This chapter should be cited as follows:

Chandrasekaran M, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416553

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Assessment and Immediate Care of the Neonate

First published: November 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Assessment of a neonate may be slightly different from older infants or children regarding its examination structure and comparatively small size. However, the principles by which we assess a neonate remain the same. It must flow chronologically with background history first, and then systematic examination. The history should include familial predispositions to disease, maternal status, the course of pregnancy, and the nature of labor and delivery. The assessment also requires an understanding of the outcome of intrauterine and intrapartum experience and knowledge of extrauterine adaptation and the impact of hypothermia. Furthermore, the comprehension of the relation of physical findings to the time of their occurrence is vital. Assessment soon after birth is needed to ascertain whether there is illness or malformation. The next consideration is to evaluate for the minor abnormalities that are often discerned in otherwise normal infants. These findings must be identified as insignificant, transient, or normal variants.

Newborn resuscitation, including APGAR scores immediately after birth, which includes immediate assessment, is covered elsewhere in the GLOWM textbook (Immediate Care of the Newborn). The newborn assessment and examination, with specific issues of clinical importance, are discussed in detail in this chapter. The purpose of the examination is to identify significant, important anomalies that might impact on the health of the child in the future. It also represents an opportunity to assess and reassure parents about minor anomalies or normal variants. It is an important examination, and sufficient time must be set aside to undertake it thoroughly. While there is a focus on screening for conditions of the eyes, heart, hips, and testes, this chapter also deals with the general systematic assessment of the newborn.

BACKGROUND HISTORY AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON THE NEWBORN

Since some maternal, placental, or fetal conditions are associated with high risk to neonates, one must be aware and prepared to manage these infants accordingly (Tables 1–3). Risk factors such as intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), small for gestational age (SGA), and large for gestational age (LGA) all have associated clinical management challenges too. A systematic approach to collecting and recording the history is necessary (Table 1). Structured data systems, paper or electronic, can help to ensure that essential information is not missed. For the healthy newborn, history gathering at the time of the initial encounter after birth will emphasize the prenatal history (including maternal and family history), the delivery and neonatal transition, the initiation of feeding, and any symptoms or parental concerns that have manifested since birth.

1

Important aspects of maternal and perinatal history.

Family history Inherited diseases (e.g., metabolic disorders, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, polycystic kidneys, history of perinatal deaths) Maternal history Age, blood type/blood group sensitization Chronic maternal illnesses like hypertension, renal disease, cardiac disease, diabetes, bleeding disorders Venereal disease, herpes, or recent infections Infertility treatments Drug history – medications, drug abuse, alcohol/tobacco use Psychosocial situation if relevant Previous pregnancies (if applicable) Abortions/fetal demise/neonatal deaths Prematurity/jaundice/sepsis/respiratory issues Congenital malformations Breastfeeding Mode of delivery Current pregnancy Estimated gestational age Singleton or multiple Conception – spontaneous or assisted reproduction Prenatal care Results of any fetal testing (e.g., amniocentesis, ultrasound) Pre-eclampsia/gestational diabetes Bleeding Infection, use of antibiotics Polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios Glucocorticoids/magnesium sulfate Labor and delivery Presentation/mode of delivery Indication for cesarean section if available The onset of labor/duration of labor Rupture of membranes, intrapartum maternal fever Fetal monitoring Amniotic fluid (blood, meconium, volume) Anesthesia/analgesics Initial delivery room assessment (shock, asphyxia, trauma, anomalies, temperature, infection) APGAR scores, resuscitation details Placental examination/findings |

2

Neonatal complications associated with antenatal maternal characteristics, medical conditions, and previous obstetric history.

Maternal characteristics | Newborn complications | |

(1) Personal history | Poverty | Preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), infection |

Smoking | Increased perinatal mortality, IUGR | |

Drug/alcohol use | Fetal alcohol syndrome, IUGR, withdrawal syndrome | |

Malnutrition | IUGR, fetal demise | |

Age >40 years | Chromosomal abnormalities, IUGR, placental abruption | |

Age <16 years | Preterm, IUGR | |

(2) Medical history | Diabetes mellitus | Stillbirth, macrosomia, IUGR, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), hypoglycemia, congenital anomalies including heart and brain |

Renal diseases | Stillbirth, preterm, IUGR | |

Cardiac diseases | Preterm, IUGR, stillbirth | |

Thyroid diseases | Hypo- or hyperthyroidism | |

Anemia | Preterm, stillbirth, asphyxia, hydrops, IUGR | |

Urinary tract infection | Preterm, sepsis | |

Isoimmunization | Anemia, jaundice, hydrops, stillbirth | |

Thrombocytopenia | Bleeding including intracranial hemorrhage, stillbirth | |

Liver disease/cholestasis | Asphyxia | |

(3) Obstetric history | History of preterm, jaundice and RDS | Recurrence risk of same conditions |

Maternal fever | Infection/sepsis | |

Toxoplasmosis, other rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex (TORCH) infections | IUGR, microcephaly, rashes, brain injury, deafness, long term adverse neurodevelopmental outcome | |

3

Neonatal complications associated with placental and fetal conditions.

