This chapter should be cited as follows:

Zdanowicz JA, Surbek D, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419083

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 19

Pregnancy shortening: etiology, prediction and prevention

Volume Editors:

Professor Arri Coomarasamy, University of Birmingham, UK

Professor Gian Carlo Di Renzo, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

Professor Eduardo Fonseca, Federal University of Paraiba, Brazil

Chapter

Inducing Miscarriage or Preterm Birth

First published: March 2024

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Induction of labor (IOL) remains a highly relevant part of obstetrics. There are several factors that have to be considered in IOL. The most relevant criteria in induction are indication for IOL (fetal and/or maternal), fetal condition and gestational age at induction. Commonly used indications for IOL according to guidelines are summarized in Table 1.

Post term pregnancy |

Chorioamnionitis |

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

(Preterm) premature rupture of membranes |

Maternal medical complications and conditions |

Fetal compromise or death |

Twin pregnancies |

Psychosocial indications |

While contraindications to IOL are not absolute, these have to be considered carefully. In general, in case of more than one previous cesarean section, IOL is not recommended due to the high risk of uterine rupture. This also includes previous surgeries to the non-pregnant uterus, including certain types of myomectomy, previous uterine rupture, placenta previa as well as vasa previa. Contraindications for IOL are summarized in Table 2.

Vasa previa or placenta previa |

Umbilical cord prolapse |

Previous cesarean section |

Active genital herpes infection |

Previous myomectomy entering the endometrial cavity |

Invasive cervical carcinoma |

Previous uterine rupture |

Transverse fetal position |

Available methods for IOL include pharmacological and mechanical agents. Commonly used pharmacological methods are prostaglandins and their analogs such as dinoprostone and misoprostol (oral, vaginal, sublingual administration) and oxytocin (intravenous administration) in combination with amniotomy. Mechanical methods include balloon catheter, pressure dilatation, osmotic dilatation, extra-amniotic saline infusion and membrane sweeping. Prior to any method used for IOL, adequate and sufficient information has to be provided to the pregnant patient about potential risks as well as benefits, for both mother and fetus and informed consent must be obtained.3,4

Assessment of cervical ripening using the Bishop score should be performed prior to induction, as this is one major factor in choosing the appropriate method for induction and its success rate. The Bishop score includes cervical dilatation, cervical consistency, position of the cervix, fetal head station, and effacement.5 If cervical ripening has not occurred yet, irrespective of gestational age, there is an increased risk in IOL for longer time in labor, higher risk of uterine atony and consequent postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) and potentially increased risk for cesarean section.6

There is a lack of unequivocal definition of what constitutes a failed induction. It has been suggested to use administration of oxytocin for at least 12–18 hours after membrane rupture, without developing contractions or without a change to cervical ripening.7,8

PHARMACOLOGICAL METHODS

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins have hormone-like properties and are known to enhance cervical ripening and induce myometrial contractions. In practice, its synthetic analogs are being used for IOL, namely prostaglandin E2 and E1 analogs. Prostaglandins should be used only after careful assessment in cases of previous cesarean section or for IOL in multiparous women with more than three previous deliveries.9,10 Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 analog and is used via vaginal, sublingual or oral application.

Dinoprostone is a prostaglandin E2. Its most commonly used application forms are cervical gels (usually at 0.5 mg), vaginal gels or ovules (usually 1–3 mg) and vaginal inserts (10 mg), while suppositories are used less frequently. Vaginal inserts should not be left for more than 24 hours intravaginally, while cervical gels, vaginal gels or ovules can be re-applied after 6 hours if necessary.

The use of prostaglandins for IOL at term seems effective, however, there are no consistent data on dose regimen as well as on fetal and maternal morbidity and use in preterm IOL.11

Sulprostone

Sulprostone is an oxytocin-agonist and a prostaglandin E2 analog. As it causes the uterine arteries to contract, potentially leading to placental abruption, it is contraindicated to use in live birth.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a hormone that both stimulates uterine contractions directly and induces prostaglandin production to further enhance myometrial contractility. It is most effective in combination with amniotomy to enhance its effect on the uterus and promote contractions. In general, oxytocin is applied intravenously and continuously in titrating dosage to decrease the risk of uterine hyperstimulation. Low- and high-dose regimen have been described for IOL and both seem to be equally effective and safe.1,2,12 In a low-dose regimen, the starting dose of oxytocin is 0.5–2 mU/min, with incremental increase of 1–2 mU/min every 15–40 minutes. In a high-dose regimen, the starting dose is 6 mU/min, with an incremental increase of 3–6 mU/min every 15–40 minutes.13,14 In general, a Bishop score of at least 5 is considered favorable for IOL with oxytocin.2

