This chapter should be cited as follows:

Samara A, O’Brien P, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419433

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 17

Maternal immunization

Volume Editors:

Professor Asma Khalil, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London, UK; Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Professor Flor M Munoz, Baylor College of Medicine, TX, USA

Professor Ajoke Sobanjo-ter Meulen, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Chapter

SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnancy

First published: May 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

As of 25 November 2022, approximately 13 billion COVID-19 vaccines had been administered globally, while there have been more than 636 million confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections and over 6.6 million deaths, reported to the World Health Organization. The exact number of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnant people is difficult to estimate; however, women of reproductive age (15–49 years old) constitute more than 20% of the global population. At any given time, approximately 5% of women of reproductive age are pregnant, so it is likely that several million women were infected in pregnancy during the COVID pandemic. This makes COVID-19 one of the most prevalent diseases in pregnancy of our times.

COVID-19 IN PREGNANCY: RISK FACTORS AND PERINATAL COMPLICATIONS

The prolific rate of publication in the medical literature since the start of the pandemic is a testament to the efforts made by clinicians caring for pregnant people and researchers involved in public health. A huge amount of research has sought to identify the risk factors for COVID-19 among pregnant and postpartum women, and to assess disease severity, including effects on maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Early studies, later confirmed by demographic and epidemiological systematic analyses, reported that pregnant patients are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease.1,2

Compared to non-pregnant women of the same age, pregnant patients had increased rates of hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, intubation, and death.3 A living COVID-19 systematic review reports higher rates of several adverse maternal outcomes and ICU admission (OR 2.61, 95% CI 1.84–3.71) and invasive ventilation (2.41, 95% CI 2.13–2.7) compared with non-pregnant women of reproductive age.4 Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 infected pregnant patients had significantly higher odds of death (6.09, 95% CI 1.82–20.38) compared to pregnant people without COVID-19. The most common clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in pregnancy were fever and cough (each 36%). Compared to pregnant women not infected with SARS-CoV-2, those with COVID-19 had increased odds of ICU admission (5.41, 95% CI 3.59–8.14), cesarean section (1.17, 95% CI 1.01–1.36) and preterm birth (1.57, 95% CI 1.36–1.81).

As documented from the early months of the pandemic, people with comorbidities were at greater risk of more severe disease and unfavorable outcomes compared to individuals without these comorbidities. A recent meta-analysis has reported that women with comorbidities such as pre-existing diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, were at higher risk of severe COVID-19 and adverse pregnancy outcomes compared with those without these comorbidities.5 This study also documented that women who were underweight pre-pregnancy were at higher risk of ICU admission (RR 5.53, 95% CI 2.27–13.44), ventilation (RR 9.36, 95% CI: 3.87, 22.63), and pregnancy-related death (RR 14.10, 95% CI 2.83–70.36). Pre-pregnancy obesity was also a risk factor for severe complications of COVID-19 including ICU admission (RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.26, 2.60), ventilation (RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.20–3.51), any critical care (RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.28–2.77), and pneumonia (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.18–2.33). An increased risk of ICU admission (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.25–2.11) and death (RR 2.36, 95% CI 1.15–4.81) was also correlated to anemia in pregnancies with COVID-19.6

The same meta-analysis identified all published maternal risk factors correlated to severe COVID-19; these included advanced maternal age, increased body mass index (BMI), any pre-existing co-morbidity, chronic hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and gestational and pre-existing diabetes. The risk factors associated with ICU admission included advanced maternal age, raised BMI, non-white ethnicity, pre-existing comorbidity, chronic hypertension, and pre-existing as well as gestational diabetes. Finally, the risk factors associated with the need for invasive ventilation and with maternal death included non-white ethnicity and high BMI.

Assessment of the perinatal outcomes of pregnancies affected by COVID-19 showed that the odds of stillbirth (1.81, 95% CI 1.38–2.37) and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (2.18, 95% CI 1.46–3.26) were also higher compared with those who had not been infected.7

TYPES OF COVID VACCINES USED IN PREGNANCY AND THEIR MECHANISM OF ACTION

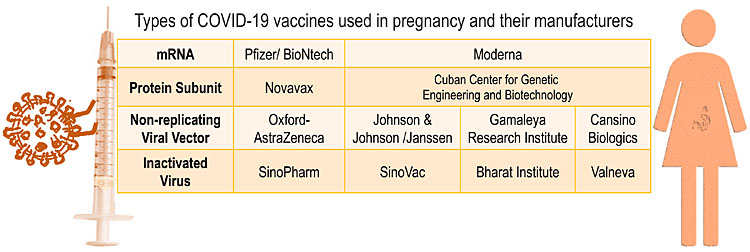

Three types of COVID-19 vaccines are currently available and used globally; a fourth (protein subunit) is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and awaiting approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Figure 1).