Characteristics | Newborn conditions | |

Placental anomalies | Small placenta | Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) |

Large placenta | Hydrops, maternal diabetes, large infant | |

Torn placenta | Blood loss, anemia | |

Abnormal attachment of umbilical vessels to placenta | Blood loss, anemia | |

Fetal characteristics | Multiple gestation | IUGR, twin–twin transfusion syndrome, preterm birth, asphyxia, birth trauma |

IUGR | Fetal demise, genetic abnormalities, congenital anomalies, asphyxia, hypoglycemia, polycythemia | |

Large for gestational age (LGA) | Congenital anomalies, birth trauma, hypoglycemia | |

Oligohydramnios | Fetal demise, renal agenesis, pulmonary hypoplasia, IUGR | |

Polyhydramnios | Anencephaly, omphalocele, neuromuscular disorders, trisomy, hydrops, anemia, intrauterine infection | |

Decreased activity | Fetal demise, asphyxia, neuromuscular problems | |

Abnormal fetal heart rate | Congestive heart failure, heart block, hydrops | |

Gestational age and birth weight classification

All neonates should be classified according to their birth weight and gestational age (GA), which correlates with the outcome. Tables 4 and 5 outline the classification according to gestational age and birth weight. The problems, management, and outcome depend on these factors.

4

Gestational age classification.

Gestational age | Classification |

Born less than 28 weeks | Extreme preterm |

Born between 28 and 32 weeks | Very preterm |

Born between 32 and 34 weeks | Moderate preterm |

Born between 34 and 37 weeks | Late preterm |

Born between 37 and 42 weeks | Term |

Born more than 42 weeks | Post-term |

5

Birth weight classification.

