This chapter should be cited as follows:

Berger-Chen SW, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418323

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 2

Adolescent gynecology

Volume Editor: Professor Judith Simms-Cendan, University of Miami, USA

Chapter

Reproductive Tract Anomalies – An Overview

First published: June 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Mullerian anomalies are estimated to occur at a rate of approximately 5–7% in the general population.1 The diversity in which they can present over a lifetime makes understanding of these conditions important for all providers caring for reproductive-aged women. The scope of this document is to review the current classification of reproductive anomalies, their common presentations, and the recommendations for diagnosis and management.

Reproductive anomalies can have significant long-term impacts on patients’ lives, their body image, and their reproductive ability. Primary management, when possible, should be conducted by a provider or team that is familiar in the management of complex anomalies. Understanding the embryologic development of the Mullerian tract and urogenital sinus can help clarify the orientation of anatomical structures in patients presenting with developmental anomalies and guide diagnosis and management.

EMBRYOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

Development of the Reproductive Tract

Differentiation of the female urogenital tract begins in the early stages of the gestational period around 6 weeks. Over the subsequent 15 weeks complex differentiation occurs and is triggered by a cascade of cell signaling and transcription factors that is not fully understood. Both genetic and environmental factors likely play a role in the disruption of the systems development.2

Disruption in the formation of the Mullerian tract is likely multifactorial: genetic variation with differing penetrance, maternal sex steroid levels, and environmental factors such as endocrine disruptors can all play a role. The most well-known iatrogenic cause of Mullerian anomalies was the medication diethylstilbestrol, which was used to prevent miscarriage over a period of 20–25 years in the US starting in the 1950s3 and was associated with a T-shaped uterus, incompetent cervix, vaginal adenosis, and cancer.

Usual Development

The Mullerian ducts differentiate from the Wolffian or Mesonephric ducts early in development in the fifth–sixth week. Differentiation is triggered by the presence or absence of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. The Mullerian ducts arise along the surface of the paired urogenital ridges. The Mullerian ducts continue to extend caudally towards the urogenital sinus to form the Mullerian tubercle and generally occurs by the seventh–eighth week of gestation. Failure in any part of these early stages of development results in the combined anomalies involving the renal and reproductive tracts; uterovaginal agenesis, cervical agenesis, and vaginal agenesis.

After the communication with the urogenital sinus the lateral Mullerian ducts fuse in the midline. The septum from the two ducts joining begins to regress around the ninth week of gestation. With the regression of the septum the uterovaginal canal will be formed. A failure in this stage of development or canalization results in the uterovaginal anomalies associated with utero-vaginal septa as well as uterine corpus anomalies; bicornuate uteri, unicornuate uterus, uterine didelphys, and arcuate uterus.

Signaling for this system is still not fully understood. A mutation or knockout of the gene loci LHX1 results in a failure of the myometrium to form and is associated with uterovaginal agenesis.2 The cellular differentiation and completed organogenesis will continue until approximately 21 weeks of gestation.

Uterine anomalies, excluding agenesis, are the result of either the failure of the Mullerian ducts to fuse in the midline or failure of canalization after the fusion of the Mullerian ducts. With near complete canalization the uterus may be designated as arcuate or heart shaped. An arcuate uterus is considered a normal variant and does not have any significant impact on fertility or obstetric outcome.4 The uterine anomalies associated with failure of complete canalization or fusion include unicornuate uterus, bicornuate uterus, and uterine didelphys.

1

Malformations based upon abnormal Mullerian duct development.2

Fusion Abnormalities | Regression Abnormalities | Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Exposure |

|

|

|

Complete absence of the uterus and upper vagina – failure of Mullerian duct development or failure of Wolffian duct development.

