannii in 2% of cases.41

Non-cultural modern techniques, like nuclear acid amplification tests (NAATs), 16S rRNA gene sequencing and others, are a new approach used to characterize the vaginal microbiota. Using this approach, one study showed a significantly different microbiota in 10 patients with AV when compared to healthy controls, with a dominance of highly cytotoxic mutant S. anginosus. The bacterial clusters between AV and BV were different, but closer to each other than each AV or BV to healthy vaginas.42

A further study with 20 patients with AV in comparison to 19 with BV and a healthy control group of 18 women provided a deeper insight into the microbial communities and the vaginal immunological inflammatory factors. Women with AV had reduced absolute abundances of bacteria in general, especially lactobacilli. Nevertheless, Lactobacillus spp. remained the dominant taxon in 25% of the AV samples, while the others showed high relative abundances of S. agalactiae (and S. anginosus); Gardnerella spp. and Prevotella bivia were identified in >50% of the cases. Lactobacillus gasseri was the predominant lactobacilli species in four out of five cases of AV, in contrast to BV and controls.37

Clinical signs and symptoms

Patients with moderate to severe AV or DIV may present with yellow-green, often copious, discharge for weeks or months. Typically, they have been treated without success with different vaginal antifungals, probiotics, antibiotics and/or antiseptics. If vaginal clindamycin was prescribed, they may report transient less discharge during the duration of the treatment.

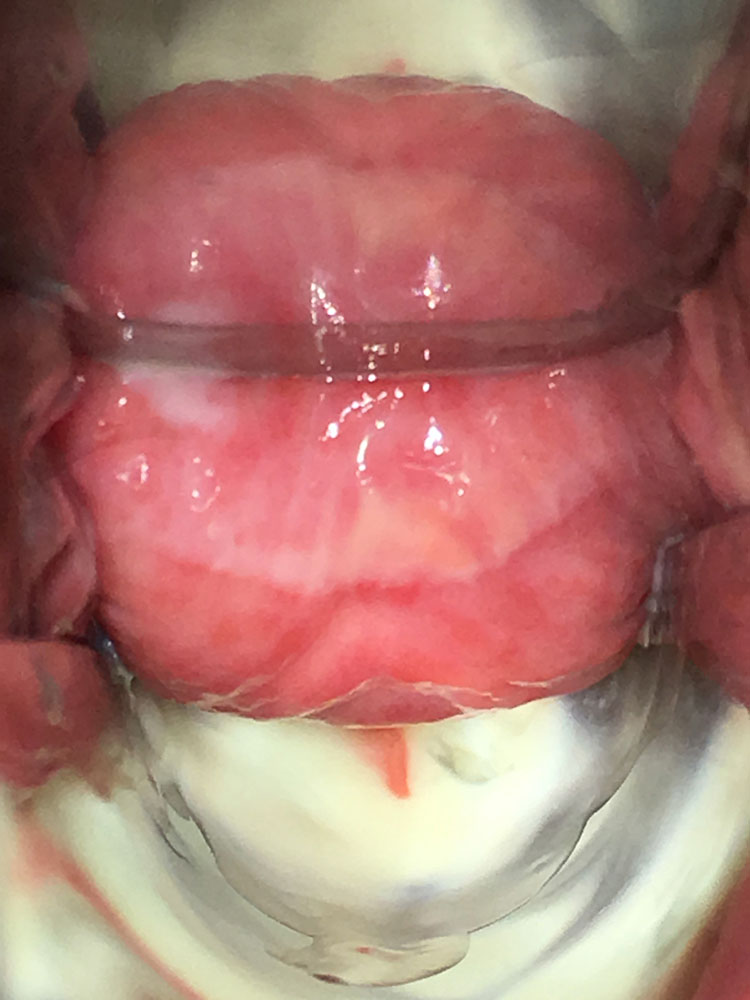

The vaginal pH is increased (higher than 5 and sometimes as high as 7–8). The foul smell often noted in BV is typically absent. There may be a more or less severe vaginitis, sometimes garland-like/tortuous (Figures 1 and 2); in more severe cases, desquamation and bleeding of the upper third of the vagina, including the surface of the cervix may be evident (Figure 3). The vestibule may also be inflamed (Figure 4).

1

Aspect of the vaginal mucosa in a woman with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Presence of inflammation/enanthema and copious discharge.

2

Aspect of the vaginal mucosa in a woman with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Petechiae of the vaginal mucosa and copious discharge.

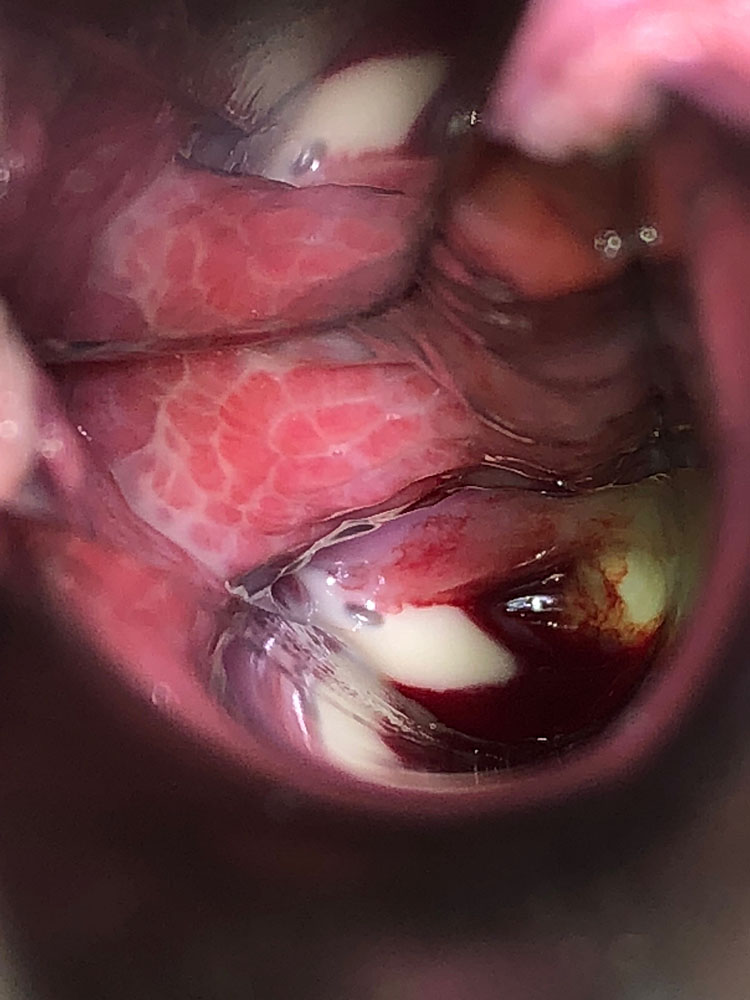

3

Involvement of the cervix in a woman with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

4

Erythema of the vestibule associated with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