Birth weight (in grams) | Classification |

2500–4000 | Normal |

1500–2500 | Low birth weight |

1000–1500 | Very low birth weight |

Less than 1000 | Extremely low birth weight |

GESTATIONAL AGE ASSESSMENT

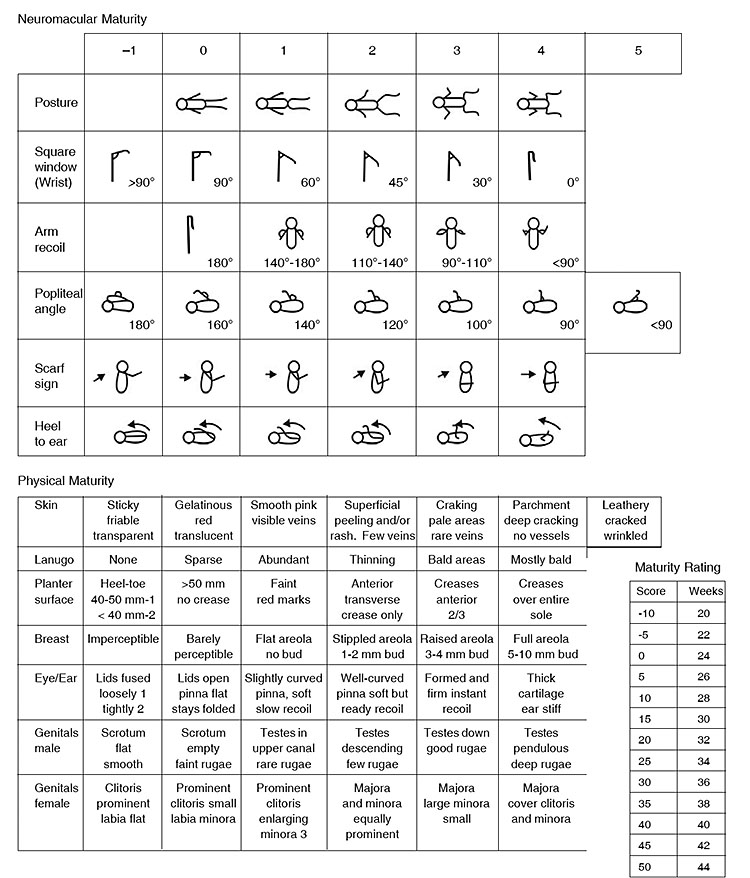

Gestational age (GA) assessment should be done for all neonates. GA estimates by first-trimester ultrasonography is accurate within 7 days. Second- and third-trimester ultrasounds are within approximately 14 and 21 days, respectively. Hence, to confirm obstetric dating, the modified Dubowitz (new Ballard) examination for neonates may be useful in GA estimation. The total combined score of neuromuscular maturity signs and physical maturity signs are to be taken into account. Ballard assessment of gestational age should be done during the first 24 hours of life and repeated at 48 hours of life. There are limitations to this method, and if the baby is hypoxic, acidotic, or has respiratory distress, the neurological assessment may be inaccurate. The examination must be repeated when the baby is stable later. Figure 1 gives the detailed maturity ratings.

1

New Ballard score for gestational age assessment.

GENERAL EXAMINATION

The general examination requires specific pediatric and neonatologist skills, which can be enhanced and fine-tuned throughout one's career. When one gets the opportunity to examine babies often, that person is more likely to come across different clinical presentations of a disease and, hence, obtain experience identifying problems early and managing the disease better. A healthy newborn examination involves a complete physical examination, including examining all parts of the body.

As a first step, care should be directed to determine the following:

- Any congenital anomalies that are present;

- Whether the infant has made a successful transition from the in-utero to the ex-utero environment;

- Any sign of infection or metabolic disease;

- Normal variations that may need little intervention, but reassurance for parents.

The baby should be naked from head to toe during the examination. Naked newborns are vulnerable to hypothermia, so they should not be kept uncovered for periods of no more than a minute or two at a time unless they are in or under a warming device. It is prudent to examine infants in a structured way (an order is suggested below) because they are quieter at the beginning when you need their cooperation. If the infant being examined is crying, it is important to soothe the baby first, e.g., short breastfeed/cuddle or brief swaddling.

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

The newborn's color is important to note as it is an important index of the cardiovascular system's function, indicating perfusion status. Normal color in Caucasian infants means a reddish-pink hue all over except for possible cyanosis of the hands, feet, and occasionally lips. The mucous membranes of dark-skinned babies are more reliable indicators of cyanosis than the skin. However, routine measurement of oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter is becoming the norm in high income settings. For a term infant, preductal and postductal oxygen saturations should be above 95% when measured around 24–48 hours of age to rule out any major congenital heart disease provisionally.

The heart should be examined with the limitations of this examination kept in mind. When the baby is peaceful, the rate, rhythm, and the presence of murmurs can be determined more easily. It is best to identify whether the heart is on the right or the left side. This is best done by auscultation but can be confirmed occasionally by palpation. The heart rate is normally between 120 and 160 beats/minute. It does vary with changes in the newborn’s activity, being faster when they are crying, active, or breathing rapidly, and appreciably slower when the baby has periods of slow breathing and is quiet. The presence of murmurs does not always mean significant heart disease in the newborn period. Infants can have severe heart anomalies without any murmurs. On the other hand, a closing ductus arteriosus may cause a murmur, which, in retrospect, is only transient but very loud. An innocent soft systolic murmur may be heard in about 4% of newborns in the first week. Most of these disappear in the first month. A definite and persistent systolic murmur seen after birth should be investigated with an echocardiogram. Referral for echocardiogram should be done in all cases with any of the following: a loud systolic murmur, any suspicion of abnormally placed heart, abnormally large heart on chest X-ray and absence of one or both femoral pulses (which may indicate outlet obstruction conditions like coarctation of the aorta).

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

The respiratory rate of a normal term infant is usually between 40 and 60 breaths/minute. However, all infants are periodic rather than regular breathers. This is more notable in preterm infants. Thus, they may breathe at a fairly regular rate for a minute or so and then have a short period of no breathing at all (usually 5–10 seconds). This is called periodic breathing and is benign. Apnea is defined as periods of no breathing for a minimum of 20 seconds; an infant's color changes from normal reddish pink to grades of cyanosis, which is not a normal phenomenon.