1

Types of COVID-19 vaccines used in pregnancy and their manufacturers.

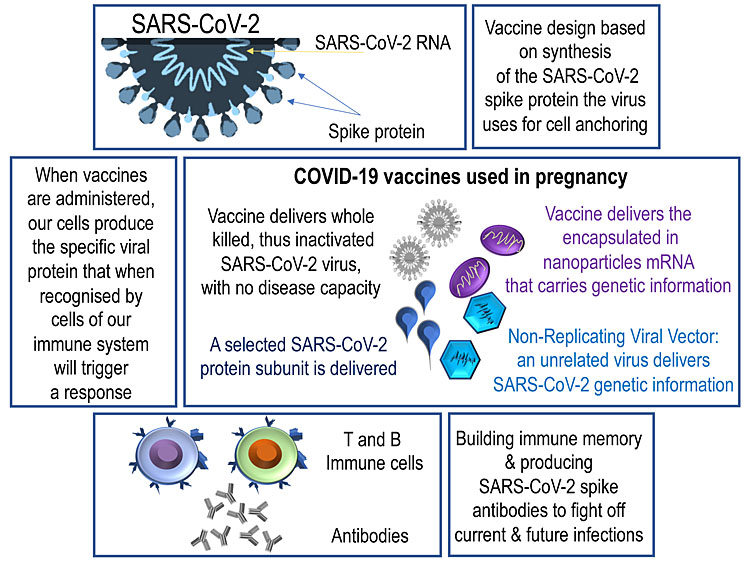

The COVID-19 mRNA vaccines demonstrated high vaccine efficacy in the initial vaccine clinical trials and given their safety profile, became the most commonly recommended and used vaccines in pregnant women. These vaccines convey mRNA particles that prompt the muscle cells in the injection area to initiate a cascade of events that eventually lead to the synthesis of a part of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Figure 2).

2

Vaccine synthesis.

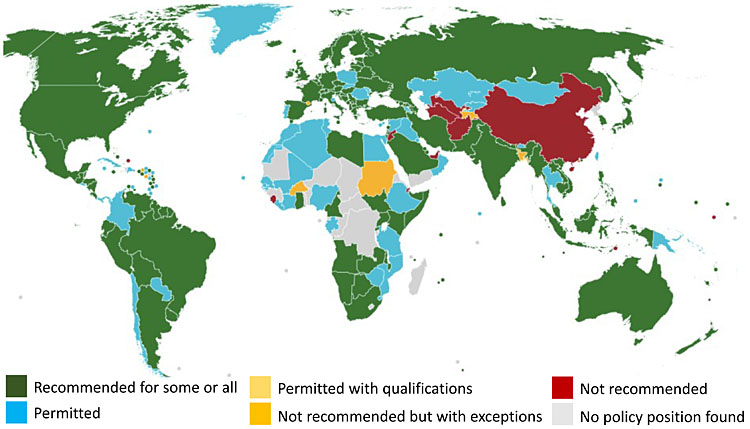

As mRNA vaccines have not been globally available, being the most expensive and of limited initial supply, viral vector and inactivated vaccines were also used in pregnant women. However, there were fewer safety data for the use of these vaccines in pregnant people. The United Kingdom and Canada public health authorities did not recommend viral vector vaccines for use in pregnant women; this was not because of any specific safety concerns, but simply because fewer data on their use in pregnancy were available compared with the mRNA vaccines. The CDC, on the other hand, did recommend the use of viral vector vaccines in specific cases (Figure 3).

3

Global COVID-19 vaccine policies on pregnancy (Policies as of Nov.2022. Source: COVID-19 maternal immunization tracker https://www.comitglobal.org/vaccines/matrix/pregnancy).

Systematic safety data collection and ongoing studies have shown that mRNA, viral vector and protein subunit vaccines are able to elicit cellular or humoral immune responses, including T cell and germinal center responses, and induce generation of memory cells, thus greatly improving their efficiency.