Inheritance and Genetics

Several anomalies have been associated with genetic syndromes. Examples include McKusick-Kaufman and Bardet-Biedl, two autosomal recessive syndromes are associated with vaginal atresia. Vaginal atresia occurs in the general population at rates of 1/4,000–1/10,000. Decherney syndrome is associated with transverse vaginal septa and bladder extrophy as well as a displaced bicornuate uterus. A mutation in the HOXA13 gene resulting in a hand–foot–genital syndrome is known to result in a longitudinal vaginal septum.5

External genital anomalies include the imperforate hymen, which occurs with an incidence of 1/1,000 and is one of the most encountered anomalies of the reproductive tract. An increased incidence in siblings suggest an autosomal recessive inheritance and underscores the importance of a family history at presentation. Cases of monozygotic twins with imperforate hymen suggest an alternate autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Mutations and variants in HOXA10, HOXA11, PAX2, PBX1, WNT7A, and LHX1 have all been reported in cases of reproductive tract anomalies such as uterine didelphys. No single gene is associated with a single anomaly at this time.5

Interestingly, Mullerian aplasia, known more commonly as Mayer Rokitansky Kuster Hauser syndrome (MRKH) presents in isolation as type 1 Mullerian aplasia or in a complex of anomalies known as type 2 Mullerian aplasia. A complex type 2 syndrome is known as MURC’s syndrome (Mullerian duct aplasia, renal agenesis, cervicothoracic somite dysplasia) B.5 This underscores the complex nature of the differentiation and signaling that occurs in the development of the mesonephric and Mullerian systems.

Classification

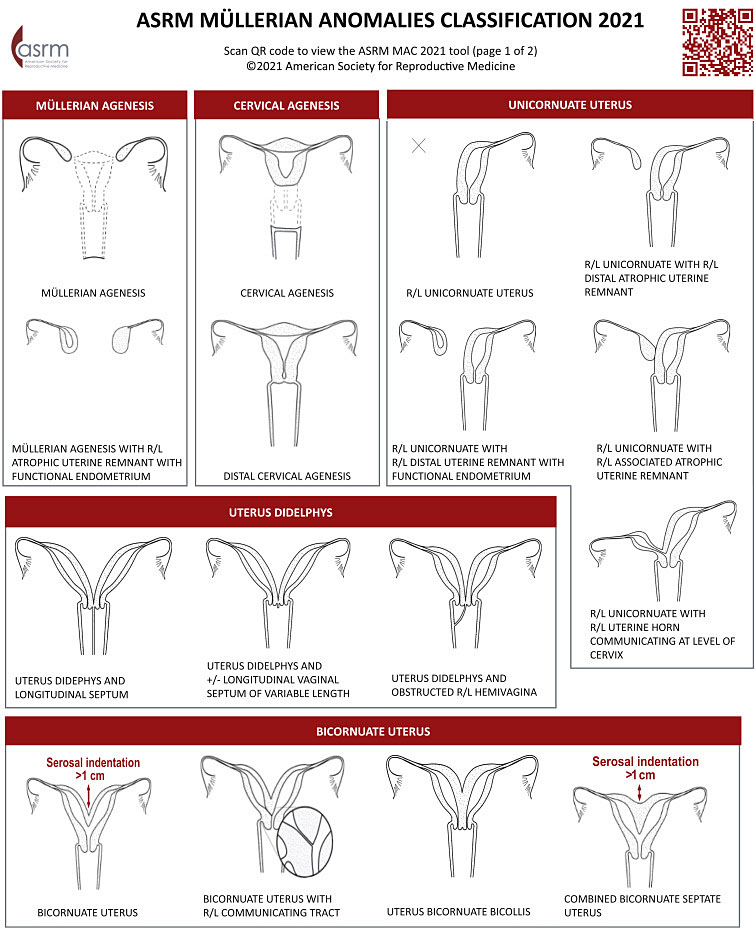

The reproductive anomalies included in this chapter will include both lower and upper genital anomalies. The lower genital tract includes the hymen and vagina. The upper genital tract includes the cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Anomalies associated with the upper tract include ovarian mal-descent, absence of the fallopian tube, cervical aplasia, and uterine anomalies. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine Mullerian Anomalies Classification 2021 (MAC 2021)6 will be referenced when applicable for genital tract anomalies.

The MAC 2021 classifies Mullerian anomalies into nine categories based on similar elements in appearance, presentation, and treatment. This classification system will be followed as the primary classification system in this chapter. Mullerian anomalies represent a continuum of development, and many have combined elements, some anomalies may appear in more than one category.