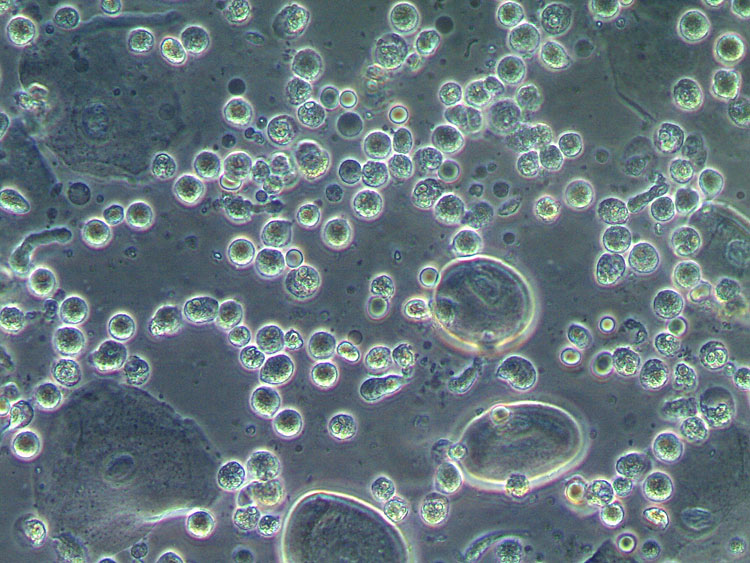

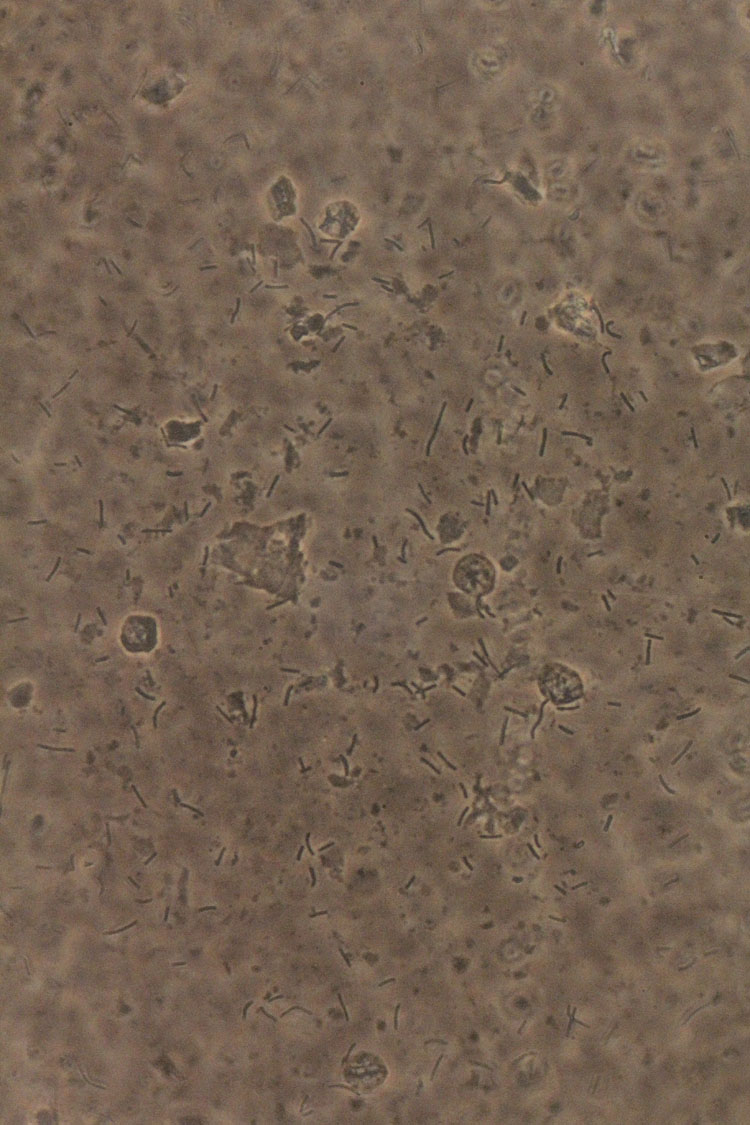

The microscopic wet mount examination (400×), preferably using phase contrast, will show many activated “toxic” leukocytes, no clue cells, absent lactobacilli, and dominance by a coccoid microbiota (sometimes in chains). Parabasal cells of the deep layers of the vaginal wall are typically identified, also in premenopausal women (Figure 5).43

5

Wet mount microscopy (400×, phase contrast). Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: lactobacilli absent, presence of cocci, severe inflammation with predominance of toxic leukocytes, presence of parabasal cells.

AV/DIV and pregnancy

A recent review that included 97 studies with focus on AV evaluated the possible influence of GBS, E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis and Klebsiella pneumoniae on pregnancy outcomes. These bacteria, which are predominant in AV, can produce different toxins, which influence the local immunity. There is no definite evidence, that any of the above-mentioned bacteria alone is responsible for preterm birth or other adverse pregnancy outcomes, but associations between the two have been published.44

There is no strong evidence for early miscarriage in women with AV, but AV during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy is related to increased risk of chorioamnionitis and funisitis.45

AV in the third trimester has been associated with an increased risk of puerperal sepsis (OR 8.65, p = 0.02) and an elevated risk of neonatal infections. There was no increased risk for preterm birth.41 On the other hand, in another prospective study, including 100 women with and 500 women without AV, an increased risk of preterm birth and prelabor rupture of membranes was shown (OR 3.06 and 6.17, respectively). AV was associated with a 2.19-fold higher risk of admission of the neonate into an intensive care unit.46

AV and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

It has been suggested that the bacterial and/or immunological changes in the vagina of women with AV may promote cervical dysplasia.47,48,49 In a prospective study including 110 consecutive women with abnormal cervical cytology and 118 normal controls, the authors found a significant correlation between having an abnormal cytology and the presence of abnormal vaginal microbiota (50% vs. 31.4%, p = 0.004), and moderate to severe AV (msAV) (13.6% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.049). In another study the most important risk factors for CIN2+ were smoking (OR 3.04) and msAV (OR 3.18). BV was found significantly more often in CIN1 patients (8/31 = 25.8%).50

In another larger series it was found that moderate or severe vaginal inflammation were more common in women with major cervical cytology abnormalities (41.0% vs. 28.8%, p = 0.04). The same was true for msAV (16.9% vs. 7.2%, p = 0.009) as well as when dysbiosis (encompassing msAV and BV) was considered (37.3% vs. 20.0%, p = 0.001). No associations could be established between BV and major cytological abnormalities. Also, no association was found between deviations of the vaginal milieu and high-risk HPV infection.51

Chronic inflammation by hyperexpression of cytokines, reduced abundance of lactobacilli, and presence of bacteria of the genus Sneathia spp. and Delftia spp. in a vaginal community state type IV (in which AV/DIV fits) or III have a strong association with cervical dysplasia progression.52

AV/DIV and sexually transmitted infections

A dysbiotic vaginal microbiome, as well as vaginal inflammation, is known as a risk factor for the acquisition of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The studies on STIs and AV/DIV, apart from those correlating it with HPV infection, are scarce. There are estimations of a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk for trichomoniasis, chlamydial or gonococcal infections in women with an intermediate (which is typical for AV/DIV) or a higher Nugent score.53

One study has associated AV with a higher risk of infection by Chlamydia trachomatis.54

