This chapter should be cited as follows:

Newbold SM, Wright JT, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415663

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 15

The puerperium

Volume Editors:

Dr Kate Lightly, University of Liverpool, UK

Professor Andrew Weeks, University of Liverpool, UK

Chapter

Prevention and Management of Postnatal Complications

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Whilst there are a number of national/international guidelines1,2,3 on monitoring postnatal women, there are few guidelines on the management of postnatal complications, and limited information is available in published texts. Many complications can be avoided by a healthy skepticism about the normality of what we see. An attitude of watchful expectancy and early intervention when necessary, will allow prevention of a situation, that can rapidly get out of control, leading to tragedy for mother and baby. This chapter highlights ways to prevent and manage complications, and tips for dealing with difficult complications. Remember the saying “to fail to prepare, is to prepare to fail”.

PREVENTING INTRAPARTUM COMPLICATIONS

Intrapartum care

On first contact with the woman, whether this is in a facility or in her home, check that the pregnancy has been normal, with a single fetus and a longitudinal lie. Check blood pressure and fetal heart rate. Confirm regular uterine contractions and cervical dilatation.

The woman should be encouraged to mobilize and remain adequately hydrated, with an adequate calorie intake for a potentially prolonged labor, with sweetened drinks. A partogram should be started to monitor progress and a plan for action to be made if the alert line is crossed. Delay in cervical dilatation should alert one to the possibility of uterine inertia in a primigravida or a malpresentation, particularly in grand multiparas. Failure of cervical dilatation together with a rising fetal tachycardia is highly suggestive of obstructed labor (LINK to obstructed labor chapter). If labor is not progressive, transfer to an EMOC (Emergency Obstetric Care facility)4 should be arranged. For these women, urinary catheterization will allow measurement of urine output and ensure that retention is not a cause of delay. If there is a vertex presentation, and it is safe to do so, start an oxytocin infusion. If the woman is pyrexial or fetal membranes have been ruptured for more than 24 hours a broad-spectrum antibiotic should be started (see Table 1).

1

Antibiotic options: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)5 advice and alternatives that can be used in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where some antibiotics may not be available.

Source of infection | RCOG advised antibiotics Use if available | Alternatives |

Wound infection/ dehiscence | V + Cl or F + Cl or Cl + T or V + Cl | C or F + M or A + G + M |

Cellulitis | No advice | F or E or A + M |

Necrotising fasciitis (not RCOG advice) | P + G + Cl | C + G + M |

Bowel perforation | Advice from general surgeons | C + M or A + G + M |

Vaginal hematoma | No advice | C + M or A + G + M |

Infected perineum | No advice | C + M or E + M |

Endometritis | G +. Cl + Ci or Ce + M + G | C + M or A + G + M |

Mastitis (lactating) | F + Cl or V + Cl or Cl + T | F or E |

Mastitis (non-lactating) | As lactating | A or E + M |

Sepsis (no focus) | Cl + G + Me or Cl + G + M + Ci | C + G + M |

SBE | No advice | Start with A + G Take advice from microbiologists or cardiologist |

Retained vaginal swab | No advice | A or E + M |

Prolonged ROM | No advice | A or C + M |

A, ampicillin; C, cephalosporin; F, flucloxacillin; M, metronidazole; G, gentamicin; Cl, clindamycin; V, vancomycin; Me, meropenem; T, teicoplanin; Ci, ciprofloxacin; P, penicillin G; E, erythromycin; Ce, cefotaxime.

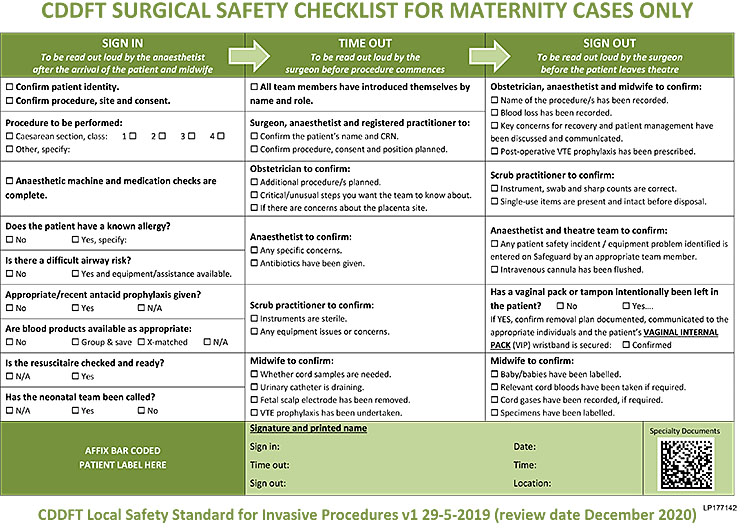

Safe surgical techniques

The aim of a cesarean section is to deliver the fetus safely, through the lower segment of the uterus, with minimal damage to the predominantly fibrous tissue of the lower segment and without damage to adjacent structures. With pre- and early labor procedures this can be relatively straightforward, but in situations where the presenting part of the fetus is impacted into the pelvis or there has been a previous cesarean section, or other surgery, the procedure can be very difficult. Having made the decision that a cesarean section is required, ensure that valid consent has been obtained from the woman (and her family where necessary). Before starting, ensure that there are the appropriate staff present, that there is enough equipment and sutures to proceed safely, and that there is adequate anesthesia. Check that the urinary bladder is catheterized and that there is urine draining, and use this opportunity to confirm that a vaginal delivery is not possible. Give the team a final briefing and address any issues raised on the WHO check list6 (Figure 1).