1

ASRM Müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Courtesy of ASRM.6

Reproductive Tract Anomalies: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management

Presentation

Presentation can often be divided in patients who present with menstrual or functional abnormalities, which are generally associated with nonobstructive anomalies. Nonobstructive anomalies present in a diverse fashion over a range of ages. The range of symptomatology could be from irregular menses, recurrent miscarriage to dyspareunia. This is in comparison to patients who present with signs and symptoms of an obstructive anomaly. Obstructive anomalies present in the later pubertal stages when menarche is expected. These anomalies generally present acutely with primary amenorrhea, which may also be associated with abdominal-pelvic pain or mass.

In early life, a newborn with imperforate hymen may present with a mucocolpos that can be symptomatic causing urinary or gastrointestinal obstruction. If the mucocolpos is large enough it can even contribute to diaphragmatic pressure leading to respiratory distress.7,8

In adolescence, obstructive Mullerian anomalies present as primary amenorrhea, cyclic pain or acute pain or urinary retention due to a large hematocolpos.8 Often these patients are first encountered in acute distress, in severe pain and with a mass on imaging. It is at this juncture that the most critical interventions will be made. First and foremost it is absolutely not necessary to proceed with an immediate surgical intervention. If there is any uncertainty about the anatomy or diagnosis, and if the provider does not have experience in managing these types of cases of complex reproductive anomalies surgery should be deferred. Pain management and menstrual suppression in addition to continuous or intermittent bladder catheterization and stool softener can often be excellent initial interventions. Menstrual suppression can be managed with continuous oral contraceptives, progestin only methods, or GnRH agonist-antagonist medications with add back therapy. Cyclic pain and endometriosis can be associated with both partially obstructed anomalies as well as obstructive anomalies.

In addition to primary management with a team familiar with these types of anomalies a second urgent tenet of management is the avoidance of ANY FORM of transvaginal drainage through an obstruction. This can lead to ascending infection and long-term sequalae, which can impact a patient’s future fertility or even result in sepsis.9 Finally, deferred interventions to expert management can avoid complications such as incomplete resection of a transverse vaginal septum, which can lead to stenosis and reaccumulation of the hematometra or hematocolpos. Furthermore, it is well documented that prolonged retrograde menstruation including reaccumulation of hematometra is a significant risk factor for the development of endometriosis and its sequalae.10

Renal Anomalies

When considering presentation concomitant conditions such as renal anomalies should raise a provider’s index of suspicion. An estimated total prevalence in patients with renal anomalies was found to be approximately 29%.11 Prevalence is higher still in patients with renal agenesis found to be 32% and with renal dysgenesis 25%.11 The most common Mullerian anomaly associated with renal anomalies is failure of Mullerian duct fusion.11 This condition specifically can be further associated with renal and skeletal abnormalities.

LOWER GENITAL TRACT – HYMEN AND VAGINA

Hymeneal Abnormalities – Complete and Incomplete

Anatomy

Hymeneal abnormalities result from a failure of the canalization of the sino-vaginal bulb.

Epidemiology

Imperforate hymen occurs at an incidence of approximately 1/1,000 and is the most encountered reproductive tract anomaly. It can be familial.

Presentation

Hymeneal abnormalities are variable in their presentation. The abnormalities can sometimes be found during a routine exam with the abnormality visible at the introitus. In younger patients this can be done with gentle downward and lateral traction of the labia majora.12 In the case of a microperforate hymen a patient may complain of prolonged menstrual bleeding or discharge as their vault is not completely evacuating the menstrual blood. Imperforate hymen can often be diagnosed on examination at the time of presentation. With gentle labia majora traction in the downward and lateral direction, often even this is not necessary as the vaginal bulge is obvious on examination. The hymen is a thin, membranous tissue and with blood behind it will often adopt a bluish hue. Furthermore, with Valsalva a patient can distend it further helping to confirm the diagnosis. If there is any question or concern about an imperforate hymen an MRI, which includes visualization of the perineum will often reveal a thin membrane. If the tissue is greater than 1 cm in thickness, there is concern for a transverse vaginal septum and expert opinion may be warranted to avoid surgical complications. In microperforate or septate hymens, upper genital tract imaging is not necessary in the case of hymeneal variants as they are not associated with other anomalies with significant frequency.

