This chapter should be cited as follows:

Cavaco-Gomes J, Fernandes AS, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.420013

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 12

Infections in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Francesco De Seta, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, University of Trieste, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

Dr Pedro Vieira Baptista, Lower Genital Tract Unit, Centro Hospitalar de São João and Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Chapter

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

First published: January 2024

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending inflammatory process affecting the female upper genital tract.

For information on PID we refer to the 2015 review article published in the New England Journal of Medicine,1 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines2 and to the 2021 Supplement 2 of the Journal of Infectious Diseases entitled “New frontiers in sexually transmitted disease-related pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and other sequelae”.3 Key references of original publications on PID can be found from in these landmark publications.

DEFINITION, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND PATHOGENESIS

Definition

PID designates a medical condition that results from infection and inflammation of the female upper genital tract, involving any or all of the endometrium, fallopian tubes and ovaries, and often extending to pelvic peritoneum and surrounding structure. Traditionally, PID refers to the infection occurring in sexually active women that results from spontaneous ascension of micro-organisms from the lower to the superior genital tract, distinguishing it from pelvic infections related to medical procedures or primary abdominal processes.4,5

Epidemiology

There are limited contemporary data on the prevalence, incidence, or burden of PID worldwide and the true incidence of disease is difficult to accurately estimate given the frequency of mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic disease. Published data suggest an overall decline in the rates and severity of PID in North America and western Europe, likely due to increased screening and treatment of gonorrhea and chlamydia.6,7 Nevertheless, PID remains a frequent and burdensome condition affecting women of reproductive age. Using data from two nationally representative probability surveys collecting self-reported PID history during 2006–2016, it was estimated that more than 2 million reproductive-aged US women have received a PID diagnosis in their lifetime.6

PID causes major medical, social, and economic problems worldwide. Long-term sequelae, specifically tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain are common and extremely costly. It is estimated that PID accounts for 94% of morbidity in women associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV in high-income countries.8

Risk factors

There is a strong correlation between exposure to STIs and PID. Sex and related factors, such as younger age, frequency of intercourse, unprotected intercourse, new or multiple sex partners and prior history of STIs or PID are all associated with exposure to sexually transmitted pathogens and are established risk factors for PID. In one study, it has been estimated that having four or more sexual partners within the prior 6 months increased the risk of PID 3.4 times.9 Likewise, the use of barrier contraception protects against PID. Consistent use of condoms may reduce the risk of gonococcal and chlamydial cervical infections for about 50% and the risk of recurrence of PID for 30–60%.10 Tubal ligation may prevent the spread of the infection to the distal portion of the tubes, eventually reducing the risk of extrauterine involvement.

There might be a little risk of PID related to intrauterine device (IUD) use, which seems to be limited to the first 3 weeks after the insertion. When PID develops in women with an IUD already in place, most guidelines currently recommend not to remove it while treating PID, unless there is no clinical improvement in a few days.5

Pathogenesis

The endocervical canal is considered a protective barrier of the upper genital tract. Endocervical infection with sexually transmitted pathogens breaches this barrier and gives vaginal bacteria access to the upper genital organs, infecting the endometrium, then the endosalpinx, ovaries, pelvic peritoneum, and underlying organs. Susceptibility to infection may be related to genetic, immunological, and hormonal factors.11 Sexual intercourse and retrograde menstruation may promote the movement of organisms from the lower to the upper genital tract.1

Infection-induced inflammatory response leads to scarring and adhesions involving the upper genital tract organs. This will eventually result in partial or total obstruction of the fallopian tubes and impaired ovum transport function of their ciliated epithelium, thus increasing the risk for tubal-factor infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Adhesions involving pelvic organs may also lead to chronic pelvic pain.1

Microbiology

The sexually transmitted pathogens Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are the two most commonly identified pathogens in PID. It has been estimated that about 15% of untreated chlamydial infections progress to clinical PID, and the risk after gonococcal infection may be even higher.1 However, more than half of women with clinical signs and symptoms and histologically confirmed PID do not have either sexually transmitted pathogen detected.8 Other cervical microbes (such as Mycoplasma genitalium), as well as facultative and anaerobic bacteria responsible for bacterial vaginosis (e.g., Peptostreptococcus species, Bacteroides species), respiratory pathogens (e.g., Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus), enteric pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, group B Streptococcus), and pathogens associated with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) (e.g., group B Streptococcus, enterococcus, E. coli) have also been implicated in PID.1,8