1

WHO check list.

Cesarean section for obstructed labor

Globally, cesarean section rates are rising rapidly, but in countries with a low cesarean section rate, these are more likely to be emergency cesarean sections for obstructed labor. These may be more challenging to perform and thus lead to more intra- and postoperative complications. This section looks at ways of minimizing these complications.

Open the abdomen through a transverse incision, not less than 2 finger breadths above the symphysis pubis. Enter the peritoneal cavity cautiously and as high (cephalad) as possible to minimize risk of trauma to the bladder. Remember, at full cervical dilatation with an impacted fetal head the bladder is likely to be high in the abdomen. The bladder catheterization may have been difficult because of pressure of the fetal head and it may be distended. If this is the case, empty it abdominally with a syringe and a needle before continuing with the procedure.

If there are adhesions between the bladder and the uterus or the bladder is very high in the abdomen, which is often the case in an obstructed labor, reflecting the visceral peritoneum and displacing the bladder can be difficult. In this case stop and make a high transverse incision in the uterus. The lower the head, the higher should be your uterine incision. In obstructed labor, especially if the cervix is fully dilated, place the incision at least 2 finger breadths above your planned site of incision. (You will still be lower than you think, a too low incision may be through the cervix). Enter the uterus in the midline, but extend the incision laterally, curving it upwards so that any tearing should remain visible and easier to repair.

If it is difficult to reach the vertex of the fetal head because the head is compressed against the symphysis pubis, try and pass your hand alongside the head laterally. Have someone prepared to dis-impact the head vaginally.

On delivery of the fetus and placenta, secure the angle of the incision with a figure-of-eight stitch to ensure hemostasis and then repair in the normal way. Uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage are common after cesarean section for obstructed labor, so immediately after delivery start a high dose oxytocin infusion.

Lateral extensions of the uterine incision

When there has been difficulty dis-impacting and delivering the fetal head or the incision has been low, extensions are common and may be associated with brisk bleeding and damage to the uterine artery complex, which is close to the ureter.

Temporarily control the hemorrhage by compressing the bleeding area. Place a single suture across the uterine wound where you can see it, and use this to apply traction medially, so as to rotate the uterus until you can see the extension and repeat the stitch until you reach and secure the angle.

Postoperative management

We recommend after a difficult cesarean section that all women should have an in-dwelling urinary catheter for 48 hours. If labor was obstructed, or dense adhesions had to be divided, the catheter should, however, remain in place for 10 days to reduce the risk of fistula formation. It is mandatory after any form of bladder repair. Postcesarean risk of infection is high, so treat with broad spectrum antibiotics for 7 days (given intravenously for at least 24 hours if clinical concern). Encourage early mobilization.

When the woman is ready, discuss the labor with her (and her family) and give advice on future deliveries). Ensure that a contraceptive plan is in place (Postnatal Family Planning). An IUCD can be safely fitted at cesarean section7 or depot progesterone contraception can be prescribed and has been shown not to reduce lactation. Contraceptive choices are reviewed by WHO.8

Care post symphysiotomy

Symphisiotomy, as a way of increasing the pelvic dimensions so as to allow vaginal birth in obstructed labor, is not commonly performed but can be very effective. The technique is described elsewhere.9

There is no specific care required postsymphysiotomy, although the Médecins Sans Frontières guidelines empirically suggest 7 days rest lying laterally with continuous urinary drainage for that time. There is no evidence that a pelvic binder is necessary. Women may need a walking frame for some days postprocedure and will possibly walk with a waddle if the pelvis remains unstable. The procedure may be associated with urethral and peri-urethral trauma which needs to be managed appropriately.

MANAGEMENT OF SPECIFIC POSTNATAL COMPLICATIONS

Women with postnatal complications usually present with a combination of pain, fever and feeling generally unwell. Diagnosis is based on history and examination, it is important that all the questions in Box 1 are asked. Examination should always include abdominal examination for tenderness, uterine tenderness and involution, distension, guarding or rebound and bowel sounds. Vaginal examination should be performed if lochia is offensive or heavy, to exclude a foreign body and to ensure that the cervical os is closed. Examination of other systems may be indicated if symptoms suggest a non-pelvic cause.

Box 1 Mandatory questions when assessing any postnatal woman with fever, pain or who is generally unwell.

- Number of days postnatal, mode of delivery, any complications at time of birth;

- When symptoms started, and whether continuous or intermittent;

- Site/nature/radiation of pain;

- Nature of lochia, is it heavy or offensive?

- Breast/urinary/bowel symptoms;

- Any other symptoms, e.g. dyspnea/dysuria, etc.