Diagnosis and Management

Management of an imperforate hymen is generally done under general anesthesia. The membrane can be opened through a cruciate incision with each wedge resected in turn. Alternately crescentic incision can be made, and the tissue excised. Bipolar cautery is sufficient for the resection of the tissue. The hymeneal rim can be oversewn with absorbable suture. Finally, recall that the vaginal canal has been distended and can be thin and friable instrumentation of the vaginal canal with suction or speculum should be done with this in mind. Furthermore, the cervix may be dilated secondar to hematometra adding a risk for ascending infection. A gentle irrigation with sterile saline solution may be performed but is often not necessary as the blood will drain with the incision and postoperatively as the uterus involutes. (ACOG Hymeneal variants). Microperforate hymen would require management like that of an imperforate hymen with a cruciate or excisional procedure done in the operating room.

A septate hymen can sometimes be managed in the office with topical anesthesia depending on the width of vaginal attachments and patient maturity and comfort. First, a topical anesthetic is applied liberally to the introitus. Next the anterior and posterior attachments are clamped with small hemostats, and suture ligated with the clamp left in place to allow for tissue necrosis. The clamps can then be removed, and the septum resected just below the ties at the superior and inferior pedicles.12

Vaginal Septa

Anatomy

|

|

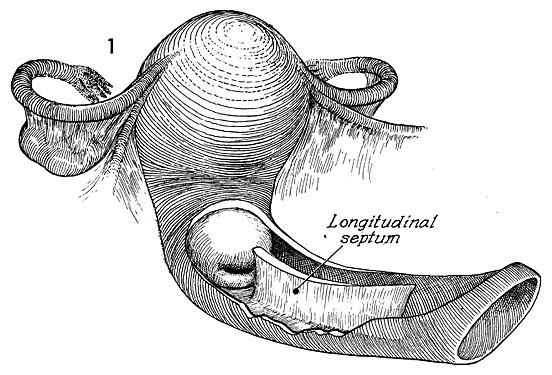

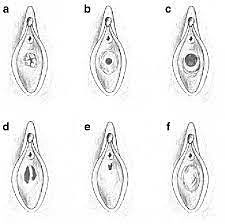

3

Longitudinal and transverse vaginal septum. Reproduced with permission from Clifford et al.15

Presentation

Vaginal septa have variable presentation dependent on whether they are complete or partial and symptoms, which may be associated with concurrent anomalies.

Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

Anatomy

A longitudinal septum divides the vaginal canal in the cranial-caudal plane. The canals are not always equal in size. It is a result of incomplete Mullerian fusion and can be partial or complete. It is associated with a normal uterine cavity in addition to a septate or hemiuterus. Hemituteri can be single or double and separation in a double uterus can be complete to partial. There can be variable connection between two hemiuteri. Cervices can also be duplicated or single.6

Management

A longitudinal septum should be resected as a traumatic avulsion with intercourse or vaginal delivery can result in hemorrhage and vaginal trauma. It is also frequently obscuring a second cervix. This second cervix needs to be screened for cervical cancer and requires visual access to complete the pap smear. When counseling for future fertility the presence of a longitudinal septum may be associated with uterine anomalies that could place a patient at risk for pregnancy related complications.

Diagnosis

Imaging in the form of a 3D ultrasound or MRI is warranted, although noted to be equally effective in the diagnosis of upper genital tract anomalies.16 Associated uterine malformation in the case of a longitudinal vaginal septum are present in 87.4% of patients. This is true especially in partial high septa.17 The differential diagnosis includes incomplete transverse septum, hymeneal abnormalities, vaginal adhesions, and vaginismus.6 For further evaluation and clarification of the vaginal anatomy an MRI with aqueous vaginal gel in the nonobstructed portion of the vagina can clarify the length and diameter of the septum.6

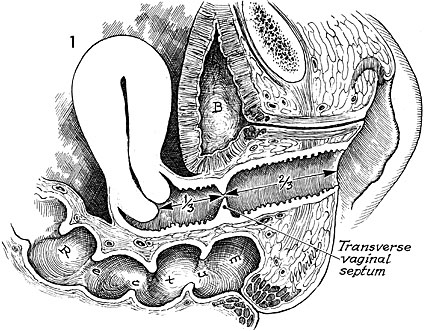

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Epidemiology

Transverse vaginal septa occur in 1/21,000–1/84,000 people. They are unlikely to be associated with other anomalies. However, there have been case reports, which concurrent renal anomalies.