DATA ON EFFECTIVENESS OF COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PREGNANCY

When rollout of COVID-19 vaccines began in December 2020, there were no available data on COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy, as pregnant women had been excluded from the initial vaccine clinical trials that led to their approval for use (with the exception of the few women that became pregnant during the trials – in whom there were no adverse outcomes). Now there is a growing body of consistent evidence that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are safe during pregnancy.8,9 Data from US vaccine safety monitoring systems, such as the Vaccine Adverse Event Report System (VAERS), v-safe, the v-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry, and the Vaccine Safety Datalink, have not identified any safety concerns for vaccinated pregnant women or their infants.10,11,12

Other studies have shown that, in addition to being safe in pregnancy, mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are effective in reducing the risk of severe illness in pregnant people and the risk of COVID-19 hospital admission among their infants younger than 6 months.13,14 Moreover, the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to the non-vaccinated group was also documented in a large study from Israel,15 and the CDC and others have reported no increase in the risk of miscarriages.16

DATA ON REACTOGENICITY OF COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PREGNANCY

According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), studies of the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, involving more than 65,000 people at various stages of pregnancy, did not find any evidence that vaccination increases the risk of complications of pregnancy, miscarriage, premature birth or harm to the unborn baby.17 On the contrary, the data substantiated that vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization and death in pregnant people, similar to people who are not pregnant. In addition, vaccination has mostly mild or moderate side-effects, similar to those seen in vaccinated non-pregnant people, that recede within a few days.17

Furthermore, the results of a recent ongoing online prospective cohort study on COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant and lactating individuals (n >17,000), suggests that the third (or booster) doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were well tolerated among pregnant and lactating individuals18 (note: third dose for people who had completed their initial COVID-19 vaccine course more than 5 months after mRNA vaccination; booster for people more than 2 months after receipt of the Janssen vaccine). Most (1961/2009 [97.6%]) of the pregnant and lactating (9866/10,277 [96.0%]) participants reported no obstetric or lactation concerns after receiving a third/booster dose of the COVID-10 vaccine. In brief, 82.8% reported a local reaction, and 67.9% reported at least one systemic symptom. Compared with vaccinated people who were neither pregnant nor lactating, pregnant participants were more likely to report a local reaction to a COVID-19 third dose, but less likely to report a systemic reaction.

The Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network cohort study19 reported that vaccinated pregnant women had decreased odds of a significant health event compared to non-pregnant vaccinated females after both dose one and dose two of any mRNA vaccination. The same study also documented that overall, 4.0% of the vaccinated pregnant women reported a significant health event after dose one of an mRNA vaccine, and 7.3% after dose two, compared to 3.2% of the unvaccinated pregnant women. The vaccinated pregnant women had increased odds of a significant health event within 7 days of the vaccine after dose two of mRNA-1273, but not after dose one of mRNA-1273 or any dose of BNT162b2, and decreased odds of a significant health event compared with non-pregnant vaccinated females after both dose one and dose two of any mRNA vaccination.

SAFETY OF COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PREGNANCY

According to the findings of the CANVAS network cohort study, COVID-19 mRNA vaccines have a good safety profile in pregnancy.20 A single-center cohort UK study21 recruited approximately 1300 pregnant women who gave birth between March 1 2020, and July 4 2021 and reported that vaccination was not significantly associated with birth at <40 weeks’ gestation. Of those vaccinated, 85.7% received their vaccine in the third trimester and 14.3% in the second trimester of pregnancy. Almost 91% of those vaccinated received an mRNA vaccine and 9.3% received a viral vector vaccine. Using a propensity score–matched cohort, the rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes of 133 women who received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy were similar to those of unvaccinated pregnant women. More specifically, the study reported similar rates of stillbirth (0.0% vs. 0.2%), fetal abnormalities (2.2% vs. 2.5%), postpartum hemorrhage (9.8% vs. 9.0%), cesarean delivery (30.8% vs. 34.1%), small for gestational age (12.0% vs. 12.8%), maternal high-dependency unit or ICU admission (6.0% vs. 4.0%), or neonatal intensive care unit admission (5.3% vs. 5.0%). The investigators noted a slightly increased rate of intrapartum pyrexia, but this was not statistically significant after exclusion of the women with antenatal COVID-19 infection.