Some complications only occur after cesarean section, e.g. retained abdominal swab, some only occur after vaginal birth, e.g. vaginal hematoma, whereas many can occur after any birth, regardless of mode of delivery, e.g. endometritis. Some women may present in the postnatal period with problems that are not related to birth at all, e.g. TB. Possible differential diagnoses in these situations are listed in Box 2.

Box 2 Possible differential diagnoses in a woman presenting unwell in the postnatal period.

- After cesarean section:

- Abdominal wound hematoma &/or infection;

- Abdominal wound dehiscence;

- Cellulitis or necrotising fasciitis;

- Bladder laceration not repaired at cesarean section;

- Ureteric ligation;

- Paralytic ileus or colonic pseudo-obstruction;

- Swab or instrument retained in the abdominal cavity;

- Bowel perforation.

- After vaginal birth:

- Vaginal hematoma;

- Vulval hematoma;

- Retained vaginal swab;

- Infected or broken-down perineal repair;

- Bladder complications;

- Genital trauma.

- After any birth:

- Endometritis, with or without retained products;

- Constipation;

- Mastitis or breast abscess;

- Sub-acute bacterial endocarditis (SBE);

- Spinal abscess/meningitis after regional anesthetic;

- Nerve damage.

- Incidental:

- Appendicitis or any other non-obstetric acute abdomen;

- Previously unrecognised TB (more likely in HIV positive women);

- Chest infection (more likely after general anesthetic);

- Malaria.

Complications that occur only after cesarean section

Abdominal wound hematoma

Hematoma without infection is usually obvious within 24 hours of cesarean section, whereas wound infection without significant hematoma usually presents later, 3–10 days after surgery.

Hematoma only causes a very localized area of pain and bruising in the abdominal wall, which is very tender and tense. If the hematoma is sub rectus sheath, it may follow the outline of the recti. An infected hematoma, or wound infection usually presents with fever, localized pain and tenderness, localized erythema and possible cellulitis and/or discharge which may be clear or purulent. A tender fluctuant abscess may be palpable.

Investigations: full blood count (FBC) (especially white cell count (WCC)) and C-reactive protein (CRP), if available, may be helpful to monitor progress after treatment has started, but are not mandatory for diagnosis, which is usually clinical. A wound swab (if bacteriology available) is helpful if wound is discharging, and determines whether the infection is sensitive the antibiotics already given.

If a wound hematoma is tense or spreading, then surgical evacuation and ligating any bleeding vessels, with insertion of a wound drain and prophylactic antibiotics, is required. If the hematoma is not tense or large, it can be managed conservatively, but with prophylactic antibiotics. If there is a wound infection with a small fluctuant area, consider probing or aspirating the wound, to release pus or serous fluid. Consider formal surgical evacuation and debridement, if there is a significant infected hematoma or abscess. Clinically diagnosed wound infections should be treated with antibiotics, regardless of the need for drainage. Antibiotics, prophylactic or therapeutic, must cover Staphylococcus aureus (see Table 1). If the woman is clinically septic, start with intravenous treatment and change to oral when she improves. Antibiotics should be continued for 7 days.

Superficial wound breakdown

Superficial wound breakdown either associated with infection or hematoma formation will usually occur after 5–7 days and is associated with the discharge of pus, blood or both. Check with gentle digital probing that the rectus sheath remains intact, a defect in the sheath is dehiscence, which requires repair (see below.) For superficial wound breakdown, re-suturing is not normally required and the wound will heal by secondary intention. Initially the dead space in the wound may need to be packed with gauze and it may need to be kept clean by saline irrigation. Unless the woman is febrile or unwell antibiotic treatment is not usually necessary.

Wound dehiscence

Infection in the deeper layers of the abdominal wall, may lead to breakdown of the rectus sheath repair and wound dehiscence. Classically this occurs at about day 5 after cesarean section, and is not usually preceded by any significant maternal symptoms. Dehiscence does not occur until non-soluble wound sutures are removed, but delayed removal will not prevent this complication as the defect is in the sheath layer which requires surgical repair. Diagnosis is obvious as abdominal contents are visible. Immediate management should be to return the abdominal contents to the cavity and cover the abdominal wall defect with surgical swabs soaked in sterile water or saline – these can be held in place with either a waterproof dressing, clingfilm or by taping dry swabs over the wet swabs. Definitive treatment is debridement and repair of the defect under anesthetic, with broad spectrum antibiotic treatment for 7 days (see Table 1).

Cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis

It is very important to distinguish between cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis. Although they are both soft tissue infections with similarities in presentation, they have a very different clinical course. Cellulitis is a superficial skin infection usually spreading from the wound. It is commonly associated with a streptococcal infection or Gram-negative organisms that tend to spread. The diagnosis is made by the presence of erythema around the wound, associated with induration, which may be tender to palpation. Cellulitis is treated with antibiotics with good tissue penetration and careful observation to ensure that the swelling is not spreading rapidly (see Table 1).