MECHANICAL METHODS

Balloon catheter

The most commonly used catheters are Foley or double-balloon catheters (e.g., Cook® Double-Balloon Catheter). They provide a more gentle method for IOL, which is preferred for unripe Bishop scores, particularly after previous cesarean section. The advantages of balloon catheters are lower risk of uterine hyperstimulation and uterine rupture compared to prostaglandins. However, on the other hand, it is less effective than prostaglandins in terms of interval between induction and delivery.1,2,15

Osmotic dilatation

Here, so-called laminaria sticks are used to mechanically enhance cervical dilatation. They are inserted into the cervical canal and inflate in size by absorbing surrounding fluids, causing the cervical canal to dilate. They have been shown to be just as effective as prostaglandins for IOL with fewer side-effects.16,17

Membrane sweeping

This is not a medical method for IOL but can serve as preparation of the cervix. It is performed by inserting a gloved finger into the cervix. A mechanical detachment of the amniotic sac is achieved by gentle sweeping the cervix with the finger and, consequently, endogenous hormones are released to enhance cervical ripening and IOL. It is usually performed in term pregnancies after 39 weeks of gestation. Undesirable effects include bleeding/spotting and maternal discomfort during or after the procedure.

A comparison of different methods for IOL can be found in Table 3.

3

Summary of different induction methods and its effect on mode of delivery and perinatal outcome.14

Induction regimen | Comparison group | Vaginal delivery rate | Cesarean delivery rate | Perinatal outcomes |

Oxytocin | Placebo Prostaglandins | Increased Reduced | – Increased | – – |

Prostaglandins | PGE1 vs PGE2 Oral PGE1 vs vaginal PGE1 Oxytocin | Increased Likely increased Increased | No change No change Likely reduced | – No change in uterine hyperstimulation – |

Mechanical dilation | Prostaglandins Oxytocin | Likely no change Likely no change | No change Reduced | Reduced risk of uterine hyperstimulation – |

Amniotomy combined | Early vs late PGE1 and Foley catheter vs single agent Oxytocin and Foley catheter vs single agents PGE1 and Foley catheter vs oxytocin and Foley catheter | Likely no change Likely increased Likely increased Likely increased | Likely no change No change No change No change | No change in chorioamnionitis Possible increased risk of chorioamnionitis No change No change in chorioamnionitis |

In the following sections, IOL for miscarriage and stillbirth as well as preterm delivery will be discussed in more detail.

INDUCTION OF LABOR IN MISCARRIAGE

The definition of miscarriage and stillbirth vary and are sometimes used interchangeably. In the USA, miscarriage is defined as a pregnancy loss below 20 weeks of gestation, while a stillbirth is any fetal loss above 20 weeks of gestation or fetal weight of at least 350 g.18,19 Other guidelines define stillbirth as pregnancy loss after 24 weeks (UK) or 28 weeks (WHO) of gestation and any pregnancy loss prior to that as miscarriage.20 In the following text passage, the term stillbirth will be used for any pregnancy loss after 14 weeks’ gestation.

The incidence of stillbirth in the US is 1 in 160 deliveries with 26,000 stillbirth deliveries per year.19,21,22 Worldwide, 2% of deliveries are stillbirth with 3.2 million cases per year starting at 28 weeks.23 Risk factors for stillbirth include obesity, chronic hypertension, pregestational and gestational diabetes, use of artificial reproductive technologies, multiple gestation, younger and older maternal age, male sex of fetus, fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.24 Counseling for subsequent pregnancies, bereavement and prenatal as well as postnatal assessment of causes should be performed and are an important part in the management of stillbirth, but are not the topic of this chapter. A review of recommended stillbirth investigations can be found here.24