Histology

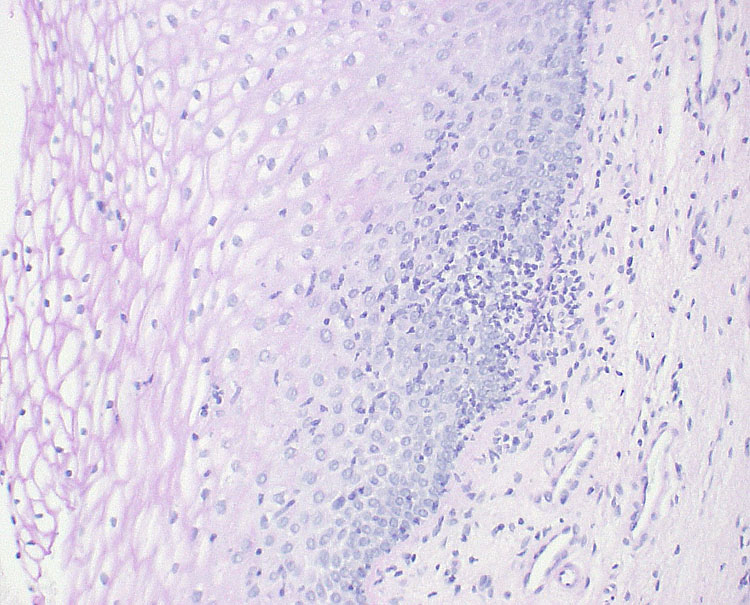

Biopsies are not recommended for the diagnosis of AV/DIV. If performed, the results are usually disappointingly non-specific findings of “light vaginitis” (Figure 6). Sometimes, a lichenoid or non-specific mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly lymphocytic may be described.26,55 A detailed list of histopathologic findings in 36 women with DIV, during a 10-year time frame, revealed a lymphocytic infiltrate in 17% (moderate to heavy in 83%), secondary infiltrate with plasma cells in 20%, epithelial hemorrhage in 33%, stromal hemorrhage in 25%, and vascular congestion in 50%.36

6

Biopsy of the vaginal mucosa of a woman with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (hematoxylin and eosin, 1000×), showing light inflammation.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis should be performed with a combination of the patient’s history, clinical signs, and WMM (400×, ideally using phase contrast) (Figure 5). The use of staining is not considered necessary for the diagnosis of AV/DIV. For further details on how to perform and interpret WMM we recommend the reading of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) recommendations.43

Microbiological cultures are not recommended, as it does not distinguish a possible infection from colonization and is not useful guiding the treatment.

Donders et al. introduced a score, based on WMM, which allows to classify AV into absent, light, moderate or severe (DIV) (Table 1).22

1

Aerobic vaginitis score, after Donders et al..22

Score | Lactobacillary grade | Number of leucocytes | Proportion of toxic leucocytes | Background microbiota | Proportion of parabasal cells |

0 | I and IIa | ≤10/hpf | None or sporadic | Unremarkable or cytolysis | <1% |

1 | IIb | >10/hpf and ≤10/EC | ≤50% of total leucocytes | Small coliform bacteria | 1–10% |

2 | III | >10/EC | >50% of total leucocytes | Cocci or chains of cocci | >10% |

A score <3 corresponds to “no AV”, score 3–4 to “light AV”, score 5–6 to “moderate AV”, and scores >6 to “severe AV” or DIV

hpf, high power field; EC, epithelial cell.

A recent Chinese study compared clinical features of AV using WMM (400×) or Gram stain (1000×). There were no significant differences, except that in the latter the distinction between toxic and non-toxic leukocytes was not feasible. The authors proposed therefore a new score based on Gram stain, similar to the WMM based one, but without considering the parameter “toxic leukocytes” and including an additional scoring for clinical manifestations (score 0 – pH <4.5 and no clinical signs; score 1 – pH >4.5 or at least one abnormal sign; score 2 – pH >4.5 and at least one abnormal sign; the clinical signs are hyperemia or yellow discharge).56

The qPCR kit Bacterial Vaginosis Real-TM Quant (Sacace Biotechnologies, Como, Italy) is a promising tool for the distinction between BV and AV/DIV.57

Differential diagnosis

The list of possible differential diagnosis includes the following:

- BV, which is distinguished from AV/DIV by the absence of inflammation, presence of clue cells in WMM and, usually, a positive whiff test (Table 2);

- Postmenopausal (or lactating) atrophic vaginitis, which can be suggested by the patient’s history and responds well to estrogens;

- Trichomoniasis, which should always be excluded in severe cases using a nucleic acid amplification test if no trichomonads are identified in the WMM preparation;

- Streptococcus pyogenes/group A streptococcal (GAS) vulvovaginitis, according to the patient’s history and cultures;58

- Chemical or allergic vaginitis (rare);

- Vaginal lichen planus, excluded by the patient’s history, clinical signs and, in some cases, by biopsy;59

- Toxic shock syndrome associated with vaginal/mucous membrane inflammation;

- Immunobullous diseases (very rare in the vagina); the diagnosis is usually established by biopsy and immunofluorescence.

The clinical and microbiological characteristics of AV/DIV in contrast to BV are summarized in Table 2.

2

Characteristics of AV and BV.

AV/DIV | BV | |

pH | >4.5 (often 6–7) | >4.5 |

Discharge | Yellowish, fluid | Gray-white, creamy |

Whiff test | Negative | Positive |

Microscopy

|

|

|

Microbiota | S. agalactiae, S. anginosus, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. aureus, other | Gardnerella spp., Fannyhessea (Atopobium) vaginae, BVAB2, Megasphaera spp., other |

CST | IV | III, IV |

Inflammatory cytokines | Increased | Moderately increased |

Treatment | Clindamycin Dequalinium chloride Vaginal estrogens Vaginal corticosteroids | Clindamycin Metronidazole Dequalinium chloride |

AV/DIV, aerobic vaginitis/desquamative inflammatory vaginitis; BV, bacterial vaginosis; BVAB 2, bacterial vaginosis associated bacteria 2; CST, community state type.

Treatment

DIV

There are no validated or widely accepted therapeutic schemes for AV/DIV. Vaginal hydrocortisone was suggested for the treatment of DIV in 1956, and has been used ever since.4 Later, the use of clindamycin was proposed because of its anti-inflammatory and cytokine-inhibiting properties.7 Some opt to use the ultrapotent corticosteroid clobetasol in a special vaginal formulation. As parabasal cells are often present in the vaginal wet mount, the use of vaginal estrogens is often recommended, but there is no evidence of better results.

In a retrospective study, involving 130 cases collected between 1996 and 2007, out of which data were available for 98 patients (mean age of 48.6 years; 50% postmenopausal), 54% were treated with clindamycin and 45% with hydrocortisone. Relief of symptoms within three weeks was experienced by 86%. The median time to discontinue the treatment was eight weeks. Around one third relapsed within six weeks and 43.4% within 26 weeks; cure at one year was noted only in 26%.20

Sobel and Reichman (2014) compared 2% vaginal clindamycin and vaginal 5% hydrocortisone for the treatment of DIV. The results were equal, but maintenance therapy was often necessary.60

AV

There are several, non-evidence-based treatments proposed for AV. Donders et al. in their seminal paper on AV did not suggest treatment recommendations and later stated, that “the best approach for treating AV in both pregnant and non-pregnant women is unknown”.11,22

The most often mentioned treatments for moderate forms of AV include 2% vaginal clindamycin cream, kanamycin and moxifloxacin, often combined with vaginal estriol or estradiol and/or, in more severe cases, vaginal corticosteroids.12,17,19,22,61

Data on antiseptics and probiotics are lacking, especially during pregnancy.62

One study mentioned a vaginal soft gel product containing silver ions for 7 days with acceptable success in 59.2% (19/32) of cases.63,64

The recommended treatments for DIV are summarized in Table 3.