Presentation

Most patients will present with a complete transverse vaginal septum.18 This condition can often be differentiated from imperforate hymen as it rarely has a perineal bulge due to the thick tissue present with this condition. Cervical agenesis and partial Mullerian agenesis with functional endometrium can also present with a similar clinical picture.6 It generally presents with a hematometra and a degree of hematocolpos depending on the level of obstruction. The septum can occur at any portion of the vagina but is most commonly found in a high or mid location when the vagina is roughly divided in thirds.

Diagnosis

An initial diagnosis via ultrasound can be made although sometimes it can be difficult to differentiate between cervicovaginal atresia and cervical atresia. In this diagnosis an MRI is an excellent diagnostic adjunct as it can look at the soft tissue present at the level of obstruction. Furthermore, it can measure the thickness and location of the septum, which is essential in surgical planning. After initial diagnosis urgent surgical intervention is not necessary. MRI T2-weighted sagittal images best delineate the relationship between endometrial cavity and inferior structures of cervix and apex of the vagina. MRI T2-weighted axial images best assess the presence of fibrous septa in relation to vaginal and uterine tissue.6

Management

A carefully planned surgical intervention is essential to a functional outcome and prevention of stenosis. Urgent surgical management upon presentation is NOT necessary. Timing of surgical intervention is critical to a successful outcome as dilation postoperatively is imperative in preventing stenosis and adhesion formation. Menstrual suppression until a patient is ready for postoperative dilator care is an important option. Dilation against the septum preoperatively can also thin the tissue facilitating resection. Accumulation of hematocolpos preoperatively can also autodilate the canal and allow for orientation during the septum resection by confirming the entry of the upper vagina during the resection.

When the septum is clearly delineated and less than a centimeter in thickness a complete resection with re-approximation of the proximal and distal vaginal mucosa can be accomplished.19 The description of this procedure can be found in alternate resources but essentially the idea to avoid tension when the vaginal mucosa is reapproximated is that the mucosa is resected radially to create a repair like shark teeth coming together to prevent strain along a single suture line. Complete excision of the septum beneath the vaginal mucosa is critical in prevention of vaginal stenosis. When the septum is thick greater than a centimeter a graft is often necessary to bridge the proximal and distal vagina, avoid tension and limit the risk of stenosis.

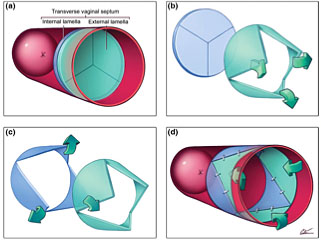

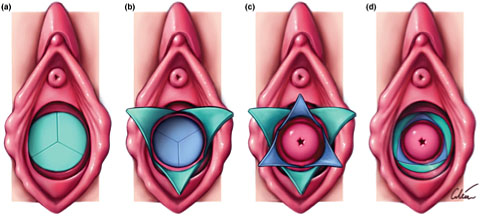

4

Demonstration of principle of Y-plasty technique: (a) Imperforate vaginal septum; note external and internal lamellae. Interstitial areolar tissue of variable thickness normally occupies interlamellar space. (b) Inverted Y-plasty on external lamella produces three external flaps; these will eventually be turned inwards. (c) Y-plasty on internal lamella produces three internal flaps; these are turned outwards. (d) External flaps are inverted and interdigitated with internal ones. Note zigzag pattern of resulting scar. Courtesy Cilein Kearns, studio.artibiotics.com.

5

Schematic diagram of vulva and vaginal canal before (a) and after (d) release of septum with interdigitating Y-plasty technique. Sequence (a) to (d) corresponds to the same steps as in Figure 1. Note cervix is not normally visible at the end of the procedure but has been included in the illustration to better demonstrate the concept of the technique. Courtesy Cilein Kearns, studio.artibiotics.com.19

Presurgical planning is important for not only the initial surgical intervention but also for patient involvement in their post-operative care, which is critical to success of the surgery. This procedure is at high risk for developing cervical stenosis postoperatively and repair and reconstruction becomes increasingly difficult. Initiation of dilator therapy in the early postoperative period is a crucial step in patient care. Prior to surgical management assessment of a patient’s readiness to participate regularly in postoperative dilation is imperative. Menstrual suppression until a patient is ready to engage in their postoperative care is generally employed.