The relative importance of different pathogens varies between different regions. Regardless of the initiating pathogen, for clinical purposes PID should be considered as a mixed (facultative and anaerobic) polymicrobial infection.2,12

CLINICAL PRESENTATION, EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

History

PID is more common among young and adolescent women. Most cases are seen in outpatient clinics, emergency rooms, and physician offices. The symptoms associated with acute PID include pelvic and lower abdominal pain of varying severity, abnormal vaginal discharge, dysuria, and often abnormal bleeding. Fever or other systemic manifestations are often not present. Right upper quadrant pain suggests simultaneous presence of perihepatitis, also known as Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome.1,2

Asymptomatic or subclinical PID also exists. Many women with tubal factor infertility (TFI) have no history of diagnosed PID, but report a history of health care visits for abdominal pain. This suggests that many cases of PID are missed. Therefore, clinicians should have a low threshold for the clinical diagnosis of PID.

Clinical research on PID became a hot topic in the 1960s when Swedish physician-scientists introduced laparoscopy as the gold standard for the diagnosis of PID. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a substantial amount of research on the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of PID in the United States and Europe. However, PID research has subsequently leveled off and has in fact been strikingly limited during the past two decades.

Pelvic examination

Diagnostic criteria for the provisional clinical diagnosis of PID have been recommended by the CDC, and by many other organizations.1,2 The clinical diagnosis of PID is based on the finding of pelvic organ tenderness, i.e., cervical motion tenderness, adnexal tenderness, or uterine tenderness on bimanual pelvic examination, together with signs of lower genital tract infection and inflammation. Signs of lower genital tract inflammation include the presence of cervical mucopus, easily induced cervical mucosal bleeding, and increased number of white cells observed on microscopic wet mount examination of vaginal discharge. Pelvic tenderness has high sensitivity, but low specificity for the diagnosis of PID. Findings of lower genital tract infection and inflammation increase the specificity of the diagnosis. However, only approximately three out of four women with a clinical diagnosis of PID turn out to have PID by laparoscopic visualization of the pelvis.

Additional diagnostic tools

Laparoscopy is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of PID, although the interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility of the laparoscopic diagnosis have been poorly studied. The laparoscopic diagnosis of severe PID is usually straightforward, but the same is not true for mild/early PID or endometritis. Laparoscopy is an invasive surgical procedure that is not complication free. Laparoscopy is not readily available in clinical settings where most women with low abdominal pain are seen.

Transcervical endometrial aspiration biopsy with histopathological findings of plasma cell endometritis confirms the diagnosis of PID, but results in delayed diagnosis. The absence of leukocytes in wet mount microscopy has a very high negative predictive value.1

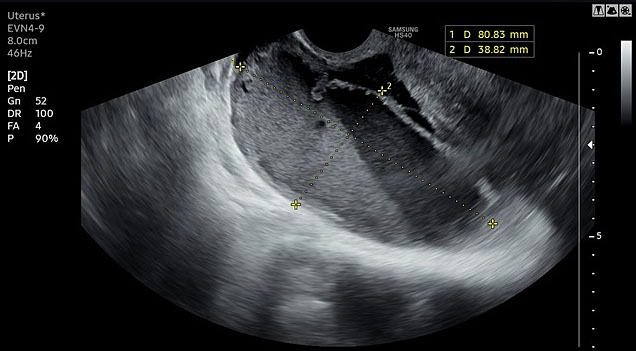

Imaging studies augment the diagnosis of PID and are useful in differential diagnostic problems among women with low abdominal pain, such as ovarian cyst, endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, or acute appendicitis. Transvaginal ultrasound is a procedure routinely performed in outpatient clinics. Several specific ultrasound findings have been identified as suggestive of PID in experienced hands (Figure 1), although the exact test accuracy has not been extensively studied.1

1

Transvaginal ultrasound revealing pyosalpinx in a patient with acute PID.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has even higher sensitivity than transvaginal ultrasound, but may not be readily available in emergency room settings.