3

Treatment options for desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (adapted from Paavonen and Brunham 2018).61

Treatment | Regimen |

Recommended treatments | |

Clindamycin 2% cream | Intravaginally daily at bedtime for 1–3 weeks Consider maintenance therapy once or twice a week for 2–6 months |

Topical glucocorticoid | |

Hydrocortisone 300–500 mg | Intravaginally daily at bedtime for 3 weeks Consider maintenance therapy once or twice a week for 2–6 months |

Clobetasol propionate 0.05% | Intravaginally daily at bedtime for 1 week, duration not evidence-based |

Additional recommended treatments | |

Fluconazole | 150 mg orally once a week as maintenance therapy (in woman at risk of candidiasis) |

Topical vaginal estrogen | Twice a week |

Attempt at synthesis

The anamnestic hints, the presence of toxic leukocytes in AV/DIV, the vaginal proinflammatory cytokines’ profile and the failure of isolated antibiotic treatments are strong arguments for a relationship with immune disorders. Autoimmune diseases evolve by many different factors, not yet fully understood but encompassing individual factor/genes, intrauterine transferred influences, environmental factors/epigenetics, hormonal influences, and gut microbiome interactions.

Neither the individual healthy vaginal ecosystem, composed of tissue factors in permanent interaction with the microbiome, hormones and the immune system, nor AV/DIV are equal in terms of cause or presentation in every individual. Theoretically, it can be assumed, that light and moderate AV represent part of a continuum that in its extreme forms corresponds to severe AV or DIV. Therefore, we can speculate that, in the future, the management of these conditions will be individualized, possibly including manipulation of the peripheral immune system.

It remains unconfirmed, albeit possible, if some mutant bacterial species or strains, specially of GBS or S. anginosus with cytotoxic potential, play a relevant role in the development of AV/DIV. Nevertheless, such bacteria are often transient colonizers of the healthy vagina. Why would they become the origin of these disorders? Current understanding is that they are secondary “freeloaders” in a disturbed vaginal environment.

It is therefore not logical to primarily treat AV/DIV with antibiotics or antiseptics. Probiotics, including lactobacilli may also not be helpful, because the changed vaginal environment is no fertile ground for their growth.65 Interdisciplinary basic research and prospective multicentric therapy trials are urgently necessary to mitigate the lack of evidence.

The designation “desquamative inflammatory vaginitis” is historically established, but is uncomfortably bulky, and desquamation is usually only seen in severe cases, associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment. “Aerobic vaginitis” misleads to expect an infectious origin, which very probably is not the case. A new designation, highlighting the inflammatory nature of this form of vaginitis may be useful to avoid these pitfalls.

CYTOLYTIC VAGINOSIS

CV is characterized by an increased number of lactobacilli of different sizes, along with cytolysis of the intermediate cells of the vaginal epithelium, evident by the presence of bare nuclei and cytoplasmatic debris. Typically, other bacteria and inflammation are absent. Some authors consider the presence of Candida spp. as an exclusion criterion for the diagnosis,43 but according to the authors' experience, in clinical practice the coexistence of both is not a rare event. The symptoms of both conditions are similar and, in practice, most of the women with CV are misdiagnosed with recurrent or chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis, despite negative cultures and lack of response to antifungal treatment.

Since the seminal work of Albert Döderlein, it has been widely accepted that lactobacilli have a protective role in the female genital tract.66,67 The fact that an increased number of lactobacilli may lead to symptoms in some women poses a challenge to the traditional point of view that vaginal lactobacilli can never be deleterious or too many. This, associated with lack of objective diagnostic criteria and the limited number of studies published, leads some authors not to accept this entity.2

Nevertheless, we believe there are some data, despite the limited quantity and quality, that makes it worthwhile to discuss the condition, rather than ignoring it.68 Hopefully, the discussion on the topic will clarify if CV should be listed along the causes of vaginitis or not.

Historical perspective

Despite previous descriptions of the condition in the literature, Cibley et al. get the credit for coining the term CV to designate it, in 1991.69 However, the authors mostly describe their experience, the clinical presentation and suggest diagnostic criteria, as well as treatment approaches, but scientific rigor behind this paper is considered insufficient by some.2 The topic has been rarely discussed in the literature ever since, not only but also due to a publication bias: reviewers and editors are likely to consider that CV does not exist, reducing the chance of publication. Recently, in 2021 and 2023, the ISSVD listed CV among the conditions that can be diagnosed using WMM.43,70

Etiology

The etiology of CV remains ununderstood. There is a possible role for sexual steroids, as the condition is not usually seen in women in hypoestrogenic states, and it is apparently more common in phases of absolute or relative increased progesterone (luteal phase, pregnancy, perimenopause).1 In one study, a high rate of CV was found in women being submitted to fertility treatments, pointing to a possible role of hormone treatments.71

While intuitive, the initial theory that an excessive amount of lactobacilli and consequent increase in lactic acid leads to vaginal epithelial cell damage and vulvar burning remains unconfirmed.69 One study by Beghini et al. showed that, as expected, the levels of vaginal lactic acid are increased in women with CV. More surprisingly, it was shown that in CV there is a disproportion between the levels of the D- and L-isomers of lactic acid, favoring the L-isomer. Lactobacillus crispatus and L. gasseri produce the isomer D- and L-; L. jensenii produces only the D-isomer. L. iners and the vaginal epithelial cells produce only the L-isomer.72,73 This may lead to the speculation that either a specific species of lactobacilli is involved or that the cause of this isomer’s imbalance is due to excessive production of L-acetic acid by the vaginal epithelial cells. This imbalance can lead to alteration of the expression of the extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer and consequent cell necrosis, with release of glycogen to the vagina, making it available to lactobacilli.74

Yang et al. in 2021 showed that, in women with CV, dominance by L. crispatus was more common than in healthy controls (88.7% vs. 56.4%, p < 0.01) and also that the isolation of more than two species of lactobacilli was rare in affected women (1.3% vs. 12.2% in healthy controls, p = 0.013).75 The dominance of L. crispatus had already been previously described.76

The previous use of antifungals is sometimes listed as being possibly associated with CV. However, given that most of these women are usually misdiagnosed with candidiasis and treated with antifungals precludes any conclusion.1

Prevalence and epidemiology

Given the uncertainties surrounding CV, including the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria, it is not surprising that its true prevalence is unknown. The few available studies lead to an estimation of <7% in symptomatic women.68 CV is rarely seen out of the reproductive years.68,69,75,77,78,79,80,81 The prevalence rate may vary according the diagnostic technique, with Pap test yielding lower rates than WMM.68

In one study on women undergoing fertility treatments, a very high rate of CV was reported (20.7%).71

There are no data on ethnical or geographical variation of prevalence.

