This chapter should be cited as follows:

Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416213

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 12

Operative obstetrics

Volume Editor: Professor Owen Montgomery, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA

Chapter

Management of Morbid Adherent Placenta/Placenta Accreta Spectrum (MAP/PAS) in a Low-Resource Setup without Hysterectomy

First published: June 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The first series of cases that described placenta accreta (PA) was published in 1937 by Irving and Hertig. They described it clinically as “the abnormal adherence of the afterbirth in whole or in parts to the underlying uterine wall” and histologically as “the complete or partial absence of the decidua basalis”. This description is still used by pathologists. They described all of their cases as “vera” or “adherenta” where the villi were attached to the surface of the myometrium without invading it.

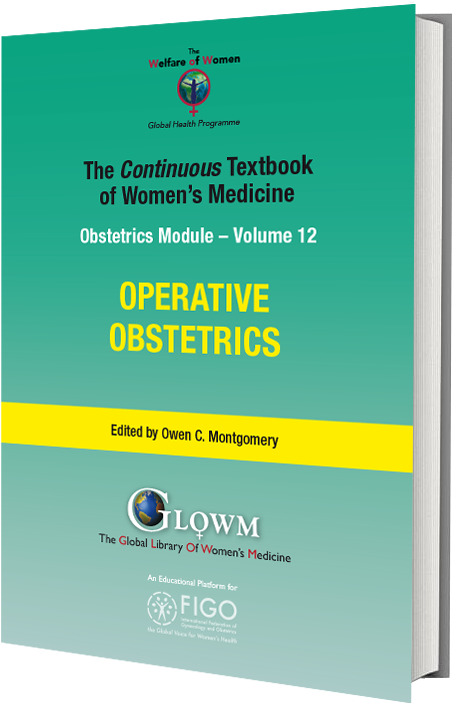

The grading classification of PA according to the depth of villous invasiveness inside the myometrium was introduced by modern pathologists in the 1960s. Different degrees of placental invasion can co-exist in the same uterine specimen, thus making a precise histopathological classification difficult. Despite their huge impact on maternal and fetal well-being, there are still several controversies on classification, diagnosis, and management of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders (Figure 1).

1

Classification of morbid adherent placenta (MAP)/placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), usually after cesarean section (CS). (1) Placenta previa (PP). (2) Placenta accreta (PA). (3) Placenta increta (PI). (4) Placenta percreta (PPer).

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has recently proposed a clinical classification of PAS disorders based upon the difficulties in placental detachment for the basal plate at delivery and the gross visualization of invasion during surgery.1 The differences in the definition of PAS are likely to account for the large heterogeneity in the incidence of such disorders reported in the previously published literature.

Moreover, there is strong evidence that the incidence of PAS disorders increases with the number of previous cesarean deliveries.2

Similarly, the ratio of adherent/invasive accreta placentas has changed from 70/30 in the 1970s to 50/50 in the last two decades. A change that can be linked to the increase in parity with multiple cesarean scars allowing for deeper and extended villous invasion in subsequent pregnancies.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Morbid adherent placenta (MAP)/placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is one of the most morbid conditions obstetricians will encounter. The rate has dramatically increased in the last 20 years. The three forms of MAP: placenta accreta, increta, and percreta, present a significant obstetric challenge, at times resulting in life-threatening bleeding and/or peripartum hysterectomy.3

Myometrial tissue trauma and scarring are the main predisposing factors resulting in both placenta previa and morbidly adherent placenta. This can be caused by multiple cesarean sections; this risk rises as the number of prior cesarean sections increases. Placenta accreta spectrum is not exclusively a consequence of cesarean delivery. Other surgical trauma to the integrity of the uterine endometrium and/or superficial myometrium, such as dilatation and curettage and other surgical injuries to the myometrium: manual removal of the placenta, postpartum endometritis, or myomectomy, has been associated with accreta placentation in subsequent pregnancies, as well as, assisted reproductive technology and maternal smoking.4

MAP/PAS poses dramatic risk for massive obstetric hemorrhage along with serious complications such as consumption coagulopathy, multisystem organ failure, and maternal mortality. The surgical management choices may be considered according to available expertise, as well as geographical and individual circumstances.5 In addition, there is an increased risk for surgical complications such as injury to bladder, ureters, and bowel and the need for reoperation. Most women require massive blood transfusion; many require admission to an intensive care unit. As a result of urgent intervention, preterm delivery is one of the sequalae expected in many cases, and often ends up by admission to a neonatal care intensive care unit. Centers of excellence in MAP/PAS management improve outcomes where multidisciplinary expertise and experience take care of MAP/PAS patients. Such expertise may include maternal−fetal medicine, gynaecologic surgery, gynaecologic oncology, vascular, trauma and urologic surgery, transfusion medicine, intensivists, neonatologists, interventional radiologists, anaesthesiologists, specialized nursing staff, and ancillary personnel.