Respiratory distress can manifest in various ways. There should be no expiratory grunting in a normal neonate, little or no flaring of the outer parts of the nostrils (ala nasi) and no chest retractions (indrawing). If these features are present, then the infant is in respiratory distress. Tachypnea (breaths more than 60/min) can also indicate respiratory distress. Unless an infant has a severe central nervous system (CNS) depression, significant respiratory disease in the absence of tachypnea is rare. When crying, neonates display mild chest retraction; it may be considered normal. As a general rule, if the infant has good color and appears in no respiratory distress, the respiratory system is considered normal. Auscultation is rarely helpful when an infant is pink and breathing, without retraction or grunting, at a rate of fewer than 60 breaths/minute. Crepitations, decreased breath sounds, and asymmetry of breath sounds are occasionally found in the asymptomatic infant and may reveal occult disease, which can be confirmed by chest X-ray.

HEAD

The infant's skull should be examined for cuts or bruises due to either instrumental delivery or fetal monitor leads. Caput succedaneum is a benign condition, which is a diffuse edematous swelling of the scalp's soft tissues (present on the presenting part during vertex delivery) due to a collection of fluid, which may be mixed with blood. It usually covers one of the parietal bones but is not limited by suture lines. It is more obvious after prolonged labor, and it disappears in about 2 days. Cephalhematoma should be differentiated from Caput succedaneum. Cephalhematoma refers to a usually benign traumatic subperiosteal hemorrhage in the parietal region of the newborn skull. The swelling is usually not visible until several hours after birth. On palpation, the swelling does not extend beyond suture lines. If the infant develops jaundice, a periodic check of hemoglobin and serum bilirubin may be done to assess the extent of blood loss and an indication of phototherapy. However, most of these hematomas reabsorb in 2 weeks to 3 months, depending upon their size.

Mobility of the suture lines rules out craniosynostosis (defined as the premature fusion of cranial sutures). This is checked by putting each thumb on opposite sides of the suture and then pushing in alternately while feeling for motion. The degree of molding of the skull bones should be noted, and sometimes it may be considerable. Usually, this molding subsides within 5 days. Occasional infants have craniotabes, a shallow ‘ping pong ball’ indentation of the skull bones. The presence of craniotabes at birth may be suggestive of osteogenesis imperfecta or congenital rickets. Large fontanels reveal a delay in bones' ossification and may be associated with hypothyroidism and vitamin D deficiency. After molding has disappeared, the head is usually symmetrical, but there can be an unexplained tendency to turn the head more to one side than the other. This causes flattening and hair loss on one side of the occiput, with the opposite frontal region and face appearing to be prominent and stand out. The condition is called plagiocephaly. It tends to be noticeable at about the end of the first month. After that, it increases to maximum towards the ninth, after which it gradually becomes more symmetrical and is hardly detectable by the end of the second year.

EYE EXAMINATION

In the first 3 days of newborn life, puffy eyelids sometimes preclude examining the eyes at all. On the third day, usually the day of discharge, the eyes can and should be examined for the presence of scleral hemorrhages, iris coloring, and pupillary size, equality, and centering. The red reflex should be obtained to rule out cataracts. The newborn infant tends to keep their eyes closed much of the time, but a normal newborn can see, respond to changes in illumination, and fixate points of contrast for short periods. A persistent deviation of an eye in an infant requires evaluation.

Watering from one or both eyes may be noticed anytime following birth, usually after 3–4 weeks. The discharge of clean water is mostly due to a lack of normal drainage of lacrimal secretions into the nasal cavity. It is because of the developmental obstruction in the lacrimal passage. Gentle massage over the sac area three to four times a day should normally cure it for a few days. Eyes may be stick within the first 24 hours after birth without redness or swelling. It is sterile and requires no treatment. Later onset, especially when associated with redness and swelling of lids, usually means infection. Instilling antibiotic drops of choice every 2–3 hours for 2–3 days is usually curative. It is common to see some subconjunctival hemorrhages located near the eye's outer canthus in a normal baby. The blood gets reabsorbed after a few days.

NECK

The neck should be checked for the range of motion, thyroid swelling, and thyroglossal cysts. There may be a firm rounded mass in the sternomastoid muscle on either side in the second week of life or later. It is called torticollis. The child may keep the neck turned to one side all the time. It is probably due to a small hematoma from injury to the muscle at birth or a muscle fibromatous malformation. The majority of these tumors resolve spontaneously by 6 months to 1 year of age. The mother should be advised to overextend the affected muscle by turning the head in the opposite direction and flexing the neck toward the unaffected side, a few times a day over several days. If torticollis persists beyond 1–2 years of age, surgical correction may be undertaken.

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

The gastrointestinal system examination of a newborn infant includes from the oral cavity to the rectum and anus. This examination differs from that of older infants in that observation can again be utilized to a greater advantage.