Risk factors

The data on risk factors for CV are scarce and of poor quality. One study suggested that CV was more common in women who have intercourse less frequently, but significant biases may have been induced (i.e. in this study the comparison group was composed by women who engaged in commercial sex).82

According to our experience, the finding of a cytolytic pattern is very common in pregnancy, however it is extremely rare that these women are symptomatic. We have seen cases of symptomatic women that get asymptomatic during pregnancy.

Complications

A case-control study showed an association between CV and localized provoked vulvodynia (vestibulodynia), but no conclusions on its nature could be drawn (i.e. the metabolites of the increased number of lactobacilli lead to vulvodynia or women with vulvodynia have less intercourse and thus are more likely to have this type of microbiota).83 These results do not seem to be supported by the research concerning vaginal microbiome and vulvodynia.84,85,86,87

In one study in women undergoing fertility treatments and in which the vaginal microbiota was evaluated using WMM, no positive or negative impact of CV was noted.51

The concept that vaginal lactobacilli confer health benefits remains unchallenged. In fact, one study suggested that women with CV were less likely to be diagnosed with cervical high-grade intraepithelial epithelial lesions.88 Nevertheless, in another study no relation between CV and Pap test abnormalities or HPV infection could be established.51

Women are often concerned that the chronicity of symptoms and the lack of response to previous treatments may translate a severe condition, associated with complications such as infertility and cancer. The current data allows us to reassure them that there seems to be no long-term risks.

Signs and symptoms

The percentage of women with a cytolytic pattern that are symptomatic is unknown.

The presentation of CV is very similar to that of vulvovaginal candidiasis.81 Women usually refer to vulvar burning (more often than itching). According to our experience, the symptoms tend to be absent or mild when the woman wakes up and develop after getting up. In women not using hormonal contraceptives, the symptoms usually begin with the ovulation, worsening until the onset of the menses. During the menses the symptoms tend to abate. Some women also will describe terminal/postmictional dysuria and dryness/dyspareunia.1,69,78,80,89

The vulvar exam is usually unremarkable, but sometimes a discrete erythema may be present. The typical vaginal discharge is usually white, thick and lumpy, sometimes described as having an acidic or vinegar smell.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on a typical clinical history, the vulvovaginal exam, pH measurement, microscopy, and Candida spp. cultures. The whiff test is negative in women with CV.

The first two points have already been described in the previous sections. The vaginal pH is typically low in women with CV; some studies refer to a cut-off of 4.2, while others consider that it is ≤3.8.69,76,80 The pH can be measured using a pH strip, either directly from the vaginal walls (avoiding the cervix and the posterior fornix), from a sample collected from a glass slide for microscopy, or from the speculum blades (if lubricant was not used).90 The pH measurement is only useful if there was no recent vaginal bleeding, medication, or intercourse.

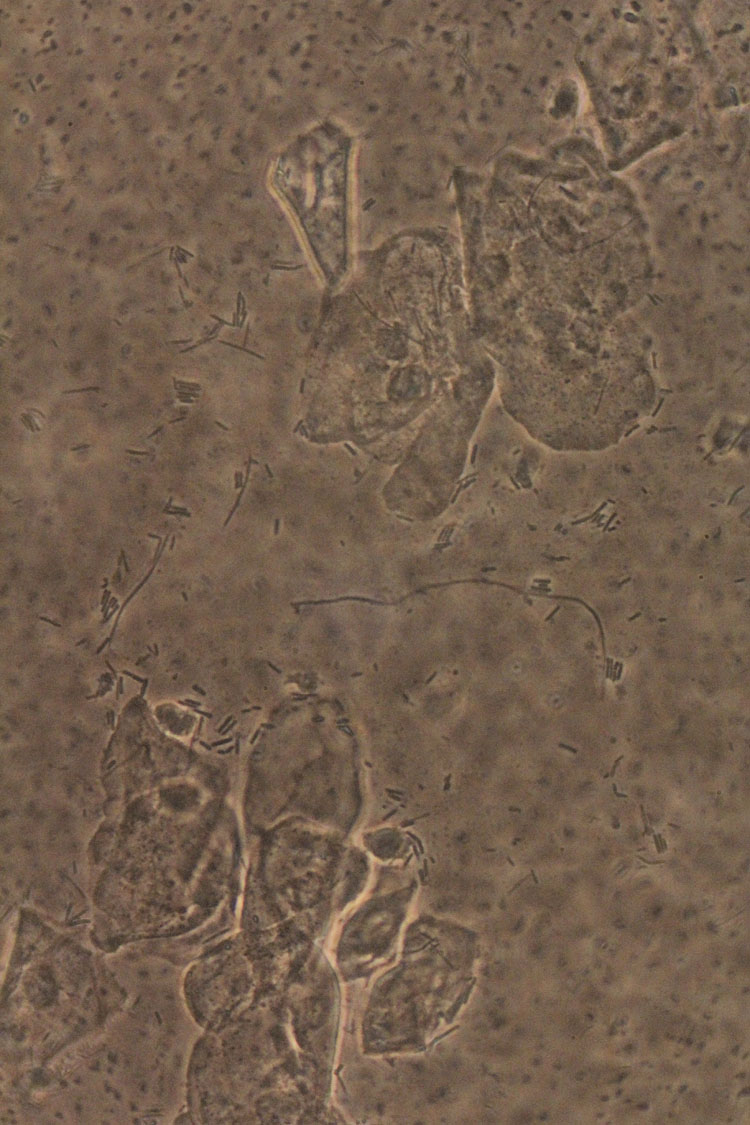

The most important exam for the diagnosis is WMM, which is the gold standard for the diagnosis (Figure 7). According to the ISSVD recommendations, we prefer to always use phase contrast microscopy, despite the lack of evidence that it increases the performance for CV.43 In one study on asymptomatic women, it was suggested that the sensitivity of WMM for a cytolytic pattern may be increased if sampling is performed from the anterior fornix; it is unclear if that finding is significant in symptomatic women.91 In terms of clinical practice, we sample from one of the lateral walls, avoiding the cervix and the posterior fornix.

7

Wet mount microscopy (400×, phase contrast). Cytolytic vaginosis: abundant lactobacilli, no other bacterial morphotypes present, inflammation absent, bare nuclei, and cytoplasmatic debris.

Ideally, the sample should be obtained when the woman is symptomatic, and without intercourse, vaginal medication, or bleeding in the previous 48–72 h.92 One option may be to schedule the appointment to a date as close as possible to the beginning of the menses or breakthrough bleeding. The sample can be read immediately or allowed to air dry and later rehydrated.43

The diagnosis is assumed when (1) there is an abundance of lactobacilli, usually with different lengths, (2) other bacterial morphotypes are scarce or absent, (3) leukocytes are absent or scarce, and (4) cellular debris are present (fragments of cytoplasm and bare nuclei).43 The pattern can easily be recognized with some training in microscopy. The finding of this typical pattern should not preclude the thorough examination of several fields, as other findings, such as fungal structures may also be present. Sometimes the absence of Candida is referred to as an exclusion criterion for the diagnosis of CV, but both conditions are sometimes seen coexisting in clinical practice – we suggest, if symptomatic, to start by treating candidiasis.

Of note, the diagnosis can also be established using the Pap test (probably more difficult when liquid-based cytology is used) or Gram stain.93

However, it must be highlighted that standardization of diagnostic criteria, as well as a scoring system, are urgently needed.