We recommend and believe in multidisciplinary team-work, however this is not always feasible in a low-resource setup.

The best and first step in dealing with MAP/PAS mandates setting clear strategies in patient early diagnosis, referral, patient selection, follow up, care and management tailored specifically from diagnosis to best possible outcome.

Ultrasound scan and Doppler are first-line investigations with high sensitivity. Transabdominal ultrasound is non-invasive; however, it may be difficult to visualize the lower uterine segment. Transvaginal ultrasound and color Doppler may improve the diagnostic accuracy especially in patients with placenta previa as it allows detailed visualization. Recent studies looking at the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have not demonstrated superiority of this modality over transvaginal ultrasound.6

An accurate prenatal diagnosis is required to reduce the risk of maternal/fetal morbidity and mortality. Ultrasonography is used routinely for diagnosis of MAP/PAS, although diagnostic criteria and accuracy are still subject to debate. Two-dimensional (2D) power Doppler ultrasound could represent a turning point for diagnosis of abnormal placentation. MRI can be helpful when the placenta is difficult to visualize on ultrasound due to the patient’s body habitus or to a posterior location of the placenta and is rarely required.

A finding of placenta previa should elicit a detailed evaluation for MAP/PAS especially with a history of previous cesarean section, including color Doppler imaging and a transvaginal ultrasound scan.

Placental lacunae: Placental lacunae have been the most predictive ultrasound scan finding for MAP/PAS, and often appear to be parallel linear vascular channels extending from the placental parenchyma into the uterine wall musculature. Presence of lacunae has the highest sensitivity in the diagnosis of MAP/PAS from the early second-trimester period and increasing numbers of lacunae are associated with increased risk for MAP/PAS.

In MAP/PAS numerous large blood vessels are often seen surrounding the myometrium, possibly caused by the invasion of surrounding structures. However, increased vascularity is seen in any MAP/PAS. Invasion can also create an irregular bladder wall with extensive associated vascularity.

Loss of retroplacental clear space: A retroplacental hypoechoic line is usually seen with normal placentation; it is one of the more obvious findings at screening evaluation and should prompt a detailed evaluation for other ultrasound scan markers.

Reduced uterine wall thickness: One of the predictors for MAP/PAS is reduction of the myometrium thickness to less than 3 mm (as measured between the echogenic serosa and the retroplacental vessels).

Careful assessment of the case with a full bladder in the early third trimester will show the stair step appearance (Fazari’s sign), which is seen quite commonly among many cases of MAP/PAS, and a reviewed ultrasound scan and clinical observation with reported intraoperative findings, where triad (Dubai’s triad) is strongly associated with stair step appearance, in ultrasound scan appears as follows:

- Ballooning of the lower segment all around as it is occupied by the whole placenta.

- Complete loss of uterine wall replaced by vascular bed.

- Badly adherent urinary bladder with penetrated space by the placenta and its vasculature.

In practice and during surgery as all cases are managed surgically, those cases are as follows:

- Technically exceedingly difficult.

- High risk for urinary bladder injury without this sign.

- Long-time of surgery.

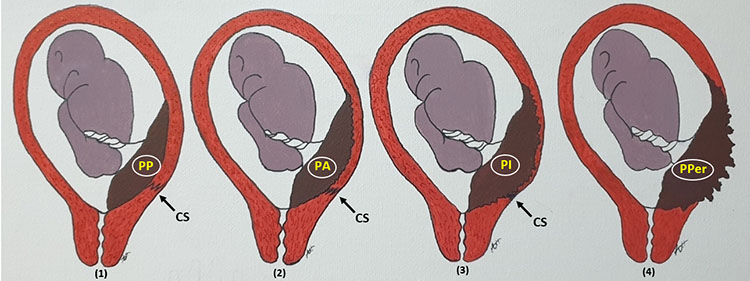

Anticipating the challenges and the outcome of each case of MAP/PAS by using the above-mentioned sign and triad, can prevent major complications that may occur and yield a good prognosis for the patient (Figure 2).