Oral cavity

One may notice a few normal variations in the oral cavity. The mouth should be checked, and one should especially ensure that there are neither hard nor soft palatal clefts, no gum clefts, and no deciduous teeth present. Rarely, cysts appear on the gums or under the tongue. Epstein pearls are white pearl-like elevations, with one or a few appearing on either side of the median raphe of the hard palate. They are nothing but epithelial inclusion cysts and are of no significance. They usually disappear within a few weeks of birth. Tongue-tie or ankyloglossia is a minor abnormality seen at times on routine examination. It means tying the tongue to the floor of the mouth through a membrane or fibrous tissue. Mostly, there is only a thin, broad membrane in the midline. Occasionally, there can be a thick fibrous cord extending to the tip of the tongue and even grooving and limiting its upward movement. In such situations, when it is associated with feeding difficulty, the snipping of the tongue-tie may be done between 6 and 12 months of age, or sometimes earlier if it affects breastfeeding. It is never a cause of delayed development of speech. The eruption of one or more lower incisor teeth before or soon after birth occurs once in 4000 births. Such teeth tend to become loose and usually need extraction as they interfere with suckling and injure the breast. When loose, inhalation and aspiration into the respiratory tract may occur.

Abdomen

The anterior abdominal organs such as the liver can often be seen through the abdominal wall, as strong abdominal musculature does not develop until a few months after birth. The edge of the liver is also sometimes seen. When palpating the abdomen, start with a gentle pressure of the abdomen from lower to upper segments to reveal the edges of an otherwise unsuspected enlarged liver or spleen. The normal newborn liver extends up to 2 cm below the costal margin. Once the abdomen is observed and gently palpated, deep palpation is possible. Abnormal, absent, or misplaced kidneys should be felt on deep palpation.

The anus and rectum should be checked carefully, not only for patency but also for the position. Sometimes, large fistulas are mistaken for a normal anus, but careful inspection will show the fistula to be either anterior or posterior to the normal anus.

The umbilicus stump dries up and falls off between the sixth and fifteenth days of life. Sometimes excessive granulation tissue accumulates at the raw area left behind and shows up like a pink or red granuloma called an umbilical granuloma, which is always moist and does not heal with routine care. This may need one or more applications of silver nitrate stick or cauterization or sterile salt therapy (sprinkling of sterile salt on the granulomatous tissue). Umbilical hernia may be present in some newborns at birth. This is due to the umbilical ring's imperfect closure or weakness and is often associated with diastasis recti. It appears as a soft swelling covered with skin that protrudes during crying, coughing, or straining and can be reduced easily through the fibrous ring at the umbilicus. The hernia usually consists of the omentum or portions of the small intestine. Most umbilical hernias that appear during the newborn period will resolve spontaneously by 1 year of age. Therefore, the traditional treatment with a coin and bandage over the hernial site is not recommended.

The first stool (called meconium) is passed within 12 to 24 hours by most newborns, but rarely it may be delayed up to 48 hours of age, even in normal newborns. However, one should do a full evaluation if the baby does not pass meconium by 24 hours of age. Once feeding has been established, transitional stools are passed during the third and fourth days after birth. These are semi-solid in consistency and greenish-yellow in color. Thereafter, the newborns fed on breastmilk pass 2 to 6 golden yellow sticky, semi-solid, or even watery stools. Many babies pass stools while being fed or soon after due to an exaggerated gastrocolic reflex.

Regarding urine, the first urine may be passed during delivery in the labor room, where it often goes unnoticed. Thereafter, the newborn passes urine at any time in the first 48 hours. One-third of all newborns do not pass urine in the first 24 hours, and an occasional newborn may pass urine only at about 72 hours. Serious causes for delay in the passage of urine are rare in the absence of other clinical signs. However, during this period, the bladder area should be palpated to rule out any lower urinary tract obstruction.