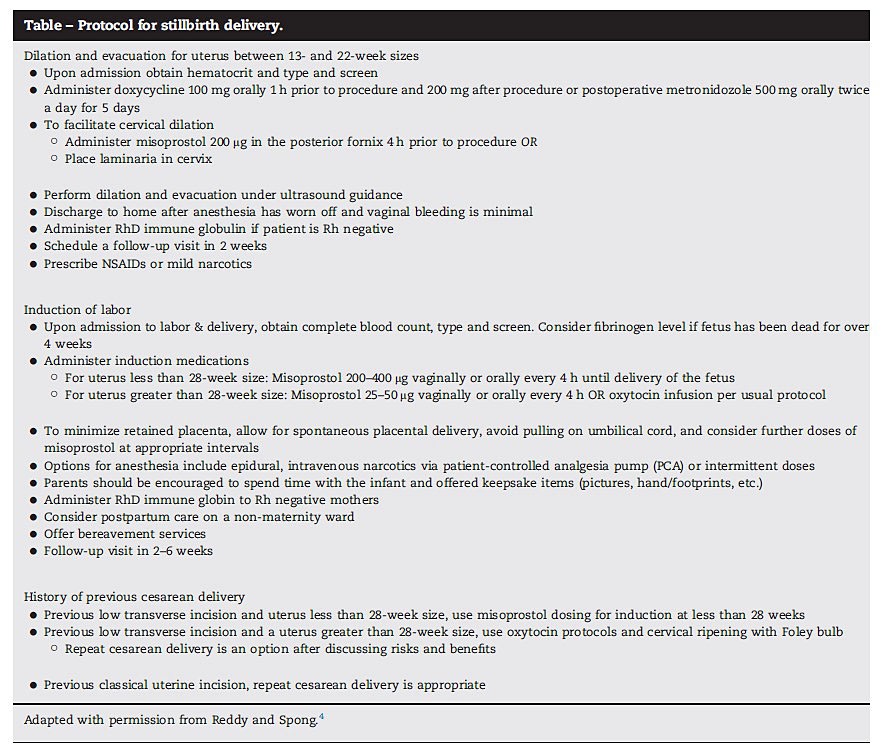

IOL between 14 and 24 weeks may require a subsequent dilatation and curettage for removal of placenta (remnants) with a higher risk for maternal morbidity.19,25 Therefore, some guidelines, specifically in the USA, recommend a dilatation and curettage instead of IOL between 14 and 24 weeks, which also bears a lower risk for maternal infection.25,26 In these cases, fetal size appears to be more relevant than actual gestational age. This surgical procedure carries inherent risks and must be performed by gynecologists experienced with the procedure.

In stillbirth, vaginal delivery after IOL if necessary is preferred, unless there are contraindications, as described in Table 2.19 In 80–90% of cases, spontaneous labor will develop within 2–3 weeks of stillbirth,21,24 nevertheless, IOL yields more favorable results to terminate the pregnancy. Affected women should, however, not be rushed into IOL unless an immediate risk to the mother’s health exists. Furthermore, the risk for infection or coagulopathy within 48 hours appears to be low except in cases with PROM or placental abruption.24,27 While fetal monitoring during delivery is obsolete for obvious reasons in these cases, there should still be an assessment of fetal and placental position, and intermittent surveillance of the pregnant woman during the procedure.

Factors associated with cesarean section in stillbirth seem to be similar as in live pregnancies.18,22 However, the indication to perform a cesarean section instead of choosing a vaginal delivery do not seem to be clear and the cesarean section rate in stillbirth is around 15%, while the psychological benefit of cesarean section in stillbirth remains unclear.18,22

Practical approach

Prior to induction when the cervix is unripe, cervical priming and preparation of the uterus can be carried out using mifepristone, a progesterone receptor modulator that increases uterine sensitivity to prostaglandins. It appears to be most effective at a dose of 200 mg when administered orally 24–48 hours before induction.28 In cases where contractions have already started or cervical ripening is advanced, cervical priming might be obsolete.

In general, IOL for stillbirth has been most commonly described using misoprostol and oxytocin. A low-dose regimen of misoprostol can be applied in stillbirth after 28 weeks, using 25 or 50 μg every 3–6 hours by vaginal route (for a max of 200 μg in 24 hours).29 In stillbirth at 14–28 weeks of gestation, misoprostol can be used at higher doses (400–600 μg vaginally every 3–6 hours with up to five doses in 24 hours).30 As mentioned above, misoprostol should probably not be used in cases of previous cesarean section, due to an elevated risk for uterine rupture as compared with other prostaglandins. In the critical period between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, IOL seems to be effective when using misoprostol combined with prior application of mifepristone.31 For 28–37 weeks of gestation, misoprostol can be used according to standard IOL protocols. Vaginal application for IOL is more effective for delivery within 24 hours with fewer side-effects than oral application.30,32 However, some studies have shown that oral application of misoprostol has a lower rate of uterine hyperstimulation that vaginal application or dinoprostone;33,34,35 therefore, it is recommended in term pregnancy with a viable fetus.

Oxytocin for IOL in stillbirth can be used in standard dosage used for IOL as described above.