Even more importantly for the mother-fetus dyad, there is now good evidence that mRNA vaccination in pregnancy leads to robust maternal antibody response and that vaccine mRNA products do not cross the placenta at detectable levels, while vaccine-induced immunity (anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and neutralizing antibodies) are transferred transplacentally. It has also been shown that maternally derived vaccine-induced immunity can persist through early infancy; for this efficient transplacental antibody transfer it is crucial that the vaccination course is completed before the birth.22,23,24,25

VACCINE UPTAKE IN PREGNANCY AND VACCINE HESITANCY

Studies of other vaccines have shown that the two most critical factors affecting vaccine uptake among pregnant people is availability and offer of the vaccine, and its recommendation by healthcare providers;26,27 this was also observed in relation to COVID-19 vaccination.28 Because pregnant women were excluded from the early COVID-19 vaccine studies, national and professional institutions could not initially recommend the vaccine in pregnancy, until sufficient safety and efficacy data became available. This lack of healthcare professional endorsement, combined with the COVID-infodemic, has contributed to vaccine hesitancy among pregnant people, who were naturally concerned about any potential adverse effect, particularly on their baby.

Of note, Japan has one of the lowest levels of trust in vaccines worldwide,29 and during the COVID-19 pandemic the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among pregnant Japanese women, was higher than that in other countries, especially primiparous women.30

In a systematic review of 375 studies31 exploring factors affecting pregnant women’s decisions, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was nearly 50%. Lower rates of vaccine uptake were seen among participants from high-income countries (47%; 95% CI 38–55%) those with fewer than 12 years of education (38%; 95% CI 19–58%), and multiparous women (48%; 95% CI 31–66%).

A UK study32 found reduced vaccine uptake in younger women, women with high levels of deprivation, and women of Afro-Caribbean or Asian ethnicity compared with women of White ethnicity. Women with pre-pregnancy diabetes mellitus had increased vaccine uptake, while pregnant women of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity had a significantly lower antenatal vaccine uptake rate.33 Replies to an anonymous questionnaire in Italy, showed that highly hesitant pregnant respondents did not have a graduate degree, were less concerned about the risk of being infected by SARS-CoV-2, and those trusting mass media, internet sites, and social networks for information about vaccination against COVID-19.34

COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PREGNANCY IN LOW TO MIDDLE INCOME COUNTRIES

Healthcare professionals were among the most trusted sources of information on vaccination.35,36 A survey of pregnant women conducted in seven low- to middle-income countries (LMICs)37 in late 2021, documented that almost 50% believed that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for pregnant women, with around 57% of responders stating that if the vaccine was available, they would get vaccinated. Approximately 35% replied that they would decline, citing concerns around safety and adverse effects, and due to lack of trust in the vaccine. Those with lower educational status were less willing to be vaccinated. It has been reported that only a minority of pregnant women were vaccinated in India (12.9%) and Guatemala (5.5%).38 Similarly, a survey of pregnant women in Southwest Ethiopia had revealed that approximately 31% of the participants had an intention to be vaccinated when the vaccine would be made available in Ethiopia.39 In Cameroon, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and misinformation were highly prevalent among both pregnant and non-pregnant adults in 2021, when vaccines were available but still not recommended for use in pregnancy.40

This COVID-19 vaccine survey in LMICs found that levels of knowledge about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine were generally low but variable. Concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness among pregnant women are important issues to address with educational efforts to increase vaccination rates.

PROTOCOLS OF COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PREGNANCY AND BOOSTER DOSES

Recommended primary COVID-19 vaccination series consisted of two doses separated by several weeks’ interval for most vaccines. However, due to the limited supply of the vaccines in early 2021, not all countries followed the recommended interval between doses. The emergence of the new variants of coronavirus was associated with a decrease in vaccine effectiveness.

According to the CDC, 71.3% of pregnant women in the US received at least the primary COVID-19 vaccine series either before or during pregnancy, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) estimates that 55% have received a booster.41 The CDC guidelines state that people who are pregnant should stay up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines, which includes receiving a COVID-19 booster when offered.42

In December 2021 in the UK, it was recommended that all adults including pregnant women should get a booster (third dose) by the end of the year, and it could be administered 3 months after the second dose. Pregnant women were strongly encouraged to have the COVID-19 booster vaccination to enhance immunoprotection for both mother and baby. Vulnerable pregnant women without a competent immune system (organ or stem cell transplant recipients, primary or acquired immunodeficiency, etc.) sometimes required all three vaccine doses for their primary vaccination series, and booster shots would still be recommended 3 months after the primary vaccination series. Vulnerable, high-risk and immunosuppressed pregnant people were also invited for an extra ‘Spring booster’ in 2022, 6 months after their last dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