Patients with suspected PID should have cervical, vaginal, or first-void urine nucleic acid amplification tests for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. The etiologic role of M. genitalium in PID is still controversial, although it is an accepted cause of nongonococcal urethritis in men. Further research of interactions between M. genitalium and vaginal microbiota is needed in order to more definitively determine the independent role of M. genitalium in PID.13

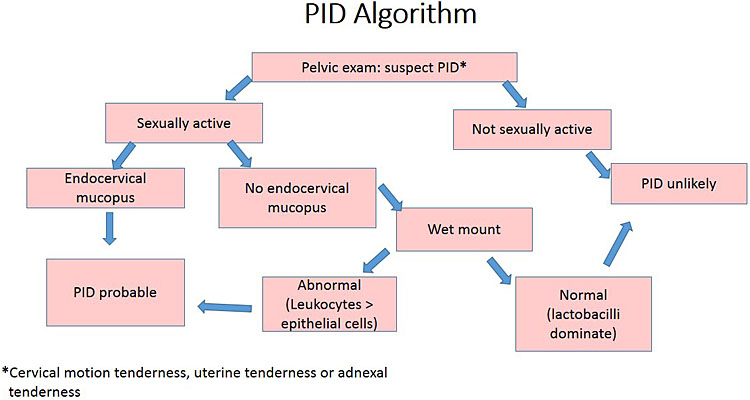

Vaginal wet mount microscopy is an important bed-side test in the diagnostic work-up of women with suspected PID, and an essential part of the diagnostic algorithm (Figure 2). The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis or desquamative inflammatory vaginitis increases the likelihood of PID, whereas the presence of lactobacilli and absence of leukocytes is consistent with healthy vagina and largely rules out PID.

2

Simplified algorithm for the clinical diagnosis of PID. Reprinted with permission from Brunham et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372(21):2039-481 © (2015) Massachusetts Medical Society.

Additional laboratory tests such as C-reactive protein (CRP) are also useful as diagnostic indicators of upper genital tract inflammation. Elevated CRP increases the specificity of the clinical diagnosis of PID among women with low abdominal pain.

Conclusions

Clinical diagnosis of PID remains a challenge. The clinical diagnosis of PID lacks sensitivity and specificity. There has been strikingly little progress during the past 20 years in the development of new tests to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of PID. Imaging studies or laparoscopy are needed to solve differential diagnostic problems.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Treatment: general considerations

To prevent short- and long-term complications, treatment is indicated for patients with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease, even in the presence of subtle or minimal symptoms.

Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone treatment and it requires broad antimicrobial coverage, including C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and a variety of aerobic and anaerobic organisms commonly isolated from the upper genital tract.

Although the optimal treatment regimen remains undefined, the selection should consider the severity of the infection (hospitalization versus outpatient management), cost, convenience of administration, safety, formulary availability, and allergy history.

Outpatient treatment

In the absence of criteria for hospitalization (see section below: Hospitalized patients), outpatient therapy is as effective as inpatient treatment for patients with clinically mild to moderate PID.14 Table 1 describes the antibiotic regimens.2

1

Preferred and alternative regimens for PID outpatient treatment.

PREFERRED REGIMEN | ||||||

Ceftriaxone | PLUS | Doxycycline | PLUS | Metronidazole | ||

500 mg if <150 kg 1 g if >150 kg | 100 mg | 500 mg | ||||

Intramuscular | Orally | Orally | ||||

Single dose | 14 days | 14 days | ||||

ALTERNATIVE REGIMEN | ||||||

Cefoxitin | PLUS | Probenecid | PLUS | Doxycycline | plus | Metronidazole |

2 g | 1 g | 100 mg | 500 mg | |||

Intramuscular | Orally | Orally | Orally | |||

Single dose | Single dose | 14 days | 14 days | |||

OR | ||||||

Other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftizoxime or cefotaxime) | PLUS | Doxycycline | PLUS | Metronidazole | ||

100 mg | 500 mg | |||||

Orally | Orally | |||||

14 days | 14 days | |||||

Although the optimal choice of a cephalosporin is uncertain, ceftriaxone is recommended because it is the cephalosporin that provides coverage against gonorrhea. The addition of metronidazole to these regimens provides extended coverage against anaerobic organisms and thus also treats BV, which is frequently associated with PID.12,15

Patients selected for outpatient treatment must be evaluated within 48 to 72 hours. If there is no clinical improvement, complications must be excluded and alternative diagnosis must be considered. These patients warrant hospitalization for parenteral intravenously therapy.