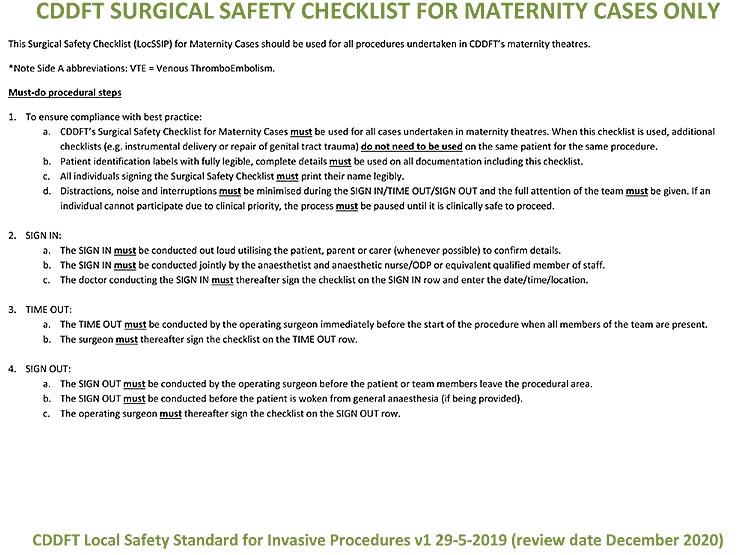

Necrotizing fasciitis is a potentially lethal infection of the subcutaneous tissue that, like cellulitis, can present with erythematous skin, swelling, fever, and pain. Significant pain (from necrosis in the deeper tissue layers) may be present before any other features are obvious. These earlier signs will be followed by bullae formation, skin sloughing, and tissue necrosis, as infection rapidly progresses (Figure 2). Necrotizing fasciitis requires urgent hospitalization, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (see Table 1), and early radical surgery. The surgical intervention can appear extreme as all necrotic tissue must be excised to a level where the wound starts to bleed. The tissues of the lower abdominal wall and the skin of the thigh and vulva may need to be denuded. The defect can be filled with a dry dressing and this can be kept in place with a dressing such as cling film. The edges of the dissection need to be checked carefully every few hours, if there is evidence that the infection is still spreading further surgical intervention will be necessary. However, this is life-saving surgery and only bold surgery will suffice. Inadequate excision may lead to the patient’s death. Patients are likely to need long-term surgical care with frequent replacement of dressings. They will suffer significant protein and fluid loss, which must be carefully managed with fluid replacement and a high protein diet.

2

Necrotizing fasciitis. Reproduced from Diab et al.,10 with kind permission of BMJ.

Closing the defects is beyond the scope of this chapter and will require referral to appropriate plastic surgeons. Even with appropriate plastic surgery, there is likely to be significant scarring which may lead to long-term contractures of the abdominal wall. It is likely that the denuded areas will also suffer from secondary infection.

Bladder laceration, late presentation

If a bladder laceration is not recognised and repaired at the time of surgery, then urine will remain in the peritoneal cavity and will cause deteriorating renal function. Waste products from the urine are absorbed across the peritoneum, causing rising serum urea and creatinine, with hyperchloremic acidosis. Women report vague generalized abdominal pain, distension and tenderness (may be mild), with general unwellness and a low-grade pyrexia within 48 hours of the surgery. Urine may start draining through the abdominal incision. As the symptoms are often vague, investigation is required to exclude a number of possible differential diagnoses. The diagnosis is usually made by abdominal/pelvic ultrasound which will show significant intraperitoneal free fluid. Abdominal X-ray (AXR) may help exclude other possible diagnoses. If available, arterial blood gases may help to both to diagnose and monitor progress. Ideally FBC, CRP and U&Es should be checked at diagnosis, and then serially to monitor recovery.

Initial management is urethral catheterization, with monitoring of blood tests. A small bladder laceration may heal with prolonged catheterization for 6–8 weeks. If the maternal condition does not stabilize or improve with conservative management, perform a laparotomy to repair the laceration. Identifying the urethral catheter balloon or instillation of intravesical methylene blue may help to identify the defect.

Ureteric ligation

If one ureter is damaged during cesarean section, and it is not recognised at the time, the woman may present in the few days after birth with unilateral loin pain and tenderness, pyrexia (UTI/sepsis) and general unwellness. The diagnosis is made by ultrasound scan which will identify unilateral significant hydronephrosis or free fluid in the peritoneum. The latter will occur if the ligature around the ureter causes necrosis and leakage of urine into the abdomen. If one ureter is tied, and the other kidney is functioning normally, it is likely that the woman’s renal function will remain normal. However, urine in the peritoneum will cause deteriorating renal function (see above re: bladder laceration, investigation and initial management is the same). If bacteriology services are available, send a urine sample (preferably from the drained hydronephrosis) for culture and sensitivities.

The initial surgical management of hydronephrosis should be percutaneous nephrostomy under ultrasound control followed, if possible, by ureteric stenting. If there is urine in the peritoneum, a laparotomy is required with ureteric repair, re-implantation or diversion. With all these procedures, careful on-going monitoring of maternal condition will be required, ideally with serial tests for infection and renal function (see above). It must be recognised that a second procedure may be required in a specialist fistula center.