CONCLUSIONS

Studies have quantified the increased risk that both pregnant patients and their babies face if infected with SARS-CoV-2. Ongoing investigations provide very reassuring evidence around the safety of the COVID vaccines in pregnancy. Education about vaccine safety and clear communication by healthcare professionals to pregnant women is essential. Continued investigation and postvaccination epidemiological surveillance, reporting of safety data on pregnancy outcomes and infant follow-up should be at the top of the list of public health authorities, clinicians and researchers, to address vaccine hesitancy.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Compared to non-pregnant women of the same age, pregnant individuals have increased rates of severe COVID-19 disease, hospital admission, intensive care unit admission, intubation, and death.

- The COVID-19 mRNA vaccines demonstrated high vaccine efficacy in the initial vaccine clinical trials and given their safety profile, they are the most recommended and used vaccines in pregnant women.

- Three types of COVID-19 vaccines are currently available and used globally; a fourth (protein subunit) is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and awaiting approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- Systematic safety data collection and ongoing studies have shown that mRNA, viral vector and protein subunit vaccines are able to elicit cellular or humoral immune responses, and induce the generation of memory cells, thus greatly improving their efficiency.

- mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are effective in reducing the risk of severe illness in pregnant people and the risk of COVID-19 hospital admission among infants younger than 6 months; CDC and others have reported no increase in the risk of miscarriages after vaccination.

- Vaccination has mostly mild or moderate side-effects, similar to those seen in vaccinated non-pregnant people, that recede within a few days.

- Clear communication by healthcare professionals to pregnant women is essential.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Oakes MC, Kernberg AS, Carter EB, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe coronavirus disease 2019 using standardized clinical criteria. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3(3):100319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100319. Epub 2021 Jan 22. PMID: 33493707; PMCID: PMC7826101. | |

Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. for PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. | |

Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. for PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. | |

Allotey J, Fernandez S, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis (Update 2 of the original article published on 1 September 2020). BMJ 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. | |

Smith ER, Oakley E, Grandner GW, et al. Clinical risk factors of adverse outcomes among women with COVID-19 in the pregnancy and postpartum period: A sequential, prospective meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022:S0002-9378(22)00680-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.038. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36027953; PMCID: PMC9398561. | |

Smith ER, Oakley E, Grandner GW, et al. Clinical risk factors of adverse outcomes among women with COVID-19 in the pregnancy and postpartum period: A sequential, prospective meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022:S0002-9378(22)00680-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.038. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36027953; PMCID: PMC9398561. | |

Allotey J, Fernandez S, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis (Update 2 of the original article published on 1 September 2020). BMJ 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. | |

Ellington S, Olson CK. Safety of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis 2022. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00443-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35964615; PMCID: PMC9371585. | |

Kalafat E, Heath P, Prasad S, et al. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(2):136–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.020. Epub 2022 May 11. PMID: 35568189; PMCID: PMC9093065. | |

Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR. Preliminary indings of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2273–82. | |

Prasad S, Kalafat E, Blakeway H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun 2022;132414. | |

Morro PL, Olson CK, Clark E, et al. Post-authorization surveillance of adverse events following COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant persons in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS), December 2020–October 2021. Vaccine 2022 (published online April 12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.031. | |

Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al. Maternal vaccination and risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 among infants. N Engl J Med 2022 (published online June 22). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204399. | |

Prasad S, Kalafat E, Blakeway H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun 2022;132414. | |

Goldshtein I, et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA 2021. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.11035. | |

Wilcox AJ, Rose CE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines preconception and during pregnancy and risk of self-reported spontaneous abortions, CDC v-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry 2020–21, (2021). doi: 10.21203/RS.3.RS-798175/V1. | |

European Medicines Agency; COVID-19 vaccines: key facts; Vaccination during pregnancy. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-key-facts#vaccination-during-pregnancy-section. | |

Kachikis A, Englund JA, Covelli I, et al. Analysis of Vaccine Reactions After COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Doses Among Pregnant and Lactating Individuals. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(9):e2230495. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.30495. PMID: 36074467; PMCID: PMC9459662. | |