Cultures for Candida are recommended in all cases; other cultures, namely for bacteria, are not useful.

Currently, there are no molecular tests for the diagnosis of CV. Since the diagnosis implies the use of WMM, which is not performed by the majority of providers, most cases will be missed.94

Treatment

The recommendations for treatment are mostly empirical and/or based on small samples. Treatment is only recommended if the woman is symptomatic, and especially after the exclusion of other causes for her symptoms.

The most commonly recommended treatment option in the literature is sodium bicarbonate. It can be used as sitz baths or vaginal irrigations. The latter should only be prescribed following a microscopical confirmation of the diagnosis. While both options probably work by a buffer effect (raising the pH), irrigations seem to be associated with longer relief, likely due to the decrease in the vaginal bacterial load.

The recommended concentration of the sodium bicarbonate is 30–40 mg per liter of water. One option is to use it daily for 2 weeks and then on demand. The effect tends to be more substantial if the treatment is performed during the morning period. Keeping track of when the symptoms develop in a calendar may be a useful tool to predict when treatment will be needed.69 There is a huge variation in terms of duration of the symptoms; some women will need to resort to sodium bicarbonate for months or even years. Informing the women that the treatment is not curative, but rather allows the control of symptoms and that it may be needed for long periods may lead to a better acceptance.

The use of antibiotics (topical clindamycin or oral amoxycillin) is sometimes suggested, but data are scarce, and these should not ever be considered as first-line options. Changes in lifestyle, diet, or contraceptive options do not seem to be effective.1

Prognosis

We could not find any longitudinal study on women with CV. Our clinical impression is that a few women will improve rapidly with sodium bicarbonate treatment, the majority will have symptoms for a few months, and in a few it will last for years. The typical patients will notice a reduced need to use sodium bicarbonate over time, until they no longer need it. Also, according to our experience, even very symptomatic women get asymptomatic during pregnancy – and this fact may hold the key to explain this mysterious and controversial condition.

In the absence of menopause hormone therapy, CV is very rare in postmenopausal women.

LEPTOTHRIX

Introduction

Leptothrix are very long bacteria, not so commonly found in vaginal wet mount preparations. They seem to rarely cause symptoms; if symptomatic it is hard to discern from candidiasis.95 Some authors refer to this condition as lactobacillosis, while others use this concept for cases of an increased number of lactobacilli in the absence of cytolysis.43 In asymptomatic women, vaginal lactobacilli usually measure between 5 and 15 μm in length (Figure 8). Patients with leptothrix have long, segmented lactobacilli chains, ranging between 40 and 75 μm in length.96,97

8

Wet mount microscopy (400×, phase contrast). Leptothrix: presence of long lactobacilli (with normal lactobacilli in the background).

Prevalence

The prevalence of this condition is still unknown. In a recent study, involving 3,620 women, it was reported to be of 2.8% (2.4% in women with symptoms of vaginitis and 3.2% in general populations).95 In other studies it ranged between 0.5–15.2%.98,99

Origin

The origins of these long lactobacilli are of continuous debate ranging from a specific species or an ordinary lactobacillus species that obtains this bizarre morphology as a result of external factors, for instance, antibiotic or antifungal use.95

Associations

Leptothrix has been associated with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, vulvodynia, HIV, and abuse of over-the-counter antifungal medications.95,100,101 According to a recent publication, antibiotic and/or antifungal, which are commonly prescribed to treat vaginal infections, can put some pressure causing this phenomenon, which is common among bacteria. Additionally, an association with the use of probiotics has been suggested.95

Diagnosis

The gynecological exam is usually unremarkable. The diagnosis can easily be established using WMM, but these long lactobacilli can also be seen in stained slides (i.e. Pap or Gram) (Figure 8).43 Bacterial cultures are not helpful, but fungal ones can be helpful for the differential diagnosis with candidiasis. The pH is usually within normal range.95

Treatment

Treatment will be rarely needed; if the woman is symptomatic and another condition is present (i.e. candidiasis or BV), its treatment should be attempted first. Data on treatment results from observational studies and are of poor quality. One of the reported treatments in the literature for leptothrix consists of 500 mg of amoxicillin-clavulanate to be given orally every 8 h for seven days. Horowitz et al. reported that 86.3% of his patients became asymptomatic following this treatment. For patients that were penicillin allergic he reported prescribing 100 mg of doxycycline every 12 h for 10 days. The patients remained clinically and laboratory asymptomatic at their 18 months’ follow-up visit.96 Cepicky et al. published a series of cases of patients with lactobacillosis treated with vaginal nifuratel; they observed 22.2% of relapses after 1 month.102

Conclusions

Leptothrix is an infrequent finding, and it is event debatable if it ever produces vulvar symptoms. Leptothrix is certainly not a marker of dysbiosis. The treatment must be considered based on patient’s symptoms.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Wet mount microscopy should always be performed as part of the study of a woman with symptoms of vulvovaginitis.

- In the case of a suspected diagnosis of severe aerobic vaginitis/desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, trichomoniasis should always be excluded using a nucleic acid amplification test.

- Cultures are not helpful for the diagnosis of aerobic vaginitis/desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

- The treatment of aerobic vaginitis/desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is guided by the microscopy findings and can include topical antibiotics or antiseptics, corticosteroids and estrogens. In severe cases, treatment may be needed for several months.

- The treatment of cytolytic vaginosis consists of irrigations or sitz baths, using sodium bicarbonate.

- Cultures for Candida should always be performed in women with cytolytic vaginosis.

- Leptothrix is rarely symptomatic and treatment should only be prescribed in the absence of another explanation for the symptoms.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Vieira-Baptista P, Bornstein J. Candidiasis, Bacterial Vaginosis, Trichomoniasis and Other Vaginal Conditions Affecting the Vulva. In: Vulvar Disease: Breaking the Myths, Bornstein J. (ed.) Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019:167–205. | |

Voytik M, Nyirjesy P. Cytolytic Vaginosis: a Critical Appraisal of a Controversial Condition. Current Infectious Disease Reports 2020;22(10):26. | |

Franken H, Rotter W. [So-called vaginal hydrorrhea (colpitis sero-fibrinosa allergica dysregulativa)]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1954;14(2):154–62. | |

Scheffey LC, Rakoff AE, Lang WR. An unusual case of exudative vaginitis (hydrorrhea vaginalis) treated with local hydrocortisone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1956;72(1):208–11. | |

Gray LA, Barnes ML. Vaginitis in women, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1965;92:125–36. | |

Gardner HL. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: a newly defined entity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1968;102(8):1102–5. | |

Sobel JD. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: a new subgroup of purulent vaginitis responsive to topical 2% clindamycin therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171(5):1215–20. | |

Oates JK, Rowen D. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. A review. Genitourin Med 1990;66(4):275–9. | |

Edwards L, Friedrich EG Jr. Desquamative vaginitis: lichen planus in disguise. Obstet Gynecol 1988;71(6 Pt 1):832–6. | |

Murphy R. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Dermatol Ther 2004;17(1):47–9. | |

Donders G, Bellen G, Rezeberga D. Aerobic vaginitis in pregnancy. Bjog 2011;118(10):1163–70. | |