2

MAP/PAS (P) with loss of hypoechoic line of the myometrium (P − yellow arrows) and clear urinary bladder invasion (B − red arrows) Covering the cervix (C) and the fetal head seen cranially (H). (This mobile shot was from the USS machine screen.)

The standard health system scales from primary healthcare, secondary healthcare level, and then the tertiary healthcare level, reaching the very highly specialized health centers. Providing proper essential health services and the added service needs for the community through all levels and the highly specialized standard care is pivotal.

The health system in most of the developing countries, if not all, is below the standard of other international health systems and this is most related to poor infrastructures and the poverty in these parts of the world.

Rural and discrete hospitals are usually run by a single doctor who has often received obstetric training to manage critical obstetrical emergencies by either safely transferring the patient early on by timely diagnosis or doing whatever they can to save the patient's life and then transferring them for further management. Those doctors have also attended some professional training courses in ultrasound. Around these doctors, some trained nurses, certified midwives, rural midwives, and health supervisors cover the maternity services in the surrounding villages, nomadic, and pastoral tribes. These hospitals have extremely limited resources in electricity, water supply, drugs, medical consumables, logistics, buildings construction, and maintenance. The sources of medical supply are usually shared by some governmental input, charity donation from pharmaceutical companies by personal efforts, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Lack of development components and perfect infrastructures challenge the health system and adversely affect the patient outcome.

The transportation of the patient from their site or village to the nearest town with a hospital is missed most of the time and lags behind the standard time in which the patient should arrive safely for the next services. Hemorrhage, eclampsia, and sepsis are still the main causes of maternal morbidity and mortality in this remote part of the world with a low-resource setup; usually hemorrhage sits on top of the list.

During rainy seasons, some areas become water blocked areas where there is no transportation movement because all areas are surrounded and covered by floods. This major challenge leads to late arrival/no arrival and contributes to serious maternal mortality and death.

Placenta accreta spectrum is a dangerous cause of obstetric hemorrhage; antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum lead maternal morbidity and mortality.

The electrical currency is either based or supported by a separate electrical generator for the light and sterilization and electro-thermal devices. This makes dramatic and luxurious improvement in the surgical setup. This electrical generator is switched on temporarily during the surgery period to provide electrical supply for the operation theater only and USS machine. The theater light is run by at least two chargeable mobile sealing lamps.

Selection criteria for this conservative uterine surgery in MAP/PAS:

- Patients with low parity or who have not completed their family.

- Patients with bad obstetrical history and no living baby.

- Patients with a history of myomectomy where this is their first or second pregnancy when diagnosed as a case of MAP/PAS.

Generally, for patients who have completed their family the preference is to proceed with cesarean hysterectomy; or if the condition is not promising for bleeding control the hysterectomy should be a timed decision.

Elective admission of a MAP/PAS case after diagnosis is considered most of the time, with respect to some circumstances like gestational age, accompanied person, and distance from and to the hospital. This admission affects the family and as well burdens the health system and hospitals.

On the other hand, the great benefit of admission is the patient is prepared medically and psychologically, and management options are well planned and studied. It is very safe for the patient to be in hospital during rainy season due to the considerable confinement and being kept away from the stress of staying in hospital in case of an emergency and not losing contact.

During the patient's stay and before surgery they receive good counseling and support from a trained social worker (or acting social worker) and from the treating doctors about the surgery’s detail and expected outcome with the possible risks and the precautions taken to overcome these issues.

All comorbidities will be well evaluated by medical and anesthesia staff.

General anesthesia is the best preferred method in such surgery and surgery is usually performed early in the morning after proper documentation and consent.

Blood transfusions remain the cornerstone in MAP/PAS management with the following strong challenges:

- Availability on time.

- Poor or no blood-bank facility.

- Seldomly blood products may be at hand.

Implementation of mobile blood donor plans, especially in areas where there is no electricity supply for the blood refrigerator, requires family members or friends to be tested, screened, and cross matched with the patient's blood group and shortly before surgery, during surgery, or when blood is needed, it will be extracted from the donor and given directly to the patient. These services will be provided by a well-trained nurse or sometimes a blood-bank technician, if available.