Sadarangani M, Soe P, Shulha HP, et al. Canadian Immunization Research Network. Safety of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy: a Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00426-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35964614; PMCID: PMC9371587. | |

Sadarangani M, Soe P, Shulha HP, et al. Canadian Immunization Research Network. Safety of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy: a Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00426-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35964614; PMCID: PMC9371587. | |

Blakeway H, Prasad S, Kalafat E, et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(2):236.e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. Epub 2021 Aug 10. PMID: 34389291; PMCID: PMC8352848. | |

Yang YJ, et al. Association of gestational age at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and a vaccine booster dose with maternal and umbilical cord antibody levels at delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139:373–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004693. | |

Rottenstreich A, et al. Timing of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy and transplacental antibody transfer: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022;28:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.003. | |

Rottenstreich A, Zarbiv G, Oiknine-Djian E, et al. Kinetics of maternally-derived anti- SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in infants in relation to the timing of antenatal vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 2022:ciac480. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac480. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35717644; PMCID: PMC9214162. | |

Prahl M, Golan Y, Cassidy AG, et al. Evaluation of transplacental transfer of mRNA vaccine products and functional antibodies during pregnancy and infancy. Nat Commun 2022;13(1):4422. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32188-1. PMID: 35908075; PMCID: PMC9338928. | |

Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, et al. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15(7):e0234827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234827. PMID: 32645112; PMCID: PMC7347125. | |

Lutz CS, Carr W, Cohn A, et al. Understanding barriers and predictors of maternal immunization: Identifying gaps through an exploratory literature review. Vaccine 2018;36(49):7445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.046. Epub 2018 Oct 28. PMID: 30377064. | |

Regan AK, Kaur R, Nosek M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and coverage among pregnant persons in the United States. Prev Med Rep 2022;29:101977. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101977. Epub 2022 Sep 7. PMID: 36090471; PMCID: PMC9450469. | |

de Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, et al. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020;396(10255):898–908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0. | |

Saitoh A, Takaku M, Saitoh A. High rates of vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022;18(5):2064686. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2064686. Epub 2022 Apr 27. PMID: 35476032. | |

Bhattacharya O, Siddiquea BN, Shetty A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022;12(8):e061477. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061477. PMID: 35981769; PMCID: PMC9393853. | |

Blakeway H, Prasad S, Kalafat E, et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(2):236.e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. Epub 2021 Aug 10. PMID: 34389291; PMCID: PMC8352848. | |

Blakeway H, Prasad S, Kalafat E, et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(2):236.e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. Epub 2021 Aug 10. PMID: 34389291; PMCID: PMC8352848. | |

Miraglia Del Giudice G, Folcarelli L, Napoli A, et al. Collaborative Working Group. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and willingness among pregnant women in Italy. Front Public Health 2022;10:995382. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.995382. PMID: 36262230; PMCID: PMC9575585. | |

Naqvi S, Saleem S, Naqvi F, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy in 7 low- and middle-income countries: An observational trial from the Global Network for Women and Children's Health Research. BJOG 2022. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17226. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35596701; PMCID: PMC9347929. | |

Gunawardhana N, Baecher K, Boutwell A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and perceived risk among pregnant and non-pregnant adults in Cameroon, Africa. PLoS One 2022;17(9):e0274541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274541. PMID: 36099295; PMCID: PMC9469991. | |

Naqvi S, Saleem S, Naqvi F, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy in 7 low- and middle-income countries: An observational trial from the Global Network for Women and Children's Health Research. BJOG 2022. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17226. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35596701; PMCID: PMC9347929. | |

Naqvi S, Saleem S, Naqvi F, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy in 7 low- and middle-income countries: An observational trial from the Global Network for Women and Children's Health Research. BJOG 2022. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17226. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35596701; PMCID: PMC9347929. | |

Hailemariam S, Mekonnen B, Shifera N, et al. Predictors of pregnant women's intention to vaccinate against coronavirus disease 2019: A facility-based cross-sectional study in southwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med 2021;9:20503121211038454. doi: 10.1177/20503121211038454. | |

Gunawardhana N, Baecher K, Boutwell A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and perceived risk among pregnant and non-pregnant adults in Cameroon, Africa. PLoS One 2022;17(9):e0274541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274541. PMID: 36099295; PMCID: PMC9469991. | |

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2022-09-covid-boosters-well-tolerated-pregnancy.html. | |

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)