While the use of intravenous sulprostone for IOL is contraindicated when the fetus is alive, it can be used in stillbirth after failure of oxytocin or prostaglandins for IOL. However, due to an increased risk for uterine rupture, a restricted use is recommended. Regarding mechanical methods and its use in miscarriage/stillbirth, the same indications and contraindication appear to apply as in standard obstetric IOL protocols.

In stillbirth, not one IOL method appears to be more effective, but overall, there is a high success rate for IOL.18 Recommendations for IOL of stillbirth across guidelines vary, with some obstetrics societies recommending a standard IOL protocol using misoprostol and oxytocin (ACOG), mifepristone combined with prostaglandins (NICE) or misoprostol only (WHO).1 A possible detailed protocol for stillbirth management starting at 14 weeks of gestation with dilatation and curettage has been described in detail and is shown in Figure 1.21

1

Protocol for stillbirth delivery, starting at 14 weeks of gestation. Reproduced with permission from Chakhtoura and Reddy, 2015.21

INDUCTION OF LABOR IN PRETERM BIRTH

While IOL and available induction methods have been widely studied, specific guidelines for preterm IOL have not been established. Once the limit of viability has been reached at 24 weeks of gestation as defined by most guidelines, the indication for IOL must be considered and evaluated carefully. Prior to 32 weeks of gestation, the indication for IOL instead of opting for a cesarean delivery may be preferable in selected cases. Vaginal delivery is recommend after 28–30 weeks in absence of contraindications in most guidelines. Fetal position and placenta localization should be verified before beginning IOL. Furthermore, regular fetal monitoring using cardiotocography (CTG) before onset of regular contractions is recommended.

Possible and most frequent indications include premature preterm rupture of membranes (PPROM), multiple pregnancies, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), including pre-eclampsia and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets), fetal growth restriction (FGR), fetal macrosomia, gestational diabetes and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. In some cases, women might also opt for an elective preterm induction of labor, even if from a purely medical point of view, the pregnancy could be continued to term. In these cases, there has to be careful evaluation and informed consent has to be documented. Generally, benefits of IOL have to outweigh the risk for neonatal complications of preterm birth, as well as preventing stillbirth. One of the most common iatrogenic IOL indications are PPROM and multiple gestations and are therefore discussed in more detail.

PPROM

PPROM are defined as a rupture of membranes before completed 37 weeks of gestation. By most guidelines, an expectant management in case of PPROM is justifiable until completed 34 weeks of gestation. However, in case of complications, earlier delivery is recommended and should be evaluated carefully. Possible indications and complications included infection, placental abruption or repeated vaginal bleeding, umbilical cord prolapse or signs of fetal stress as documented by CTG. In cases of PPROM, induction of labor is recommended at 32 weeks (SOGC) and at 34 weeks (NICE, ACOG) of gestation.1,36 Regarding IOL after PPROM between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation, benefits versus potential risks (infection, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse) of expectant management after 34 weeks have to be evaluated and discussed with the patient.

Multiple gestation

Twin pregnancies pose a special situation in IOL of preterm birth. Generally, as the risk for stillbirth increases with advancing gestational age, guidelines recommend iatrogenic preterm birth. In favorable conditions, IOL can be recommended, however, patients should be adequately counseled on peripartal risks. According to international guidelines, monochorionic monoamniotic (MCMA) twins should be delivered between 32 and 34 weeks of gestation and monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) twins between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation, while dichorionic diamniotic (DCDA) twins can be delivered at term,37 as summarized in Table 4. In case of twin complications such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), selective FGR or twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS), the optimum timing of delivery and hence possibly IOL depends on the severity of the complications as well as gestational age. Regarding IOL of higher order pregnancies no recommendations can be made due to lack of sufficient data.

Society | DCDA twins | MCDA twins | MCMA twins |

NICE, UK | 37 0/7–37 6/7 | 36 0/7–36 6/7 | 32 0/7–33 6/7 |

RCOG, UK | – | From 36 0/7 | 32 0/7–34 6/7 |

ACOG, USA | 38 | 34 0/7–37 6/7 | 32–34 |

RANZCOG, Australia and New Zealand | – | Up to 37 | – |

CNGOF, France | 38–<40 | 36–<38 6/7 | 32–<36 |

DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic.