Patient blood management is an important treatment tool for anemia, which is one of the risk factors for hemorrhage, especially in a low-resource setup, where the nutritional deficiencies are common.

The need for blood transfusion decreases after introduction of neat dissection technique – Birds' picking seeds' technique.

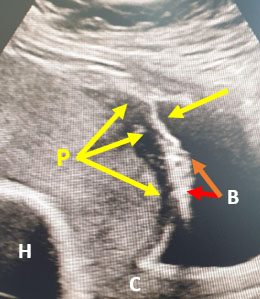

This technique is introduced to avoid blunt and sharp tissue dissection either in normal anatomy or in case of adhesion and fibrosis, it depends on the usage of monopolar diathermy and dissection piece by piece and in millimeters at the sites of placenta vascularity and the posterior bladder wall at the pocket of the placental invasion (Figure 3). This site later after clearance of the placental tissues will be overlapped and obliterated by the cervical cuffing when the uterus is preserved successfully or will be the stump site either in subtotal hysterectomy or in the case of total hysterectomy (Figure 4).

3

Anterior uterine wall and adhesion sites' dissection (A) and separation of the urinary bladder downward keeping the placenta invasion and bulging free from surroundings (P).

4

Specimen of cesarean hysterectomy after classical cesarean section site (A); dense adhesion sites between the anterior uterine wall, posterior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall and the urinary bladder (B); ballooning and bulging by placental invasion sites through the defect lower uterine segmant (C); and the cervix of the uterus (D).

Induction of general anesthesia followed by proper patient position and routine theater policy for time out is crucial. Surgery starts by midline longitudinal incision then the wound can be extended above the umbilicuis dependng on adhesion and exposure need. Midline incision gives a roomy space to perform the surgery with all options.

The following anatomical landmarks should be well identified:

- Margin of urinary bladder.

- Ovaries.

- Fallopian tubes.

- Ovarian ligaments.

- Infundibulopelvic ligaments.

- Tubo-ovarian ligaments.

- Round ligaments.

- Broad ligaments.

- Utro-sacral ligaments.

- Ureteric courses.

Adhesions may obscure the anatomy; the art of dissection is approaching from lateral to midline and helps to make the way easy for some orientation and anatomical marks' identification.

Proper mapping and replanning is key for the surgery course, reviewing all possible options for reservation of the uterus with minimum risk and to avoid hysterectomy if possible.

Two important steps before uterine incision:

- The decision is for the surgeon to select the suitable approach whatever the choice; release of adhesion is extremely of great important.

- Then the decision and performance of uterine arteries' ligation is a crucial step immediately before delivery of the baby matter: a maximum of 1 min between the last suture and baby delivery.

Options for uterine incision:

- Upper segment and classical cesarean section/tubal ligation.

- Low vertical longitudinal incision.

- Lower segment at the margin of the placenta possibly away from the invasion sites; focal or mass invasion. This incision is through the defected wall and delivering the baby with marginalization of the placenta, which is a little bit of a bloody field, re-evaluating the dissection and trimming the defect site as it will come later.

After delivery of the baby and being handed to midwife, clamping of the cord followed by proper double knotting and short length gives the chance of spontaneous placental separation and expulsion if no serious bleeding otherwise acts accordingly.

Uterotonic agent − Oxytocin 5 IU slowly intravenously followed by 40 IU in 500 normal saline infusion at a rate of 125 ml per hour; this step is simultaneously with cord clamping.

Meanwhile, closely observe for bleeding or signs of separation of the placenta and the possibility of removal of the placenta with no/less morbidity and less blood loss.

Anterior division of the internal arteries' ligation is one of the main options here that can be performed early during the surgery if uterine arteries' ligation is not enough to secure the bleeding. Two approaches are considered:

- Posterior approach entry to the peritoneum down lateral to the uterosacral ligament and away from the ureter.

- Anterior approach entry by round ligament division and downward to the pelvic wall to the anterior division of the internal artery.

Dissection of the bladder and separation of the possible seen adhesions using Birds' picking seeds' technique gives a neat clear surgical field and the urinary bladder is away and safe. This needs meticulous tissue handling, making use of electro- diathermy, mainly the monopolar diathermy and small mosquito artery forceps (Figure 5).

5

Mosquito artery forceps and monopolar electrothermy are the for birds picking seeds technique.