EXTERNAL GENITALIA

The external genitalia of full-term newborn infants is quite different from those of slightly older infants. For males, the testis should be palpated on both sides. The testis is best found by running a finger from the internal ring (found in the mid-inguinal point, situated midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis) down on either side of the upper shaft of the penis, thus pushing and trapping the testis in the scrotum. One or both testes may not be in the scrotal sacs. When scrotal rugae are well-formed in a term child, they are usually retractile and can be felt a little above at a variable distance along the inguinal canal. They can be gently brought down into the sac on either side by holding the testes between the thumb and one or two fingers. Parents need to be reassured that testes will descend in their normal place in due course. The prepuce is normally nonretractile in all-male newborns and should not be diagnosed as phimosis. In the normal process of development, separation of the foreskin takes place gradually. It becomes fully retractile in 90% of boys by the age of 3 years. Phimosis, defined as the inability to retract the foreskin covering the head of the penis, is common in the newborn period. Hydrocoeles, defined as a fluid-filled sac in the scrotum next to the testicle, are not uncommon. They usually disappear in few weeks to months without being a predisposing factor for an inguinal hernia, unless they are communicating type. If present, the degree of hypospadias, in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis instead of at the tip, should be noted.

Female genitalia at term is most noticeable for their enlarged labia majora. Sometimes, a mucosal tag from the wall of the vagina is noted. No treatment is required for this. A discharge from the vagina, usually white in color is commonly found. The labia should always be spread, and cysts of the vaginal wall, an imperforate hymen, or other less common anomalies should be sought. The vaginal introitus may be imperforate with a thin septum covering it with margins meeting in the midline. Gentle traction from either side results in their separation. Menstrual like withdrawal bleeding occurs in many female babies after 3–5 days of birth and lasts for 2–4 days due to the withdrawal of maternal hormones that cross the placenta. Local cleansing and asepsis are indicated.

BREAST ENGORGEMENT

In some newborns, both males and females, engorgement of breasts may be seen soon after birth. On occasions, there is an actual secretion of colostrum. The enlargement often persists for several weeks. Therefore, any handling and pressing to express milk should be avoided, as it may lead to its longer persistence and development of infection and true mastitis.

SKIN

The epidermis of a newborn's skin is thin. The skin's common abnormalities include tiny milia on the nose, unusually brown pigmented nevi scattered around any area of the body, and Mongolian spots. They are described below.

Mongolian spots

The Mongolian spots are bluish, often on large areas, most commonly on the back or buttocks. Despite the name given to them, they do not have any relation with Down's syndrome. They disappear by 1 to 2 years of age but may take even longer. No intervention is needed.

Erythema toxicum

It is an erythematous rash with central pallor or vesiculopustular papules. It usually starts on the face within 1 to 3 days of birth and spreads on the trunk and extremities within 24 hours of its onset. It persists for about a week and is perfectly benign. No treatment is needed.

Milia

Milia are whitish, pinhead-sized spots that are tiny sebaceous retention cysts. They may be present at birth or may be noted any time during the first week of life. They are present mainly on and around the nose but singly can be present elsewhere on the face also. They only last for a few weeks and are of no consequence.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis

This is a benign condition of unknown cause and is characterized by three types of lesions: superficial small pustules, ruptured pustules with a central hyperpigmented macule, and hyperpigmented macules alone. The lesions are found at birth. The pustular phase lasts for about 2–3 days, and hyperpigmented macules may persist for as long as 3 months. No therapy is indicated.

Vernix caseosa

Vernix caseosa is a protective cheese-like greasy substance, covering the entire skin surface to a variable extent, from a thin layer just in folds and grooves, to extensive plaques all over the body in many newborns. It is more common in premature newborns and helps in maintaining the temperature by providing insulation. It dries up and peels off in the first 2–4 days, and no extra attempt needs to be made to remove it.

Lanugo hair

These are fine, sparse, and tiny hairs present in many infants over the skin surface. They usually disappear during the first month of life.

Salmon patches

Salmon patches are discrete, pinkish, capillary hemangiomas, 1/2 to 1 cm in size. These are located at the nape of the neck, upper eyelids, forehead, or nose's root. They invariably disappear after a few months without any treatment.

Strawberry hemangiomas

Strawberry hemangiomas are another common hemangioma. Typically, the baby is normal at birth, but at the age of 1 to 3 weeks is noted to have a red mark, usually on the face, scalp, or elsewhere. This increases rapidly for some weeks or even up to three months until a typical strawberry-or raspberry-like swelling is present. From the age of 3 months to 1 year, this nevus grows with the child. Finally, the color fades, and flattening occurs so that involution is complete at 7 or 8 years.

Acne neonatorum

Minute, profuse, yellowish-white papules are frequently found on the forehead, nose, upper lip, or term infants' cheeks. They denote hyperplastic sebaceous glands. These tiny papules gradually diminish in size and disappear within the first week of life.