The risk for penicillin cross-reactivity is highest with first-generation cephalosporins but is negligible between the majority of second-generation (e.g., cefoxitin) and all third-generation (e.g., ceftriaxone) cephalosporins.16,17

For patients with cephalosporin allergy, who are likely to comply with follow-up, and if the prevalence in the community and individual risk of gonorrhea are low, alternative therapy for 14 days can be considered with one of the following alternative regimens:

2

Alternative antibiotic regimens for PID treatment in patients with cephalosporin allergy.

ALTERNATIVE REGIMENS | ||

Levofloxacin | PLUS | Metronidazole |

500 mg | 500 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Once daily for 14 days | Twice daily for 14 days | |

OR | ||

Moxifloxacin | ||

400 mg | ||

Orally | ||

Every 6 hours for 14 days | ||

OR | ||

Azithromycin | ||

500 mg | ||

Intravenously | ||

Daily for 1 or 2 days | ||

followed by 250 mg orally daily for a total azithromycin duration of 7 days | PLUS | Metronidazole |

Diagnostic tests for gonorrhea should be obtained before starting therapy, and if positive treatment should be tailored according to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. If N. gonorrhoeae is quinolone-resistant or if antimicrobial susceptibility cannot be assessed, counseling with an infectious disease specialist is recommended

Hospitalized patients

Indications for hospitalization are as follows:

1. Severe clinical illness, fever ≥38.5°C [101°F], nausea and vomiting.

2. Complicated PID with pelvic abscess (including tubo-ovarian abscess).

3. Possible need for invasive diagnostic evaluation for alternate etiology (e.g., appendicitis or ovarian torsion) or surgical intervention for suspected ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess.

4. Inability to take oral medications.

5. Pregnancy.

6. Lack of response or tolerance to oral medications.

7. Concern for nonadherence to therapy.

The selection of antibiotics, should be as follows:2

3

First-line antibiotic regimens for PID treatment in hospitalized patients during 24–48 hours after clinical improvement.

FIRST-LINE REGIMENS | ||||

Ceftriaxone | PLUS | Doxycycline | PLUS | Metronidazole |

1 g | 100 mg | 500 mg | ||

Intravenously | Orally or intravenously | Orally or intravenously | ||

Every 24 hours | Every 12 hours | Every 12 hours | ||

OR | ||||

Cefoxitin | PLUS | Doxycycline | ||

2 g | 100 mg | |||

Intravenously | Orally or intravenously | |||

Every 6 hours | Every 12 hours | |||

OR | ||||

Cefotetan | PLUS | Doxycycline | ||

2 g | 100 mg | |||

Intravenously | Orally or intravenously | |||

Every 12 hours | Every 12 hours | |||

Considering that the bioavailability of the oral and parenteral formulations is equivalent for both doxycycline and metronidazole and the pain associated with intravenous doxycycline administration, oral administration is generally preferred for these drugs, if the patient can tolerate it. Cefoxitin and cefotetan have intrinsic anaerobic activity; metronidazole is added if other parenteral second- or third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftizoxime or cefotaxime) are chosen, to provide anaerobic coverage.

4

Alternative antibiotic regimens for PID treatment in hospitalized patients during 24–48 hours after clinical improvement.

ALTERNATIVE REGIMENS (if allergy or unavailability of the preferred regimens) | ||

Clindamycin | PLUS | Gentamicin |

900 mg | 3 to 5 mg/Kg | |

Intravenously | Intravenously or intramuscular | |

Every 8 hours | Daily | |

OR | ||

2 mg/kg intravenously or intramuscular once, followed by 1.,5 mg/Kg every 8 hours | ||

OR | ||

Ampicillin-sulbactam | PLUS | Doxycycline |

3 g | 100 mg | |

Intravenously | Orally or intravenously | |

Every 6 hours | Twice daily | |

Transition to oral therapy

Twenty four to 48 h after clinical improvement (resolution of fever, nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain, if initially present), the patient can transition to oral therapy and complete a 14-day course of doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) plus metronidazole (500 mg twice daily).2 For those who cannot tolerate doxycycline the alternative is azithromycin (500 mg for 1 to 2 days followed by 250 mg once daily to complete a 14-day course) and for metronidazole intolerance the alternative is clindamycin (450 mg orally every 6 hours).