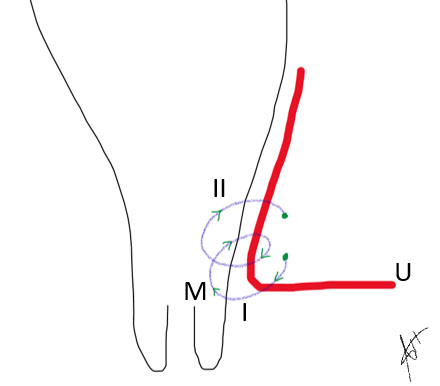

Lateral dissection from the round ligaments and parametrium is a reasonable approach that has less complications to free the adhesion and release the urinary bladder and further to skeletonize the uterine arteries for proper ligation with Vicryl 1 in a double suturing manner from lateral to medial, keeping the ureteric course under direct vision engulfing the artery and catching some myometrium tissues from the posterior side; this is the first turn then the second turn with the same technique followed by a gentle tie under direct vision with surgical knotting (Figure 6). At this step, check the ureteric courses and make sure the amount and color of the urine is acceptable because ureteric injury is one of the expected complications in MAP/PAS.

Full protection of the bowel should be away from the surgical field by packing the abdomen using large abdominal gauzes. Protection of the dissected urinary bladder should be provided with a bladder retractor. A self-retain retractor gives good pelvic exposure, it needs to be released in between and not tightly fixed to avoid femoral nerve accident.

6

Demonstrates the uterine artery (U) ligation in two turns. (I) and (II) from lateral to medial in a cross manner engulfing the myometrium (M).

In case the lower segment was already opened, fix soft clamps (designed locally by long artery forceps covered by pieces of Folly’s urinary catheter) (Figure 7). These clamps placed at uterine incision angles from anterio-lateral to posterio-medial direction decrease the blood flow and keep the ureter safe from being crushed at the time of bleeding till proper anatomical orientation and reasonable hemostasis. Uterine arteries' ligation will secure the main blood supply and makes the field clear to continue the surgery as planned, if this was not done from the beginning.

7

Soft-clamp long artery forceps covered by a rubber piece of Folly’s catheter.

The lower uterine segment, which is already occupied by the invaded placenta in a focal or mass manner, will be well exposed. The site of the placenta should be gently packed by an abdominal gauze soaked with warm normal saline and changed and replaced every now and then till complete repair of the uterine wall defect.

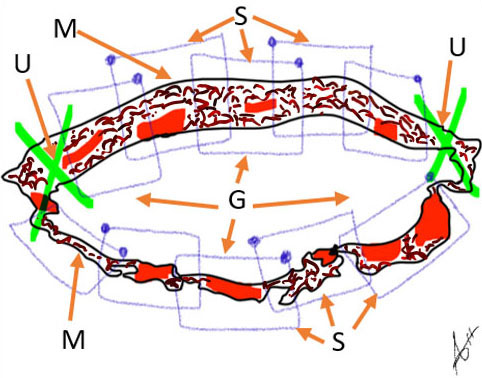

Focal resection or mass resection of the defected wall will be performed to close the available margins in a chain-block-like suture (Figure 8).

8

Diagrammatic representation of the incision margins at the lower uterine segments (M) with bilateral clamping of uterine arteries (U) and packing of the cavity with abdominal gauze (G) along chain-block suturing (S).

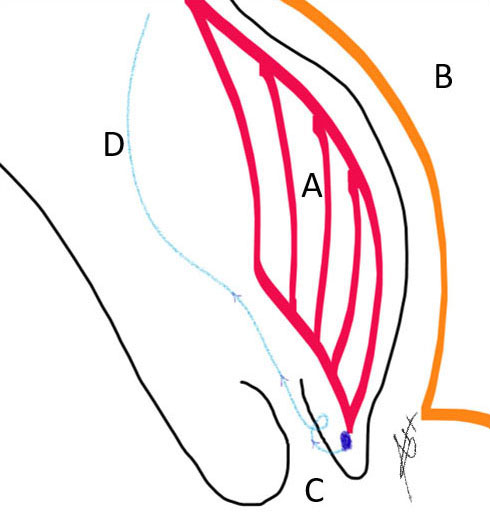

The resection usually followed by fine trimming of the margins with good hemostasis is mainly at the upper lip of the wound because the lower lip of the wound has the main defect of wall thickness if not completely absent. Here we make use of the cervical cuffing technique to support and strengthen the lower lip of the wound and obliterate the cave at the depth of the cervical stroma, which was occupied by the placental tissue making the defect towards the posterior urinary bladder wall, which is carefully dissected (Figure 9). This space was created by the placental invasions and after removal of the placental tissues the cave will be obliterated by the cuffing technique using a smooth fine needle most probably the suitable one is Vicryl 2/0 in an interrupted manner from down to up starting from in half a circle from 3 o'clock to 9 o'clock then from 9 o'clock to 3 o'clock around the circle of the uterine cervix, which secure the oozing and bleeders from the base and the margins (Figure 10).