Donders GGG, Bellen G, Grinceviciene S, et al. Aerobic vaginitis: no longer a stranger. Res Microbiol 2017;168(9–10):845–58. | |

Kaambo E, Africa C, Chambuso R, et al. Vaginal Microbiomes Associated With Aerobic Vaginitis and Bacterial Vaginosis. Front Public Health 2018;6:78. | |

Zarbo G, Coco L, Leanza V, et al. Aerobic Vaginitis during Pregnancy. Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013;2(2):7–11. | |

Donders GG, Van Calsteren K, Bellen G, et al. Predictive value for preterm birth of abnormal vaginal flora, bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis during the first trimester of pregnancy. Bjog 2009;116(10):1315–24. | |

Vidyasagar V. Estimation of incidence of Aerobic vaginitis in women presenting with symptoms of vaginitis. Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Research 2020;8(1):82–5. | |

Fan A, Yue Y, Geng N, et al. Aerobic vaginitis and mixed infections: comparison of clinical and laboratory findings. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287(2):329–35. | |

Zhang T, Xue Y, Yue T, et al. Characteristics of aerobic vaginitis among women in Xi'an district: a hospital-based study. BMC Womens Health 2020;20(1):138. | |

Tempera G, Bonfiglio G, Cammarata E, et al. Microbiological/clinical characteristics and validation of topical therapy with kanamycin in aerobic vaginitis: a pilot study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;24(1):85–8. | |

Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, et al. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(4):850–5. | |

Mendling, W. In: Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis (DIV)/Aerobic Vaginitis (AV): arguments for an immunological disease, XXVI World Congress ISSVD, Dublin, 2022; ISSVD, Ed. Dublin, 2022. | |

Donders GG, Vereecken A, Bosmans E, et al. Definition of a type of abnormal vaginal flora that is distinct from bacterial vaginosis: aerobic vaginitis. BJOG 2002;109(1):34–43. | |

Bradford J, Fischer G. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: differential diagnosis and alternate diagnostic criteria. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010;14(4):306–10. | |

Newbern EC, Foxman B, Leaman D, et al. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: an exploratory case-control study. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12(5):346–52. | |

Costenbader KH, Gay S, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, et al. Genes, epigenetic regulation and environmental factors: which is the most relevant in developing autoimmune diseases? Autoimmun Rev 2012;11(8):604–9. | |

van der Meijden WI, Ewing PC. Papular colpitis: a distinct clinical entity? Symptoms, signs, histopathological diagnosis, and treatment in a series of patients seen at the Rotterdam vulvar clinic. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2011;15(1):60–5. | |

Peacocke M, Djurkinak E, Tsou HC, et al. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis as a manifestation of vitamin D deficiency associated with Crohn disease: case reports and review of the literature. Cutis 2010;86(1):39–46. | |

Pereira N, Edlind TD, Schlievert PM, et al. Vaginal toxic shock reaction triggering desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17(1):88–91. | |

Mendling W. Das Toxic Shock – Syndrom. Gynäkol Prax 1991;16:709–15. | |

Schlievert PM. Effect of non-absorbent intravaginal menstrual/contraceptive products on Staphylococcus aureus and production of the superantigen TSST-1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020;39(1):31–8. | |

Shukla A, Surapaneni S, Sobel JD. Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis as an Extraintestinal Manifestation of Crohn’s Disease. Current Infectious Disease Reports 2020;22(9):24. | |

Yockey L, Dowst S, Zonozi R, et al. Inflammatory vaginitis in women on long-term rituximab treatment for autoimmune disorders. BMC Womens Health 2021;21(1):285. | |

Selva-Nayagam P, Fischer G, Hamann I, et al. Rituximab causing deep ulcerative suppurative vaginitis/pyoderma gangrenosum. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2015;17(5):478. | |

Maloney C, Blickenstaff N, Kugasia A, et al. Vulvovaginal pyoderma gangrenosum in association with rituximab. JAAD Case Rep 2018;4(9):907–9. | |

Vempati YS, Sobel JD. Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis as an Expression of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(4):345–6. | |

Song M, Day T, Kliman L, et al. Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis and Plasma Cell Vulvitis Represent a Spectrum of Hemorrhagic Vestibulovaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(1):60–7. | |

Oerlemans EFM, Wuyts S, Bellen G, et al. The Dwindling Microbiota of Aerobic Vaginitis, an Inflammatory State Enriched in Pathobionts with Limited TLR Stimulation. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(11). | |

Honig E, Mouton JW, van der Meijden WI. Can group B streptococci cause symptomatic vaginitis? Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1999;7(4):206–9. | |

Monif GR. Semiquantitative bacterial observations with group B streptococcal vulvovaginitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1999;7(5):227–9. | |

Yalew GT, Muthupandian S, Hagos K, et al. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis and their associated risk factors among pregnant women from northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2022;17(2):e0262692. | |

Nguyen ATC, Le Nguyen NT, Hoang TTA, et al. Aerobic vaginitis in the third trimester and its impact on pregnancy outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22(1):432. | |

Tao Z, Zhang L, Zhang Q, et al. The Pathogenesis Of Streptococcus anginosus In: Aerobic Vaginitis. Infect Drug Resist 2019;12:3745–54. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Grincevičienė Š, Oliveira C, et al. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Vaginal Wet Mount Microscopy Guidelines: How to Perform, Applications, and Interpretation. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021;25(2):172–80. | |

Ma X, Wu M, Wang C, et al. The pathogenesis of prevalent aerobic bacteria in aerobic vaginitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a narrative review. Reprod Health 2022;19(1):21. | |

Rezeberga D, Lazdane G, Kroica J, et al. Placental histological inflammation and reproductive tract infections in a low risk pregnant population in Latvia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87(3):360–5. | |

Hassan MF, Rund NMA, El-Tohamy O, et al. Does Aerobic Vaginitis Have Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes? Prospective Observational Study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2020;2020:5842150. | |

Kyrgiou M, Moscicki AB. Vaginal microbiome and cervical cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2022;86(Pt 3):189–98. | |

Brusselaers N, Shrestha S, van de Wijgert J, et al. Vaginal dysbiosis and the risk of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221(1):9–18.e8. | |

Ventolini G, Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: IV. The Role of Vaginal Microbiome in Reproduction and in Gynecologic Cancers. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(1):93–8. | |

Plisko O, Zodzika J, Jermakova I, et al. Aerobic Vaginitis-Underestimated Risk Factor for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(1). | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Lima-Silva J, Pinto C, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, aerobic vaginitis, vaginal inflammation and major Pap smear abnormalities. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016;35(4):657–64. | |

Gardella B, Pasquali MF, La Verde M, et al. The Complex Interplay between Vaginal Microbiota, HPV Infection, and Immunological Microenvironment in Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(13). | |

De Seta F, Lonnee-Hoffmann R, Campisciano G, et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: III. The Vaginal Microbiome in Various Urogenital Disorders. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(1):85–92. | |

Marconi C, Donders GG, Bellen G, et al. Sialidase activity in aerobic vaginitis is equal to levels during bacterial vaginosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;167(2):205–9. | |

Murphy R, Edwards L. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis: what is it? J Reprod Med 2008;53(2):124–8. | |

Dong M, Wang C, Li Het al. Aerobic Vaginitis Diagnosis Criteria Combining Gram Stain with Clinical Features: An Establishment and Prospective Validation Study. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12(1). | |