Paralytic ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction

These complications usually occur 12–72 hours postcesarean section. They present in a very similar way, and it can be difficult to differentiate the two. Paralytic ileus (PI) is much more common than acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO), and usually resolves fairly rapidly with conservative management. ACPO, if not recognised, can lead to bowel perforation, usually of the caecum (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Both complications present with abdominal pain and distension, with associated nausea or vomiting. With PI, no flatus or stool is passed, whereas with ACPO the woman may report passage of some flatus or stool which may be diarrhea. There is no associated pyrexia with either PI or ACPO. With both conditions the abdomen is tense and significantly distended with generalized tenderness but no peritonism. Bowel sounds are absent or ‘tinkling’ with PI, but may be normal with ACPO. Management depends on assessment of the whole clinical picture.

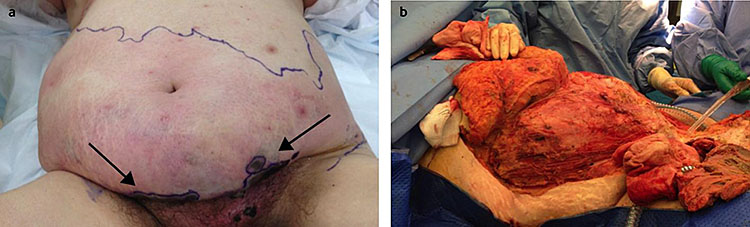

These conditions can generally be differentiated by performing an erect AXR. PI causes dilatation of loops of small bowel (greater than 3 cm in diameter), with fluid levels in these loops. ACPO causes large bowel and caecal dilatation (Figure 3), but small bowel fluid levels may be seen. Imminent bowel perforation is a concern if the colonic or caecal diameter is >9 cm. If available, contrast CT scan should be used to definitively diagnose ACPO and bowel perforation.

3

Erect abdominal X ray showing a dilated caecum and large bowel typical of ACPO. Free internet download.

Initial management of both conditions is conservative: nil by mouth, a nasogastric tube on free drainage, and adequate hydration with intravenous fluids (saline with potassium). The woman needs to be carefully monitored with 4 hourly vital signs and a careful medical review at least every 8 hours. A sudden deterioration in clinical condition probably indicates bowel perforation. Serial FBC (especially WCC) and CRP can also be used to monitor for infection. If ACPO persists, or bowel perforation occurs, both will rise. If symptoms persist, serum U&Es should be checked at least every 24 hours, as hypokalemia secondary to potassium loss into the dilated bowel may develop. Poor intravenous fluid management may also lead to hyponatremia and/or hypokalemia. Remember that at least 60 mmol KCl is required every 24 hours just to maintain normal U&Es (serum potassium 3.5–5.0 mmol/l) if the woman is not eating. More will be required (80–100 mmol KCl) if the pathology causes potassium loss.

If the diagnosis is PI, then clear oral fluids can be started once the woman has passed flatus and has bowel sounds. Diet can be subsequently introduced. ACPO can be managed conservatively for 24–48 hours, but if not improving follow the management in Box 3. Simply continuing conservative management risks bowel perforation. If, on review, bowel perforation is suspected, urgent laparotomy is mandatory.

Box 3. Management options for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction if not improving with conservative management. The best option in each case will depend on the facilities and expertise available.

- Medical (may not be an option in many low-resource countries):

- 5 mg intravenous neostigmine given over 5 minutes, which can be repeated once after 3 hours if no improvement;

- Possible side effects: vomiting, bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, excessive salivation;

- Do not give to women with heart disease or asthma;

- Ideally cardiac monitoring should be used during administration. A clinician must be immediately available for the 30 minutes after administration, and atropine and salbutamol nebuliser should be immediately available if needed.

- 5 mg intravenous neostigmine given over 5 minutes, which can be repeated once after 3 hours if no improvement;

- Endoscopic:

- Unprepared colonoscopic decompression with or without placement of a soft rectal decompression tube by a trained surgeon;

- Remember ACPO can recur after decompression, which can be repeated × 1;

- Remember flexible sigmoidoscopy is not an effective treatment.

- Surgical:

- Laparotomy by a general surgeon;

- Tube caecostomy or bowel resection.

Bowel perforation

Bowel laceration generally occurs at cesarean section, especially if adhesions have been divided. Ideally it should be recognised and repaired at the time of surgery. Unrecognised bowel perforation will usually present, with pain and fever within 36 hours of surgery, often earlier. This is often wrongly dismissed as simply postoperative pain. If diagnosis is significantly delayed, vomiting will occur, and the woman may become shocked. Abdominal examination reveals generalized tenderness with peritonism (generalized guarding and/or rebound), and bowel sounds may be absent, tinkling or even normal. Clinical diagnosis of an acute abdomen a few days postsurgery will require an urgent laparotomy – further tests are not necessary. If the diagnosis (or need for further surgery) is not clear, AXR (or CT) may be helpful; the absence of gas under the diaphragm excludes bowel perforation, but in the few days after cesarean section it can simply represent recent surgery.

If the pre-operative diagnosis is bowel perforation, broad spectrum antibiotics (see Table 1) and fluid resuscitation should commence immediately. Ideally laparotomy will be performed with the assistance of a general surgeon. A simple repair of the defect will not be adequate. Small bowel injury will require resection of the injured segment and end-to-end anastomosis. Large bowel injury will require resection with de-functioning colostomy.