9

Placenta localization (A) posterior to the urinary bladder (B) down in the uterine cervix (C) and the suture material at the site of cervical cuffing (D).

This cuffing of the anterior cervical lip with the remaining tissues and adhesion around the bladder at the vesico-uterine pouch gently will be approximated and form the lower margin of the lower uterine segment incision along with clear upper margin of the incision the lower uterine segment will be repaired and closed. There is some defect of wall thickness.

10

Diagrammatic representation of the cervical cuffing where the suturing (S) starts from the cervical lips (C) after eversion up-inwards to support the lower uterine segment and stop the bleeder from the placental invasion site towards the urinary bladder wall (B).

The suitable technique is the surgeon’s choice, which is quite enough to support the space can be performed.

During surgery, filling of the urinary bladder with normal saline through Folly’s catheter is a good practice step for urinary bladder integrity.

Review of the anatomy, making sure of no bleeding and the drain tube is usually kept and observed, mostly within 48 h it is dry and removed.

Some landmarks with non-absorbable sutures as knots usually kept as a guidance for the future surgery as most of the cases are keen for planned future pregnancy.

Non-absorbable suture material is used in wound closure specially for the rectus sheath and skin closure.

The iodine solution − Betadine − is the preferable solution for scrubbing of the surgery site as well as for wound dressing.

Following full recovery, the patient will be shifted to an observational room − like a high-dependent unit with simple vital signs' monitoring for at least 24 h then to a general room following post-operative care:

- Antibiotics.

- Analgesia.

- Thromboprophylaxis.

- Urinary catheter care.

- Wound dressing.

- Psychological support and case explanation.

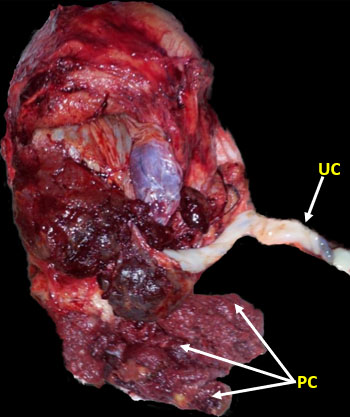

Ideally the placenta specimen, which usually has some wall remains should be sent for histopathology and almost this service is beyond our scope at present, although it is recommended in good practice. Macroscopic assessment is usually enough (Figure 11). Histopathology was required in selected cases, the specimen was sent to the nearby cities where some histopathology laboratories are available.

11

Specimen of MAP/PAS after successful complete removal. Umbilical cord (UC) and placenta cotyledons (PC).

Good and detailed informative education for the patient will be provided about the surgery course and the post-natal period and the future.

Good documentation is hand-written with diagrammatic representation of the anatomy, surgical steps, landmarks of adhesions, or any occuring complications like urinary tract injury.

Comparing the ideal meaning of Accreta Center of Excellence where MAP/PAS are managed most, and such models are used in the developed world and the work performed in developed and highly well-equipped facilities. Table 1 shows the ideal criteria for the center of excellence in comparison with the setup where most of our surgeries were performed.

In low-resource facilities, guidance and a practical point as protocol helps in management of MAP/PAS as follows:

- Accurate diagnosis is the first step.

- Appropriate surgical expertise is critical for MAP/PAS care.

- Anesthesiologist/anesthesia technician experienced obstetric hemorrhage with monitoring of vital signs, oxygenation, urine output, serum electrolytes, hematocrit, and coagulation status using a simple technique like a plain test tube test-poor man test.

- Trained specialist is the main responsible physician.

- Experienced transfusion technician helps and facilitates blood transfusion and makes use of blood-bank resources and alternatives.

- Preoperative consultation and evaluation should be performed.

- Utilizing surgical technologists and circulating nurses expert with MAP/PAS is extremely helpful, as with any specialized surgical procedure and arrangements should be made to have the appropriate equipment available.