Tubo-ovarian abscess

Treatment of tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) requires hospitalization either for parenteral antibiotics and/or image-guided drainage procedures or surgery. The selection depends on the hemodynamic stability of the patient, menopausal status and size of the abscess.

Parenteral antibiotics

In a stable pre-menopausal female, with a TOA less than 70 mm without clinical signs of rupture, parenteral antibiotics are the first-line treatment, with an efficiency rate of approximately 70%.18,19

For postmenopausal women with low suspicion of malignancy and proper counseling, nonsurgical management is a reasonable option, and serial imaging studies are required to demonstrate complete resolution of the pelvic mass. If the mass does not resolve, surgery is required.

According to the CDC, the selected first-line and alternative regimens for TOA are those recommended for PID in general (see section 3 – Hospitalized patient. Inpatient observation should last at least for 24 hours2 but most of the clinicians prefer treatment and observation for 48 to 72 hours.

When there is clear clinical improvement (afebrile for at least 24 to 48 hours, white blood cell counts normalized, no abdominal pain), the patient can tolerate oral medication and will comply with follow-up, she can be discharged. Although there are no data available to formally guide length of therapy, usually patients must complete a 14-day course with one of the following:

5

Antibiotic regimens to complete a 14-day course treatment for tubo-ovarian abscess.

ANTIBIOTIC REGIMENS | ||

Metronidazole | PLUS | Doxycycline |

500 mg | 100 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Twice daily | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Clindamycin | PLUS | Doxycycline |

450 mg | 100 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Every 6 hours | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Levofloxacin | PLUS | Metronidazole |

500 mg | 500 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Once daily | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Moxifloxacin | PLUS | Metronidazole |

400 mg | 500 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Once daily | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Azithromycin | PLUS | Metronidazole |

500 mg day 1 followed by 250 mg on subsequent days | 500 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Daily | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Ofloxacin | PLUS | Metronidazole |

400 mg | 500 mg | |

Orally | Orally | |

Twice daily | Twice daily | |

OR | ||

Amoxicillin-clavulanate XR (extended release) | ||

2 g | ||

Orally | ||

Twice daily | ||

If there is no improvement of the clinical state or inflammatory parameters, 48/72 h after parenteral antibiotics, either image-guided abscess drainage or surgery is required. Notice that despite the choice of additional interventions, antibiotic therapy should be used in combination and maintained for at least 14 days.

Image-guided drainage procedures

According to some case series, invasive image-guided drainage procedures have a 70 to a 100% success rate, particularly in unilocular lesions.20,21,22

Besides women with failed parenteral antibiotic treatment at the initial approach, image-guided drainage can also be considered in hemodynamically stable pre-menopausal female with high surgical risk and TOA greater than 70 mm.

The approach depends on the experience of the physician, technology available, and the anatomical location of the abscess.

Surgical treatment

Surgical exploration is the first-line treatment in the following situations:

1. Unstable patients with signs of sepsis and/or abscess rupture.

2. Hemodynamically stable post-menopausal women, because of the potential underlying of malignancy (always consider intraoperative frozen section analysis of the adnexal mass).23

3. Pre-menopausal female, stable, with an abscess greater than 70 mm.24

4. No clinical or analytical improvement after 24 to 48 h of parenteral antibiotics in premenopausal female, with TOA less than 70 mm.

The choice of surgical approach depends on operator skill, experience, and ability to perform the necessary surgical maneuvers given the anatomic distortion.

Classically, laparotomy is the surgical route used by most gynecologic surgeons for treatment of TOA. However, nowadays there is some evidence of the safety and improved outcomes in laparoscopic approach, when in expert hands.25

A conservative approach is adequate and has major advantages, considering that most of the women affected are in reproductive age. In women who have completed childbearing, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy may be may be appropriate.