Swab or instrument retained in the abdominal cavity

Although good checks, using swab counts and WHO check list,6 should avoid this complication, it must be recognised that retained swabs/instruments still occur with alarming frequency. Use of radio-opaque swabs aids the diagnosis of this complication, but non-radio-opaque swabs are still used in many countries and can be very difficult to identify on X-ray. Women with this complication can present in the early or late postoperative period. Presentation is generally with very vague symptoms such as abdominal pain, low grade pyrexia and feeling generally unwell. Examination generally reveals a vaguely tender abdomen, usually without a clearly demarcated area of tenderness and no peritonism. Bowel sounds are normal. Investigation is by AXR which will clearly identify metal instruments and radio-opaque swabs, non-radio-opaque swabs may not be visible, or may be visible as a vague mildly radio-opaque area. If the diagnosis is unclear after AXR, then perform an ultrasound which may identify a vague abdominal mass (which could be a swab or an abscess).

If a retained swab or instrument is identified, a laparotomy should be performed to remove the foreign object. This can be difficult, especially if the foreign object is identified some weeks after the cesarean section, as there will be fibrin adhesions to bowel and other structures. If the woman remains unwell, and the diagnosis remains unclear then a diagnostic laparotomy may be required. It would be wise to perform the laparotomy, if possible, with the assistance of a general surgeon, or with one on stand-by.

Complications that occur only after vaginal birth

Vaginal hematoma

Vaginal hematoma can occur with, or without, perineal trauma, as the hematoma occurs when para-vaginal vessels rupture as the vagina is stretched during birth. It presents with severe vaginal, vulval or buttock pain within a few hours of delivery. Perineal inspection may reveal a hematoma in the lower vagina (which may have an associated vulval component), or may be completely normal as the hematoma is higher in the vagina. One finger vaginal examination will reveal an extremely tense and tender vaginal swelling. Under anesthetic the hematoma should be incised, and the blood evacuated. An attempt should be made to identify the bleeding point, and tie it off, but often this is not possible. The ‘potential’ space can then be closed with an absorbable suture (but remember that this might allow the hematoma to reform) followed by closure of the vaginal wall with the same suture (use the heaviest suture available, e.g. 1 vicryl as fine sutures will tear the friable tissue). Alternatively, leave a corrugated drain in the paravaginal space and close the vaginal wall (as above). Remember to put a safety pin into the corrugated drain and attach it to a leg bandage. If the drain does not fall out, remove it after 48 hours. Give 7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics (see Table 1).

Vulval hematoma

Vulval hematoma occurs when a vessel continues to bleed despite perineal repair. It presents with severe perineal pain within a few hours of the repair. It is managed by removing the sutures, evacuating the blood clot, and re-suturing the perineum to close any potential dead space. It is advisable to use the heaviest absorbable suture available (e.g. 1 vicryl) to repair the muscle and vagina, as fine sutures will tear the friable tissue. Use a standard suture (e.g. 2/0 vicryl) for the skin repair. Antibiotic treatment is not required.

If a small relatively painless hematoma is found on perineal inspection a day or more after repair, no management is required, it will resolve naturally.

Retained vaginal swab

Swab checks (counting all swabs and tampons) before and after suturing, and not using small, easily retained, swabs for perineal repair should avoid this complication. However, it must be recognised that retained, swabs do still occur. Women with retained swabs usually present 7–14 days postnatal with either an offensive vaginal discharge, or having passed the swab material. It is important that a woman presenting with an offensive discharge is fully assessed as this can be the only presenting feature of endometritis (see below). Speculum and bimanual examination are mandatory (even if the woman has passed a swab) to take a bacteriology swab (if facilities available), and to remove any visible foreign object. It is important to also check that there is no foreign object retained in the vaginal fornices (two swabs could have been retained). After the swabs have been removed the woman should have 7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics (see Table 1).

Infected or broken-down perineal repair

This presents 7–14 days after perineal repair, with an offensive discharge. It may be associated with separation of the edges along part of, or the full length of, the skin repair. It is not usually painful. If bacteriology services are available take a swab. Clean the vulva with sterile water, or saline. Inspect the perineum, including digital probing of the wound to see if the muscle repair remains intact (which it usually is). If the muscle layer is intact then treat the infection with 7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics (see Table 1) and review after 5–7 days. The perineum should be left to heal by secondary intention, but re-suturing (generally only indicated for cosmetic reasons) should not be considered for a further 3 months.

If the muscle layer of the perineal repair is broken down, then the woman will require debridement and re-suturing under anesthetic. If re-suturing is required, the vaginal epithelium should be approximated in a single layer and muscles brought together to close any dead space but not too tightly as there is likely to be considerable perineal swelling and edema. It is advisable use the heaviest absorbable suture available (e.g. 1 vicryl) to repair the muscle and vagina, as fine sutures will tear the friable tissue. Close the perineal skin with individual stitches, which can have the knots inverted, to allow drainage of any fluid or hematoma.

Also treat the infection with 7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics (see Table 1).

Genital trauma

Genital trauma and its management is covered elsewhere in this textbook (Volume 12 Operative obstetrics).