- Postoperative care with proper monitoring and special preventive care for early complications:

- Fluids' management to avoid cardiopulmonary complications like pulmonary edema and atelectasis is important.

- Infection prevention.

- Thromboprophylaxis.

- Patient blood management to prevent and treat anemia.

- Psychotherapy for such morbidity that precipitate for post-traumatic stress.

1

Comparison of the ideal center of excellence with the situation in a low-resource set up. The first column (bold borders) is the suggested criteria for Accreta Center of Excellence.7

Suggested criteria for Accreta Center of Excellence | Low-resource setup | Comment |

1. Multidisciplinary team | Coordinated staff of one or two disciplines | |

a. Experienced maternal−fetal medicine physician or obstetrician | Obstetrician and gynecologist | |

b. Imaging experts (ultrasound) | Technician | |

c. Pelvic surgeon (i.e., gynecologic oncology or urogynecology) | Obstetrician and gynecologist | |

d. Anesthesiologist (i.e., obstetric or cardiac anesthesia) | Specialist anesthesia/senior technician | |

e. Urologist | Not available | |

f. Trauma or general surgeon | Available | |

g. Interventional radiologist | Not available | |

h. Neonatologist | Not available | |

2. Intensive care unit and facilities | Separate room supervised and run by trained nurse with basic vital signs monitoring and agreed local protocol | |

a. Interventional radiology | Not available | |

b. Surgical or medical intensive care unit | Not available | |

i. 24-h availability of intensive care specialists | ||

c. Neonatal intensive care unit | Available | Facility is cope with needs |

i. Gestational age appropriate for neonate | ||

3. Blood services | Run blood-bank technician blood availability on demand case by case in MAP/PAS mainly depends on mobile donors | |

a. Massive transfusion capabilities | ||

b. Cell saver and perfusionists | Not available | |

c. Experience and access to alternative blood products | Not available | |

d. Guidance of transfusion medicine specialists or blood bank pathologists | Not available |

CONCLUSION

Morbid adherent placenta (MAP)/placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is one of the most morbid conditions, which poses dramatic risk for massive obstetric hemorrhage along with serious complications such as consumption coagulopathy, multisystem organ failure, and maternal mortality. The best and first step in dealing with MAP/PAS mandates setting clear strategies for early diagnosis, referral, patient selection, follow up, care, and management. The surgical management choices may be considered according to available expertise, and geographical and individual circumstances. Preoperative assessment and counseling, intraoperative technique and plan of care, and postoperative follow up and education is the pillars for successful outcome.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Increase the awareness of early notification of pregnancy in women with previous scar and booking. Early notification facilitates diagnosis of scar pregnancy and helps in subsequent management of scar pregnancy as associated risk for MAP/PAS.

- Special advanced training ultrasound for perfect scar pregnancy diagnosis, placenta previa, and MAP/PAS.

- Adequately train future experts in the care of MAP/PAS.

- Provide continuous support for skills' improvement by supervised training, clinical applied anatomy courses, live demonstration by experts, and videos recordings of such surgery.

- The optimal skills needed to perform these tasks are best developed with repetition and experience.

- Improvement of hospital setup and standards of care to match diagnostic needs, safety, and outcome.

- High governmental and political commitment are required towards maternal health and women wealth to work on risk factors to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter and have received no financial support specifically in order to write the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Jauniaux E, Chantraine F, Silver RM, Langhoff-Roos J, FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Epidemiology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;140:265–73. | |

Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity asso- ciated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1226–32 | |

Calì G, Ggiambanco L, Puccio G, et al. Morbidly Adherent Placenta: Evaluation of Ultrasound Diagnostic Criteria and Differentiation of Placenta Accreta from Percreta. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2013;41:406–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12385. | |

Fazari A, Aristondo M, Azim F, et al. Methotrexate in Management of Morbidly Adherent Placenta. Clinical Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2019:91–4. | |

Babaei MR, Oveysi Kian M, Naderi Z, et al. Methotrexate Infusion Followed by Uterine Artery Embolisation for the Management of Placental Adhesive Disorders: A Case Series. Clinical Radiology 2019;74:378–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2019.01.006. | |

Jauniaux ERM, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, et al. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management. BJOG 2019;126:e1–e48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15306. | |

Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Expert Reviews, Center of excellence for placenta accreta; Patient Safety Series. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)