Special considerations

All patients diagnosed with acute PID must be screened for B hepatitis, HIV, syphilis, and vaccinated for B hepatitis if adequate.2

They must be counseled to avoid sexual intercourse until they have completed therapy, their symptoms have resolved, and sex partners have been evaluated and/or treated for potential sexually transmitted infections. Although the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends tracing of contacts within a 6-month period before onset of symptoms, the CDC is more restrictive, considering that only the male sex partners for up to 60 days before the diagnosis must be examined and presumptively treated for chlamydial or gonococcal infection.

If PID is associated with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection, follow up for retesting at 3 months is necessary or, if not possible, at any medical care visit less than 12 months after the treatment.

Special populations

Female with intrauterine devices (IUD)

It is not necessary to remove the IUD in a patient with PID, unless there is no clinical improvement with antibiotic therapy for at least 72 hours or in severe disease cases.2,12

Immunocompromised patient

Should be treated in the same manner as other patients.

LONG-TERM SEQUELAE

Despite prompt diagnosis and treatment, sequelae of PID occur, namely chronic pelvic pain, tubal factor infertility, and ectopic pregnancy. The scarring and adhesion formation are mostly responsible for the complications, and hydrosalpinx can be found in any of these situations. A crucial risk factor for long-term sequelae is recurrent episodes of PID.

Chronic pelvic pain

It occurs in approximately one-third of females with previous PID and has a strong association with recurrent PID.

Infertility

PID usually affects the fallopian tubes, with loss of ciliary action, fibrosis, and occlusion, leading to tubal infertility. Also, endometritis even if subclinical has a negative impact in subsequent fertility. The major risk factors are as follows:

1. Delay in seeking care for PID.

2. Severity of infection.

3. Increasing number of PID episodes.

4. Chlamydial infection.

Ectopic pregnancy

Once again, tubal damage prompts ectopic pregnancy.

Considering this, the main goal after adequate diagnosis and treatment of the first episode of PID, is to prevent recurrence.26 Women should be counseled for the importance of consistent condom use by their sexual partner and consider hormonal contraception, specially progestins.

With the aim of decreasing the burden of PID, the CDC recommends annual screening for C. trachomatis in sexually active women with less than 25 years and also for women older than 25 years with C. trachomatis infection risk, including their respective sexual partners.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH NEEDS

Research needs for the improvement of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease have been identified at a 2011 National Institutes of Health Workshop but after more than 10 years, most of the topics remain to be addressed (Table 6).

Permission to use Table 6 is still awaited

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- The most important public health measure for the prevention of PID is the prevention of C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection.

- Prompt evaluation and empirical treatment of male sexual partners of women with PID are essential; expedited treatment of the partner is a useful approach to reduce the risk of reinfection.

- Clinicians should have a low threshold for considering the diagnosis of PID among women with history of low abdominal pain.

- A simplified algorithm (Figure 1) is recommended for guiding the clinical diagnosis of PID.

- To prevent short- and long-term complications, treatment is indicated for patients with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease, even in the presence of subtle or minimal symptoms.

- Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone treatment and it requires broad antimicrobial coverage, including C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and a variety of aerobic and anaerobic organisms.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. In: Campion EW. (ed.) N Engl J Med [Internet] 2015;372(21):2039–48. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMra1411426. | |

Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Reports [Internet] 2021;70(4):1–187. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/rr/RR7004a1.htm?s_cid=RR7004a1_w. | |

New Frontiers in Sexually Transmitted Disease-related Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, Infertility, and Other Sequelae. J Infect Dis 2021;224(Suppl 2, 15):S23–2160. | |

Paavonen J. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Dermatol Clin [Internet] 1998;16(4):747–56. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0733863505700413. | |

Ford GW, Decker CF. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Disease-a-Month [Internet] 2016;62(8):301–5. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0011502916000894. | |

Kreisel KM, Llata E, Haderxhanaj L, et al. The Burden of and Trends in Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in the United States, 2006–2016. J Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;224(Suppl 2):S103–12. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/Supplement_2/S103/6352163. | |

Davis GS, Horner PJ, Price MJ, et al. What Do Diagnoses of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Specialist Sexual Health Services in England Tell Us About Chlamydia Control? J Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;224(Suppl 2):S113–20. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/Supplement_2/S113/6352149. | |