While delivery mode for MCMA twins should always be cesarean section, for MCDA and DCDA twins, recommendations on uncomplicated pregnancies are depicted in Table 5 across various international guidelines. There are no contraindications on using the same methods for IOL as in singleton pregnancies. Furthermore, in twin pregnancies, not one method appears to be superior to other methods used.39,40

5

Recommendations on delivery mode in uncomplicated twin pregnancies.37

Society | DCDA twins | MCDA twins | MCMA twins |

NICE, UK | Vaginal delivery possible if

| Vaginal delivery possible if

| Cesarean section |

RCOG, UK | – | Vaginal delivery | Cesarean section |

ACOG, USA | Vaginal delivery >32 weeks irrespective of presentation second twin | Vaginal delivery >32 weeks irrespective of presentation second twin | Cesarean section |

RANZCOG, Australia and New Zealand | Vaginal delivery if continuous fetal monitoring or emergency cesarean section can be provided | Vaginal delivery if continuous fetal monitoring or emergency cesarean section can be provided | – |

CNGOF, France | Vaginal delivery irrespective of gestational age and presentation of twins | Vaginal birth regardless of gestational age and child presentation | – |

DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic.

Practical approach

Administration of prostaglandins should follow a clearly defined clinical protocol. For misoprostol, vaginal application of 25–50 μg every 4–6 hours, with a maximum dose of 200 μg in 24 hours is recommended. The recommended dose for oral misoprostol is 25–50 μg every 2–4 hours. If oxytocin is used for further stimulation, there should be a break of at least 4 hours after the last application of misoprostol before starting with oxytocin.1,2,41 If dinoprostone is used, the recommended dosage is as described above. For IOL with oxytocin, the use of a low- and high-dose regimen can be used as described above. Amniotomy should not be used as a first-line method of IOL, however, it appears to be an effective method in combination with oxytocin in a favorable cervix.1 The use of mechanical methods such as balloon catheter or osmotic dilatator in preterm birth appears to be safe. Membrane sweeping is not explicitly recommended.

Overall, data specifically on preterm induction of labor is scarce. A recent overview of international guidelines, including the UK, USA, Canada and WHO, calls for a standardization of IOL management.1

CONCLUSION

Data specifically for IOL in miscarriage after 14 weeks and particularly preterm birth are scarce. Furthermore, existing national and international guidelines regarding IOL vary and are not consistent. In the absence of contraindications, prostaglandins and oxytocin appear to be a safe option, while data on using mechanical methods in preterm IOL also appear to be insufficient. However, from what few data are available specifically in preterm delivery, no methods for IOL appears to be superior to another in the absence of contraindications. Careful individual evaluation and a patient-oriented approach with informed consent should be the baseline at the beginning of each IOL, with maternal and fetal safety in case of preterm delivery remaining the highest priority.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Prior to induction of labor (IOL) , there has to be sufficient and adequate informed consent of the patient about potential risks as well as benefits, for both mother and fetus.

- Indication and contraindications for IOL should be carefully evaluated.

- Currently, there are no uniform IOL guidelines for either stillbirth or preterm delivery.

- In case of miscarriage/stillbirth between 14 and 24 weeks of gestation, medical IOL is standard of care in many countries, while dilatation and curettage can be considered, based on fetal size rather than gestational age, if performed by an experienced gynecologist-obstetrician.

- After 28–30 weeks of gestation, vaginal delivery is preferred to cesarean section for preterm birth for most indications. In stillbirth, IOL is standard of care, and cesarean section should only be performed in rare cases.

- Pharmacological and mechanical methods are available for IOL, and the selected method should be based on an individual evaluation of possible risks and contraindications.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J Zdanowicz – Consultant and lecture fees: CSL Vifor and NovoNordisk, in favor of departmental research fund.

Daniel Surbek – Advisory board and lectures Ferring and Norgine, in favor of departmental research fund.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Tsakiridis I, Mamopoulos A, Athanasiadis A, et al. Induction of Labor: An Overview of Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2020;75(1):61–72. | |

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(2 Pt 1):386–97. | |

Coates R. Attitudes of pregnant women and healthcare professionals to labour induction and obtaining consent for labour induction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2021;77:64–75. | |

Coates D, Goodfellow A, Sinclair L. Induction of labour: Experiences of care and decision-making of women and clinicians. Women Birth 2020;33(1):e1–14. | |

Bishop EH. Pelvic Scoring for Elective Induction. Obstet Gynecol 1964;24:266–8. | |

Bacak SJ, Olson-Chen C, Pressman E. Timing of induction of labor. Semin Perinatol 2015;39(6):450–8. | |

Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, et al. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210(3):179–93. | |