SPINE

The infant should be turned over, and the spine, especially in the lower lumbar and sacral areas, should be examined. Try to look for pilonidal sinus tracts (narrow opening in the skin) and small soft midline swellings that might indicate a small meningocele or other anomalies. A dimple in the midline of the sacrococcygeal region can be seen in many newborn infants, and sometimes, it is deep enough to be mistaken for a pilonidal sinus. Even if a sinus is present at this site, it needs no treatment and disappears spontaneously in due course.

EXTREMITIES

Anomalies of the digits, club feet, and hip dislocations are common. Mild tibial bowing is normal. For checking for hip dislocation (if present, note that the femur's head gets displaced superiorly and posteriorly), place the infant's legs in the frog-leg position. With the third finger on the greater trochanter and the thumb and index finger holding the knee, attempt to relocate the femoral head in the acetabulum by pushing upward away from the mattress with the third finger and towards the mattress and laterally with the thumb at the knee. If there has been a dislocation, the femoral head's distinct upward movement will be felt as it relocates in the acetabulum. Hip "click", possibly due to the ligamentum teres movement in the acetabulum, should be distinguished from dislocated hips (hip “clunks”), which are much more common. Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) occurs in 1–2 per 1000 live births, with up to 20 per 1000 live births having unstable hips. Untreated DDH leads to abnormal gait, limp, and early onset of hip osteoarthrosis, causing early hip replacement. Treatment of DDH is effective. Neonatal screening for DDH is well-established in high-income countries and commonly practised in many low- and middle-income countries. When the neonatal screen for DDH is positive, the baby is referred for an ultrasound and orthopedic assessment. If DDH is confirmed, the initial treatment is with a Pavlik harness that holds the legs in the best position to support the growth of the acetabulum. The harness is used for several weeks or months. If the harness does not solve the problem, surgical approaches are likely.

NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION

The neurological examination will have to be performed carefully as it reveals any significant neurological problems present in the newborn. The symmetry of movement and posturing, body tone, and response to being handled and disturbed can all be evaluated while other parts of the body are being tested. The amount of crying should be carefully noted as well as whether it is high-pitched or not. When the baby is crying, seventh nerve weaknesses should be looked for (the mouth's affected side does not pull down). Erb's palsy, if present, is usually revealed by the lack of motion of the arm. The arm is adducted and internally rotated, with extension at the elbow, pronation of the forearm, and flexion at the wrist.

To check for tone and reflexes:

- Put your index fingers in the infant's palms and obtain the palmer grasp.

- When you have obtained this, hold the infant's fingers between your thumb and forefinger and raise the infant's body by pulling them to a sitting position.

- Note the degree of head lag and head control. A crying infant often throws their head back in anger – if this happens then the baby should be held in a sitting position, and the trunk moved forward and back enough to test head control again.

- Let the trunk and head slowly fall back toward the mattress.

If you wish to test the Moro's reflex, just before the baby's head touches the mattress, pull your fingers quickly from their grasp, thus, allowing the infant to fall back the rest of the way. Usually, the Moro's reflex results.

Suckling and rooting can be checked by using your clean little finger. Touching the upper lip laterally causes most infants to turn towards the touch and open their mouth; the more vigorous and hungrier the infant, the more intense the rooting response. Placing your finger in the infant's mouth initiates a suckling response. Stepping (and placing) are probably reflexes of fetal importance. This stepping can be elicited by holding the infant upright with their feet on the mattress and then leaning the baby way forward. This forward motion often sets off a slow alternate stepping action. One part of the examination that might be of special interest is eye-opening, which is brought on when the infant is suckling or held vertically. A detailed neurobehavioral examination should be done for all infants with suspected abnormalities.

WEIGHT LOSS

Under normal feeding conditions, a normal newborn tends to lose weight over the next 5 to 7 days of age. After that, it usually does not exceed 2% of birth weight daily, and total loss is not more than 10% of the birth weight. Birth weight is regained between 10 and 14 days of age.

DISCHARGE EXAMINATION

At discharge, the newborn should be re-examined in addition to the physical assessment mentioned above and the following points considered:

- Heart – development of murmur, cyanosis, or cardiac failure

- CNS – the fullness of fontanel, sutures, activity

- Abdomen – any masses previously missed, stools, urine output

- Skin – jaundice, rashes

- Cord – infection

- Feeding issues and weight loss

A checklist of advice for parents is provided in Tables 6 and 7.

6

Checklist for discharge check.