Partial Vaginal Septum – Longitudinal or Transverse

Presentation

On exam of the vaginal canal visually a septum can be missed as the speculum displaces it along the vaginal wall. This can often happen in nulliparous patients who are sexually active as the dilating effect of intercourse has stretched the fenestration in the transverse septum or stretched the partial transverse septum. Hadad et al.17 noted in a retrospective study that 56.4% of patients were asymptomatic. On a bimanual exam a narrowing or stricture can sometimes be palpated. These partial vaginal septa will often present with postcoital bleeding or obstetric trauma as they can become avulsed from their attachment to the vaginal wall. If the presentation is nonurgent and the diagnosis is made by history or exam a plan for surgical management should be made to prevent a potential traumatic injury during future coital activity or vaginal birth.17

Obstructed Hemi-Vagina and Ipsilateral Renal Agenesis (OHVIRA Syndrome)

Anatomy

OHVIRA is a result of failure of midline fusion resulting in a longitudinal septum causing agenesis of a kidney, hemivagina, and uterine didelphys. There is a wide variability in presentation depending on the degree of abnormality in the upper genital tract and the patency of the septum to the obstructed side. The obstructed hemi vagina may be microperforate. Characteristically, this condition is associated with renal agenesis on the side of the obstructed vagina. 65% of cases are noted to be right sided.20

Epidemiology

The incidence of the condition is 1.1–3.5%.21 It is significantly higher in patients presenting with infertility and thought to be close to 25%.22

Presentation

Presentation can be variable. Frequently outflow obstruction symptoms are present with pain; however, the vaginal septum can be partial. The patient can have symptoms of prolonged menses, spotting, or bleeding between menses or foul-smelling discharge. These symptoms are secondary to the partial obstruction. They can also present with a pelvic infection secondary to the partial septum and accumulating menstrual efflux, which is secondarily infected.

Diagnosis

This is a challenging diagnosis to make especially if the septum is microperforate Patients are menstruating from the microperforate septum. Furthermore, the vaginal canal often looks normal on exam. Some patients with a perforate septum may have experienced a pregnancy and delivery through the patent side. Even on a vaginal speculum exam it can be easy to miss as the septum, which can be flush against the lateral side wall and only a single cervix, is visible. If there is a hematocolpos it can be palpable on a bimanual exam and imaging will reveal its presence. Knowledge that this condition is associated with renal agenesis and high index suspicion are often what leads to the diagnosis.

An ultrasound is generally adequate for diagnosing this anomaly and will reveal a lateral hematoclopos as well as a uterine didelphys.13

Management

Once the condition is diagnosed and confirmed by imaging, surgical management involves resecting the septum vaginally. The septum is identified and canulated this can be done with multiple techniques. One is the placement of a stay suture at the apex of the septum maintain orientation when the septum is incised and the hematocolpos drained.

If the septum is perforate and the opening can be identified either with direct visualization or vaginoscopy a pediatric Foley catheter can be passed through the fenestration and inflated for better delineation of the septum. Careful identification of the landmarks of the bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly as well as repetitive identification of the orientation of the surgical plane prevents injury to surrounding structures. Dissection of the septum can be done sharply or with cautery. With the hematocolpos accumulation the contralateral cervix can be significantly dilated and prone to injury so careful identification to its margins and avoidance during septum resection is paramount.

Ideally the entire septum is resected but if the anatomy is distorted and most of the septum has been resected to allow for menstrual egress a follow-up exam under anesthesia to resect any remaining septal tissue after the anatomy has returned to normal is also an acceptable adjunct to the initial management.

Hysteroscopy is rarely necessary during the initial management but may be helpful in defining the cavity of the previous obstructed horn.

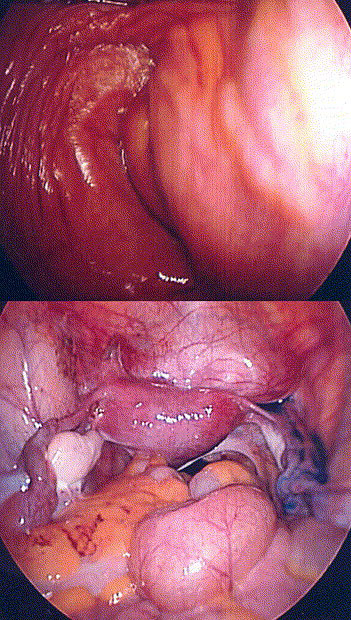

6

Top: A bulge in the left vaginal sidewall, with a single cervix visible at the apex. Bottom: Indigo carmine dye was instilled via the cervix and spilled only from the right fallopian tube. The bulging vaginal sidewall was then marsupialized, revealing a second cervix. Reproduced with permission from Wolters Kluwer.23

Vaginal Atresia

Anatomy

Vaginal atresia occurs when the urogenital sinus fails to invaginate resulting in an outflow obstruction and fibrous tissue in place of a vaginal canal. It is rare to occur in isolation and is often part of a syndrome such as Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser (MRKH).