Hillier SL, Bernstein KT, Aral S. A Review of the Challenges and Complexities in the Diagnosis, Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. J Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;224(Suppl 2):S23–8. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/Supplement_2/S23/6352150. | |

Brody H, Hermer LD, Scott LD, et al. Artificial nutrition and hydration: The evolution of ethics, evidence, and policy. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(9):1053–8. | |

Ness RB, Randall H, Richter HE, et al. Condom Use and the Risk of Recurrent Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, Chronic Pelvic Pain, or Infertility Following an Episode of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2004;94(8):1327–9. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1327. | |

Zheng X, Zhong W, O’Connell CM, et al. Host Genetic Risk Factors for Chlamydia trachomatis - Related Infertility in Women. J Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;224(Suppl 2):S64–71. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/Supplement_2/S64/6352152. | |

Ross J, Guaschino S, Cusini M, et al. 2017 European guideline for the management of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J STD AIDS [Internet] 2018;29(2):108–14. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956462417744099. | |

Mitchell CM, et al. Etiology and diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease: Looking beyond gonorrhea and chlamydia. J Infect Dis 2021:224(Suppl 2);S29–35 | |

Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: Results from the pelvic inflammatory disease evaluation and clinical health (peach) randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2002;186(5):929–37. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S000293780289353X. | |

Wiesenfeld HC, Meyn LA, Darville T, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Ceftriaxone and Doxycycline, With or Without Metronidazole, for the Treatment of Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;72(7):1181–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/72/7/1181/5735325. | |

Park MA, Koch CA, Klemawesch P, et al. Increased Adverse Drug Reactions to Cephalosporins in Penicillin Allergy Patients with Positive Penicillin Skin Test. Int Arch Allergy Immunol [Internet] 2010;153(3):268–73. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/314367. | |

Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, et al. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet [Internet] 2019;393(10167):183–98. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618322189. | |

Lareau SM, Beigi RH. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-ovarian Abscess. Infect Dis Clin North Am [Internet] 2008;22(4):693–708. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0891552008000469. | |

Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Soft tissue infection and pelvic abscess. In: Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract, 5th edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2009. | |

Nelson AL, Sinow RM, Oliak D. Transrectal ultrasonographically guided drainage of gynecologic pelvic abscesses. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2000;182(6):1382–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002937800358513. | |

Gjelland K, Ekerhovd E, Granberg S. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration for treatment of tubo-ovarian abscess: A study of 302 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2005;193(4):1323–30. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002937805008665. | |

Hiller N, Sella T, Lev-Sagi A, et al. Computed tomographic features of tuboovarian abscess. J Reprod Med [Internet] 2005;50(3):203–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15841934. | |

Protopapas AG, Diakomanolis ES, Milingos SD, et al. Tubo-ovarian abscesses in postmenopausal women: gynecological malignancy until proven otherwise? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol [Internet] 2004;114(2):203–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301211503005554. | |

Fouks Y, Cohen A, Shapira U, et al. Surgical Intervention in Patients with Tubo-Ovarian Abscess: Clinical Predictors and a Simple Risk Score. J Minim Invasive Gynecol [Internet] 2019;26(3):535–43. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1553465018303352. | |

Shigemi D, Matsui H, Fushimi K, et al. Laparoscopic Compared With Open Surgery for Severe Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-Ovarian Abscess. Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2019;133(6):1224–30. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00006250-201906000-00021. | |

Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, et al. Recurrent PID, Subsequent STI, and Reproductive Health Outcomes: Findings From the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Sex Transm Dis [Internet] 2011;38(9):879–81. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00007435-201109000-00018. | |

Vieira-Baptista P, Grincevičienė Š, Oliveira C, et al. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Vaginal Wet Mount Microscopy Guidelines: How to Perform, Applications, and Interpretation. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021;25(2):172–80. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000595. PMID: 33631782. | |

Yudin MH, Hillier SL, Wiesenfeld HC, et al. Vaginal polymorphonuclear leukocytes and bacterial vaginosis as markers for histologic endometritis among women without symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(2):318–23. | |

Darville T. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Sex Transm Dis [Internet] 2013;40(10):761–7. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00007435-201310000-00001. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)