System | Details |

Appearance | Check color, posture, activity, breathing behavior |

Skin | Check color and texture, birthmarks, rashes |

Face | Observe appearance and symmetry |

Nose | Observe for appearance and symmetry |

Eyes | Check for red reflex and squint |

Mouth | Check palate and tongue |

Ears | Check for placement, shape, and symmetry. |

Head | Examine skull size, shape and swellings and the cranial sutures should be palpated |

Neck | Check for masses in the neck and clavicle |

Heart | Check for murmurs, heart sounds, saturation, and color of mucus membranes |

Lungs | Observe respiratory rate and work of breathing |

Abdomen | Check umbilical cord. Note any abnormalities |

Genitalia | Check male infant's testes, hydrocoele and hernia. Inspect female genitalia |

Spine | Check for sacral dimple |

Upper limbs | Check for length, proportion, and symmetry, check for extra digits |

Lower limbs | Check for length, proportion, and symmetry, check for extra digits |

Hips | Check for clicks and clunks |

CNS | Check tone, behavior, movements, posture, and reflexes |

Growth | Measure head circumference, weight, and length |

Newborn screen tests | Hearing screen, blood spot as appropriate locally |

7

Checklist for discharge check.

Advice to parents Things to avoid Tobacco smoke is harmful to your baby's health and increases their risk of dying from cot death. Protect your baby by eliminating exposure of your baby to smoke by making your house and car smoke-free. Breastfeeding Breastmilk is the best milk for all newborn babies. Your breastmilk gives your baby all the nutrients they need for around the first 6 months. Sleep position at home Always place your baby on their back to sleep, even for naps. Place their feet to the foot of the cot and with head and face uncovered. Immunization Vaccinate your baby; this will protect them from diseases. Danger signs Seek medical assistance for your baby if you notice the following:

|

NEONATAL SCREENING

It is important to screen babies for conditions that are difficult to diagnose antenatally. There are three components of neonatal screening: physical examination, hearing screen, blood spot screen. A top to toe physical examination is traditional, done flexibly to adapt to the baby’s behavior. It is discussed in detail in the above paragraphs. A few components of the neonatal physical examination are useful screening tests. Hip examination, red reflex, and pulse oximeter tests are examples to screen for significant diseases, as explained earlier.

Hearing screen

Some cases of permanent hearing loss can be detected in the newborn period. In high-income settings, screening should be done with objective tests. In the UK, newborn hearing screening is conducted with otoacoustic emissions. This procedure involves playing clicks to the baby. A healthy cochlea responds by making noises that can be detected. Screen failure or an uncertain response leads to an automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) test.

Blood spot screen

In the UK, the newborn blood test is done about 5 days after birth. The diseases screened for are as follows: sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, congenital hypothyroidism, and six metabolic conditions: phenylketonuria (PKU), medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD); maple syrup urine disease (MSUD); isovaleric acidemia (IVA); glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1); homocystinuria (pyridoxine unresponsive) (HCU). This can be very useful in low- and middle-income countries too, and some have already started implementing the screening test nationally.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the assessment of a newborn includes detailed history taking and head to toe examination. In addition, one should be aware of differentiating complications from physiological variations. This will help in the proper management of the baby and the communication and reassurance of the parents.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Newborn clinical examination and assessment takes around 15–20 minutes and should be performed on all babies in a systematic and standardized way.

- This routine physical examination excludes obvious abnormalities and screens for other, less obvious conditions.

- The examiner needs to understand normal newborn appearance and behavior to detect abnormalities.

- Most serious congenital anomalies can be detected at birth or within a few days, provided the examiner is aware of these anomalies.

- Some significant abnormalities may not be detected in the immediate newborn period, particularly some congenital cardiac diseases. This is often due to the limitations of the newborn clinical examination rather than the technique of the examiner. Therefore, it is important to educate parents that not all abnormalities can be detected at the initial examination.

- It is also important to document all findings, both positive and negative.

- Screening for conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, congenital hypothyroidism, or congenital cataract facilitates early detection and treatment. This may prevent or greatly reduce the risk of permanent residual disability.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

FURTHER READING

Eichenwald EC, Hansen ARE, Martin CR, et al. Cloherty and Stark's Manual of Neonatal Care 2016:95–116. | |

Gleason CA. Avery's Disease of the Newborn 2011;9th edn.:277–340. | |

Ireland HS. The Newborn Clinical Examination Handbook textbook, 2018. | |

O'Brien JE, Rinehart TT, Orzechowski KM, et al. The Normal Neonate: Assessment of Early Physical Findings. Glob Libr Women's med, 2009. | |

Lomax A. Examination of the Newborn: An Evidence-Based Guide. E-Book, 2011. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)