COMPLICATIONS THAT CAN OCCUR AFTER BIRTH, REGARDLESS OF MODE OF DELIVERY

Endometritis, with or without retained products

Symptoms usually start a few days after birth and consist of pain, fever and offensive or heavy lochia,5,11 but may present with only one, or two of these. Abdominal examination reveals a bulky tender uterus (may feel boggy), without peritonism and normal bowel sounds. Vaginal examination reveals a tender uterus, and adnexae. It is very important to assess the dilatation of the internal cervical os. If the os is open, retained products are likely: if closed, then it is unlikely. Remember: retained products after cesarean section should be rare. The diagnosis may be clinically very clear. If it is not a pelvic ultrasound may reveal retained products, but remember it can be difficult to differentiate retained products and bulky infected decidua. A high vaginal swab (if bacteriology facilities available) may be helpful in case the woman does not improve with antibiotic treatment. If the woman is unwell, then serial FBC (especially WCC) and CRP can help monitor progress.

Endometritis should be managed with broad spectrum antibiotics, which must cover Gram positive and negative organisms (see Table 1). Start with at least 24 h intravenous treatment, and change to oral when the woman’s symptoms improve. Always complete 7 days of antibiotic treatment. If retained products are suspected on clinical examination, or ultrasound, then perform either manual vacuum aspiration or formal curettage under anesthetic, as well as antibiotics. Neither should be performed unless there is strong evidence of retained products as both procedures carry a risk of uterine perforation, and future Asherman’s syndrome, which can affect fertility.

Constipation

This is a common complication of pregnancy and the puerperium, which may be exacerbated by dehydration in labor and use of codeine containing analgesics. It may also be associated with a sore perineum. It is vital that serious postnatal complications are carefully differentiated from constipation, which is benign. Women with constipation may feel generally unwell with bloating, with no recent bowel movement but normal passage of flatus. Vomiting and pyrexia are not expected. Abdominal examination may be normal, or reveal mild abdominal distension, vague tenderness, but no peritonism. The descending colon may be palpable, loaded and mildly tender. Bowel sounds may be normal or increased. If the clinical diagnosis is constipation, investigations are generally not needed, but erect AXR may be needed to rule out more serious diagnoses. The AXR should only show a loaded colon. It should not show fluid levels, bowel dilatation or gas under the diaphragm.

Constipation should be managed with adequate hydration, normal diet and mobilization. If possible, stop constipating analgesia, and prescribe stool softeners/bulking agents such as bisacodyl (Dulcolax), Ispaghula husk (Fybogel) or macrogel (Movicol).

Bladder complications

Bladder complications after vaginal birth are covered in a separate chapter of this textbook (Postnatal Urological and Perineal Care).

Mastitis or breast abscess

Both these conditions are much more common in breast feeding women, but can occur without breast feeding, and can present in the early or late postnatal period.12 Both present with breast pain, which may be accompanied by fever. Mastitis is usually unilateral, but can be bilateral. It causes either the whole breast, or a section, to become red and swollen, and hot and tender to touch. There is no palpable mass with mastitis. Symptomatic relief is with simple analgesia and hot compresses. The woman should either continue to breast feed (from both breasts) or express milk, to avoid milk stasis. Mastitis in a breastfeeding woman is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, but in a non-breastfeeding woman (e.g. after stillbirth) could be caused by a number of organisms, requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics. Treatment is required for at least 10 days (see Table 1) because relapse often occurs after short courses of antibiotics. If there is a fluctuant tender mass in the breast tissue, indicating an abscess, then incision and drainage is required. Additional detail can be found in the chapter on Global Aspects of Breastfeeding.

Sub-acute bacterial endocarditis (SBE)

A transient maternal bacteremia always occurs after placental separation, this can lead to infection of a heart valve (SBE) in a woman with pre-existing valvular heart disease (e.g. mitral valve disease after childhood rheumatic fever). SBE does not occur in normal heart valves. This is a rare but potentially life-threatening postnatal complication. Women with previously unrecognised valve lesions could present with SBE in the postnatal period. Presentation usually occurs 2–14 days after the birth, but can be later. The mother will present feeling unwell, with a swinging pyrexia, but with no localized site of infection. Cardiac examination will reveal a heart murmur, which may keep changing in nature, and a hyperdynamic circulation, especially when the woman is pyrexial or tachycardic. Splinter hemorrhages may be seen in the fingernails, and fundoscopy may reveal optic disc swelling and areas of hemorrhage. SBE can be difficult to diagnose, and requires multiple blood samples for bacteriological culture; these should be taken during a pyrexial episode. Several samples are required because a single negative culture cannot rule out this diagnosis. If SBE is suspected, and transfer to a cardiac center is possible, then cardiac ECHO ultrasonography will confirm the valvular lesion, and may also reveal infected vegetations on the valve. Management requires 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics (see Table 1). If a woman is ill, and deteriorating, and SBE is suspected it is reasonable to treat on a presumptive diagnosis, especially if blood culture is not possible.