Epidemiology

Congenital absence of the vagina or otherwise known as vagina aplasia is estimated to occur at an incidence of 1/4,000 live births.24

Presentation

Vaginal atresia is often associated with complete Mullerian aplasia or MRKH syndrome. However, there are a subset of patients that have variable presentations. Sometimes with just the lower portion of the vagina being atretic but a normal functional uterus and presentation is like any other obstructive anomaly.

Diagnosis

An ultrasound or MRI with careful attention to the distance between the cervix and perineum is helpful for counseling for management options. During an MRI a radiopaque vitamin E capsule can be placed between the labia and the perineum to help mark the distance from the cervix to the perineum and quantify the depth and length of the septum.

Management

Management is dependent on what functional tissue is present. In cases of complete vaginal atresia and a functional uterine cavity with a cervix vaginoplasty can be attempted. Development of a vaginal canal can be attempted with dilation or surgical management. In the absence of a functional uterine cavity or cervix management may also include a hysterectomy with concurrent vaginal construction. The management of this surgically complex condition should be managed by a specialty team and intervention is variable depending on the unique anatomic anomalies present in the patient.24 Menstrual suppression until a surgical management plan can be made is generally recommended.

UPPER GENITAL TRACT – CERVIX, UTERUS, FALLOPIAN TUBES, AND OVARIES

Cervical Agenesis

Anatomy

Cervical agenesis is extremely rare and is characterized by congenital absence of the cervix. The absence in the presence of a uterus is thought to be in part due to failed signaling from the invagination of the urogenital sinus.

Epidemiology

Conditions in which there is a partial development of the cervix are called cervical atresia or dysgenesis.6 In isolation, agenesis is rarer and estimated to be from 1/80,000–1/100,000.25 50% of cases are associated with congenital vaginal agenesis.25

Presentation

Presentation is like all obstructive anomalies with pain and hematometra or hematosalpinx. In the absence of a cervix or vagina a hematocolpos will not be present.

Diagnosis

An MRI is the primary modality for making this diagnosis. The differentiation between the lower uterine segment and the cervicovaginal junction can be difficult to appreciate by transabdominal ultrasound alone. The nuances come with discerning the location of the obstruction and whatever remnant tissue remains to best counsel the patient and family and plan management strategy.

Management

Cervical agenesis is in a spectrum with vaginal agenesis and management remains similar. In cases of isolated cervical agenesis and a functioning uterus multiple surgical interventions to recreate a cervix with a cerclage technique have been attempted. There are case reports in which highly experienced specialists who have achieved functional success for menstrual egress. However there have been many case reports of ascending infection, pelvic infection, multiple surgical interventions, chronic pain, and death. Given the high complication rate and frequent need for stage surgical interventions with inconsistent fertility outcomes many patients and families will decide on a hysterectomy.25 Like complete Mullerian agenesis where family building can be initiated through surrogacy or transplant. Menstrual suppression can be initiated as the medical decision-making process continues. It also allows the family and patient time to process this diagnosis and its consequences. Psychological support is a critical intervention for these patients and families due to the of impact on their fertility and identity.26

MULLERIAN AGENESIS (ALSO KNOWN AS MAYER–ROKITANSKY–KUSTER–HAUSER SYNDROME, MRKH, AND VAGINAL AGENESIS)