Campisciano G, Zanotta N, Petix V, et al. Vaginal Dysbiosis and Partial Bacterial Vaginosis: The Interpretation of the "Grey Zones" of Clinical Practice. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(2). | |

Donders G, Greenhouse P, Donders F, et al. Genital Tract GAS Infection ISIDOG Guidelines. J Clin Med 2021;10(9). | |

Day T, Wilkinson E, Rowan D, et al. Clinicopathologic Diagnostic Criteria for Vulvar Lichen Planus. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24(3):317–329. | |

Reichman O, Sobel J. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28(7):1042–50. | |

Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial Vaginosis and Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis. N Engl J Med 2018;379(23):2246–54. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Stockdale CK, Sobel J (eds). International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of vaginitis. Lisbon: Admedic, 2023 | |

Murina F, Vicariotto F, Di Francesco S. SilTech: A New Approach to Treat Aerobic Vaginitis. Advances in Infectious Diseases 2016;6(3). | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Stockdale CK, Sobel J (eds). International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of vaginitis. Lisbon: Admedic, 2023 | |

Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, Verstraelen H, et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: V. Therapeutic Modalities of Vaginal Microbiome Engineering and Research Challenges. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(1):99–104. | |

Verstraelen H, Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: I. Research Development, Lexicon, Defining "Normal" and the Dynamics Throughout Women's Lives. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(1):73–8. | |

Döderlein A. Das Scheidensekret und seine Bedeutung für das Puerperalfieber. Leipzig, 1892. | |

Kraut R, Carvallo FD, Golonka R, et al. Scoping review of cytolytic vaginosis literature. PLoS One 2023;18(1):e0280954. | |

Cibley LJ, Cibley LJ. Cytolytic vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165(4 Pt 2):1245–9. | |

Veira-Baptista P, Stckdale CK, Sobel J (eds.) International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of vaginitis. Lisbon: Admedic, 2023. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Silva-Soares S, Lyra J, et al. Wet Mount Microscopy of the Vaginal Milieu Does Not Predict the Outcome of Fertility Treatments: A Cross-sectional Study. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022. | |

Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS, et al. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol 2017;168(9–10):782–92. | |

Linhares IM, Summers PR, Larsen B, et al. Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204(2):120.e1–5. | |

Beghini J, Linhares IM, Giraldo PC, et al. Differential expression of lactic acid isomers, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, and matrix metalloproteinase-8 in vaginal fluid from women with vaginal disorders. Bjog 2015;122(12):1580–5. | |

Yang S, Liu Y, Wang J, et al. Variation of the Vaginal Lactobacillus Microbiome in Cytolytic Vaginosis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24(4):417–20. | |

Xu H, Zhang X, Yao W, et al. Characterization of the vaginal microbiome during cytolytic vaginosis using high-throughput sequencing. J Clin Lab Anal 2019;33(1):e22653. | |

Batashki I, Markova D, Milchev N. [Frequency of cytolytic vaginosis–examination of 1152 patients]. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia) 2009;48(5):15–6. | |

Cerikcioglu N, Beksac MS. Cytolytic vaginosis: misdiagnosed as candidal vaginitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2004;12(1):13–6. | |

Demirezen S. Cytolytic vaginosis: examination of 2947 vaginal smears. Cent Eur J Public Health 2003;11(1):23–4. | |

Hutti MH, Hoffman C. Cytolytic vaginosis: an overlooked cause of cyclic vaginal itching and burning. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2000;12(2):55–7. | |

Soares R, Vieira-Baptista P, Tavares S. Cytolytic vaginosis: an underdiagnosed pathology that mimics vulvovaginal candidiasis. Acta Obstet Ginecol Port 2017;11(2):106–12. | |

Giraldo PC, Amaral R, Gonçalves AK, et al. Influência da freqüência de coitos vaginais e da prática de duchas higiênicas sobre o equilíbrio da microbiota vaginal. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia 2005;27(5). | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Lima-Silva J, Xavier J, et al. Vaginal flora influences the risk of vulvodynia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2017;21:S26. | |

Ventolini G, Gygax SE, Adelson ME, et al. Vulvodynia and fungal association: a preliminary report. Med Hypotheses 2013;81(2):228–30. | |

Awad-Igbaria Y, Palzur E, Nasser M, et al. Changes in the Vaginal Microbiota of Women With Secondary Localized Provoked Vulvodynia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2022;26(4):339–44. | |

Panzarella DA, Peresleni T, Collier JL, et al. Vestibulodynia and the Vaginal Microbiome: A Case-Control Study. J Sex Med 2022;19(9):1451–62. | |

Park SY, Lee ES, Lee SR, et al. Vaginal Microbiome Is Associated With Vulvodynia, Vulvar Pain Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Sex Med 2021;9(2):100314. | |

Silva C, Almeida EC, Côbo Ede C, et al. A retrospective study on cervical intraepithelial lesions of low-grade and undetermined significance: evolution, associated factors and cytohistological correlation. Sao Paulo Med J 2014;132(2):92–6. | |

Yang S, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. Clinical Significance and Characteristic Clinical Differences of Cytolytic Vaginosis in Recurrent Vulvovaginitis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2017;82(2):137–43. | |

Donders G, Slabbaert K, Vancalsteren K, et al. Can vaginal pH be measured from the wet mount slide? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;146(1):100–3. | |

Azevedo S, Lima-Silva J, Vieira-Baptista P. Impact of the Sampling Site in the Result of Wet Mount Microscopy. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2019;23(2):176–81. | |

Santiago GL, Cools P, Verstraelen H, et al. Longitudinal study of the dynamics of vaginal microflora during two consecutive menstrual cycles. PLoS One 2011;6(11):e28180. | |

Garg K, Khare A, Bansal R, et al. Effects of Different Contraceptive Methods on Cervico-Vaginal Cytology. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11(7):Ec09–11. | |

Hillier SL, Austin M, Macio I, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vaginal Discharge Syndromes in Community Practice Settings. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(9):1538–43. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Lima-Silva J, Preti M, et al. Vaginal Leptothrix: An Innocent Bystander? Microorganisms 2022;10(8). | |

Horowitz BJ, Mårdh PA, Nagy E, et al. Vaginal lactobacillosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170(3):857–61. | |

Feo LG, Dellette BR. Leptotrichia (Leptothrix) vaginalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1952;64(2):382–6. | |

Meštrović T, Profozić Z. Clinical and microbiological importance of Leptothrix vaginalis on Pap smear reports. Diagn Cytopathol 2016;44(1):68–9. | |

Pliutto AM. [Laboratory diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis]. Klin Lab Diagn 1997;(3):16–8. | |

Ventolini G, Gandhi K, Manales NJ, et al. Challenging Vaginal Discharge, Lactobacillosis and Cytolytic Vaginitis. J Family Reprod Health 2022;16(2):102–5. | |

Ricci P, Troncoso J. Lactobacillosis and Chronic Vulvar Pain: Looking for High-Risk Factors as Precursors in Women Who Developed Vulvodynia. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2013;20(6). | |

Cepický P, Malina J, Líbalová Z, et al. ["Mixed" and "miscellaneous" vulvovaginitis: diagnostics and therapy of vaginal administration of nystatin and nifuratel]. Ceska Gynekol 2005;70(3):232–7. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)