The management of sepsis in the postnatal period is covered elsewhere in the GLOWM textbook (Diagnosis and Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock in Pregnancy and the Puerperium, Puerperal Sepsis, Recognition of Maternal Sepsis, The Management of Maternal Sepsis).

Nerve damage

Most postnatal neurological problems are the result of pregnancy or labor, but a few are caused by regional anesthesia or surgery.13 Nerve damage usually presents with altered sensation and muscular weakness in the distribution of the damaged nerve, it occurs in approximately 1% of births, and most resolve spontaneously with time (which can be several months). Nerve damage is more likely to occur in first labors, with a prolonged second stage, obstructed labor or operative vaginal delivery. The fetal head can compress a number of nerve groups during labor pressure on the lumbosacral trunk can lead to foot drop, whereas pressure on the femoral nerve may affect hip flexion, or on the obturator nerve may affect hip adduction and rotation. There will also be sensory changes in the distribution of the affected nerve.

Obstetric nerve damage does not usually present with pain, whereas those associated with regional anesthesia usually do. Progressing symptoms imply changing pathology such as increasing compression from a hematoma or abscess. Symptoms of concern are listed in Box 4 and should prompt a very thorough neurological examination. If abnormal neurological signs are elicited an immediate MRI (if available) should be arranged to diagnose a central lesion. If a central compressing lesion is found urgent decompression (ideally by a neurosurgeon) is required to prevent permanent damage.

Box 4. Sinister postnatal neurological symptoms:

- Acute onset back pain;

- Leg pain in specific dermatome distribution;

- Urinary retention or incontinence;

- Anal dysfunction;

- Lower leg numbness and weakness.

Women with abnormal neurology should have active physiotherapy to retain limb movement, plantar splints may be required to prevent muscular contracture. Neuropraxia will usually resolve over weeks or months, but some women will be left with a permanent foot drop.

Spinal abscess/meningitis after regional anesthetic

Spinal abscess/meningitis after spinal or epidural anesthetic are extremely rare and usually present a few days after the anesthetic procedure. If they are suspected, investigation and management should be directed by a neurologist or physician. Epidural abscess presents with backache and signs of infection with spinal tenderness and a neurological deficit distal to the site of the abscess. It is managed by drainage of the abscess (ideally by a neurosurgeon) and intravenous antibiotics. Meningitis presents with fever, headache, neck stiffness +/− photophobia, the diagnosis is made by microscopy and culture of the CSF, and it is managed with intravenous antibiotics. High dosage of appropriate antibiotics should be administered as quickly possible; this should not be delayed whilst seeking further expert opinion.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Careful management of labor and good technique at cesarean section decrease the risk of postnatal complications. However, complications can still occur after a well-managed labor, and after vaginal birth.

- Women who present with pain, fever or feeling generally unwell must be thoroughly assessed to determine the cause of the symptoms.

- This requires a full clinical history, which must include details of delivery, details of the pain, assessment of lochia and determination of any associated symptoms such as breast, urinary, bowel or chest symptoms.

- Top to toe examination is always required including assessment of vital signs.

- Vaginal examination is always required if lochia is heavy or offensive, to elicit pelvic tenderness, sub-involution of the uterus and whether the cervical os is open.

- Appropriate management is determined by the clinical differential diagnosis. If surgical management is likely, early transfer to an appropriate facility should be undertaken.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Postnatal care. Clinical guideline 37. London: NICE, 2015. [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg37] ISBN 978-1-4731-0866-0. | |

The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists. Optimizing postpartum care. Committee opinion 736. Washington DC. ACOG. Obstetr Gynaecol 2018:131:140–50. | |

WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. Geneva: WHO, 2013. ISBN 978-92-4-150-664-9. | |

EMOC. Monitoring Obstetric Care, a hand book. WHO UNFPA UNICEF and Mailman School of Public Health. Averting Death and disability (AMDD) 2009. ISBN 978 92 4 154773 4. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Bacterial sepsis following pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No 64b. London: RCOG, 2012. [https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg64b/] | |

National Patient Safety Agency. WHO safe surgery checklist for maternity cases only. [www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/type/guidance/?entryid45=83972.2010] | |

Insertion of Intra-Uterine Contraceptive Device After Caesarean Section: A Systematic Update. In: Goldstuck N, Steyn P. (eds.) International Journal of Women’s health 2017;9:205–12. DOI: 10.2174/13WH.S132319. | |

Programming Strategies For Postpartum Family Planning. Geneva: WHO, 2013. ISBN 978-92-4-150649-6. | |

MSF: Essential Obstetric and Newborn Care. Paris, 2019; Section 5.7.1–5.7.7. ISBN 978-2-37585-039-8. | |

Diab J, Bannan A, Pollitt T. Necrotising fasciitis. BMJ 2020;369:m1428. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Postpartum haemorrhage, prevention and management. Green-top Guideline No 52. London: RCOG, 2016. [https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg52/] DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.14178. | |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mastitis and breast abscess. Clinical knowledge summary London: NICE, 2018. [htpps://www.nice.org.uk/mastitisand breast abscess] | |

Boyce H, Plaat F. Post-natal neurological problems. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2013;13(Issue 2):63–6. DOI: 10.1093/bjaccp/mks057. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)