Becker DA, Szychowski JM, Kuper SG, et al. Labor Curve Analysis of Medically Indicated Early Preterm Induction of Labor. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134(4):759–64. | |

ACOG Practice bulletin No. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(2 Pt 1):450–63. | |

Hoffman MK, Hunter Grant G. Induction of labor in women with a prior cesarean delivery. Semin Perinatol 2015;39(6):471–4. | |

Thomas J, Fairclough A, Kavanagh J, et al. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014(6):Cd003101. | |

Smith JG, Merrill DC. Oxytocin for induction of labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2006;49(3):594–608. | |

Ramirez MM. Labor induction: a review of current methods. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2011;38(2):215–25, ix. | |

Saucedo AM, Cahill AG. Evidence-Based Approaches to Labor Induction. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2023;78(3):171–83. | |

de Vaan MD, Ten Eikelder ML, Jozwiak M, et al. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023;3(3):Cd001233. | |

Gavara R, Saad AF, Wapner RJ, et al. Cervical Ripening Efficacy of Synthetic Osmotic Cervical Dilator Compared With Oral Misoprostol at Term: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139(6):1083–91. | |

Gupta JK, Maher A, Stubbs C, et al. A randomized trial of synthetic osmotic cervical dilator for induction of labor vs. dinoprostone vaginal insert. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022;4(4):100628. | |

Boyle A, Preslar JP, Hogue CJ, et al. Route of Delivery in Women With Stillbirth: Results From the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(4):693–8. | |

Management of Stillbirth: Obstetric Care Consensus No. 10. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135(3):e110-e32. | |

Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, et al. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10(Suppl 1):S1. | |

Chakhtoura NA, Reddy UM. Management of stillbirth delivery. Semin Perinatol 2015;39(6):501–4. | |

Rossi RM, Hall ES, DeFranco EA. Mode of delivery in antepartum stillbirths. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2019;1(2):156–64.e2. | |

Stanton C, Lawn JE, Rahman H, et al. Stillbirth rates: delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet 2006;367(9521):1487–94. | |

Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Mamopoulos A, et al. Investigation and management of stillbirth: a descriptive review of major guidelines. J Perinat Med 2022;50(6):796–813. | |

Bryant AG, Grimes DA, Garrett JM, et al. Second-trimester abortion for fetal anomalies or fetal death: labor induction compared with dilation and evacuation. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(4):788–92. | |

Edlow AG, Hou MY, Maurer R, et al. Uterine evacuation for second-trimester fetal death and maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(2 Pt 1):307–16. | |

Silver RM. Fetal death. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109(1):153–67. | |

Chaudhuri P, Datta S. Mifepristone and misoprostol compared with misoprostol alone for induction of labor in intrauterine fetal death: A randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41(12):1884–90. | |

Gómez Ponce de León R, Wing D, Fiala C. Misoprostol for intrauterine fetal death. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007;99(Suppl 2):S190–3. | |

Gómez Ponce de León R, Wing DA. Misoprostol for termination of pregnancy with intrauterine fetal demise in the second and third trimester of pregnancy – a systematic review. Contraception 2009;79(4):259–71. | |

Perritt JB, Burke A, Edelman AB. Interruption of nonviable pregnancies of 24–28 weeks' gestation using medical methods: release date June 2013 SFP guideline #20133. Contraception 2013;88(3):341–9. | |

Dodd JM, Crowther CA. Misoprostol for induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second or third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or after intrauterine fetal death. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;2010(4):Cd004901. | |

Alfirevic Z, Aflaifel N, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014(6):Cd001338. | |

Kerr RS, Kumar N, Williams MJ, et al. Low-dose oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;6(6):Cd014484. | |

Muzonzini G, Hofmeyr GJ. Buccal or sublingual misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;2004(4):Cd004221. | |

Tsakiridis I, Mamopoulos A, Chalkia-Prapa EM, et al. Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes: A Review of 3 National Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2018;73(6):368–75. | |

von Kaisenberg C, Klaritsch P, Ochsenbein-Kölble N, et al. Screening, Management and Delivery in Twin Pregnancy. Ultraschall Med 2021;42(4):367–78. | |

Good clinical practice advice: Management of twin pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;144(3):330–7. | |

Mei-Dan E, Asztalos EV, Willan AR, et al. The effect of induction method in twin pregnancies: a secondary analysis for the twin birth study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17(1):9. | |

Jonsson M. Induction of twin pregnancy and the risk of caesarean delivery: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:136. | |

Leduc D, Biringer A, Lee L, et al. Induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35(9):840–57. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)