Complete Mullerian Agenesis

Anatomy

Mullerian agenesis can have a single midline uterine remnant, fibrous bands, atrophic uterine horns with and without functional endometrium. Uterine remnants both in the true pelvis as well as higher towards the pelvic brim near the ipsilateral ovary as a result from interrupted transit during development. 30% can have unilateral or bilateral abnormal location of the ovaries. Ovaries will be commonly found at the pelvic brim but have also been noted in the inguinal fossa.6 Fallopian tubes are generally absent or atrophic but occasionally fimbriae can be present. The cervix is absent. The vaginal canal is generally not present or present as a vaginal dimple. Occasionally there is some length to the lower third of the vagina, but the upper vagina is always absent. If a patient presents with pain consideration to either a septum or a partial uterine remnant with active endometrium should be given and will be differentiated by imaging the patient by MRI. Uterine remnants may be present in 75–95% of patients.6 Functional endometrium is generally not present in true Mullerian agenesis but if a rudimentary horn is present this raises the index of suspicion. Associated anomalies of the renal system such as aplastic or ectopic kidneys can also be associated, and imaging of the abdomen should be included.6

Finally, cardiac and skeletal anomalies are also associated in some forms of Mullerian agenesis and X-ray of the spine as well as an echocardiogram can be considered.

Epidemiology

Complete uterovaginal agenesis or Type 1 MRKH occurs in approximately 1/4,500–5,000 births.27 Upon presentation imaging of the abdomen and pelvis is warranted. This can be initiated with a pelvic ultrasound. A genotype and sex steroid hormones will complete the evaluation and differentiate these two diagnoses. Androgen insensitivity can also present in this way and will be elucidated with this evaluation as well. When the diagnosis has been confirmed referral to a specialty center for guidance of further care may be warranted. Up to 53% of patients with Mullerian agenesis will have other associated anomalies. 27–29% will have associated renal anomalies.27 Skeletal abnormalities will occur in 8–32%.27

Presentation

Complete Mullerian agenesis generally presents in adolescence with primary amenorrhea. These patients will proceed with normal pubertal change and can often be difficult to distinguish from other conditions such as gonadal dysgenesis, complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, vaginal septum or imperforate hymen and cervical agenesis. These are the gonadal dysgenesis and Mullerian agenesis are the two most common causes of primary amenorrhea.28

Diagnosis

MRI, which includes the pelvis and kidneys, offers the best medium for diagnosis. It is also best able to evaluate for any ectopic uterine tissue or remnants. Uterine remnants are present in 75–95% of Mullerian agenesis patients. 30% can have ectopic ovaries, which are not in the traditional anatomic position.6

Management

MRKH is managed primarily by initiating dilator therapy to elongate the vaginal dimple. Progressive dilation is performed at the vaginal introitus for 10–30 minutes twice daily to achieve a functional vaginal length.29 In studies the definition of function is frequently related to patients’ personal satisfaction but has also been compared with a physical measurement of approximately 7 cm. If anatomical length is used as the definition, then surgical management can be more successful. With traction vaginoplasty achieving the highest success whereas both split and full thickness skin graft procedures having the lowest successful outcomes and highest rate of complications.30

In a cross-sectional study measuring the female sexual index scores there was similar sexual function and quality of life scores between the surgically managed MRKH patients and the patients who vaginally dilated. As the risks of surgical management far outweigh the risks of dilator therapy this remains the gold standard of care for MRKH patients.31 A multicenter trial had similar findings further underscoring the recommendation of initiating dilator therapy as the first line for MRKH/vaginal aplasia patients.32

An integral part of management for these patients and their families would be to offer guidance in establishing psychological support. The implications for future fertility and personal identity can be deeply impactful and guidance through the process of diagnosis and treatment is critical to the health and well-being of these patients.33

Family building for these patients at this time would involve primarily surrogacy and adoption. Their ovaries are generally unaffected and in a fertility specialist who is comfortable with transabdominal oocyte retrieval this can be accomplished even before a functional vagina has been established. However, the developing field of uterine transplantation offers an option for patients who may strongly desire the experience of pregnancy. Currently the complication risk is significant and currently uterine transplant remains an experimental option.34

RESOURCES AND DILATOR LINKS

https://www.beautifulyoumrkh.org/

https://www.vuvatech.com/collections/magnetic-vaginal-dilators

https://www.intimaterose.com/blogs/pelvic-pain/vaginal-dilator-training-for-ais-and-mrkh-syndrome

Instruction for Dilation (Figure 7)

http://youngwomenshealth.org/2013/10/08/vaginal-dilator-instructions/

7

Intimate Rose https://www.intimaterose.com/blogs/pelvic-pain/vaginal-dilator-training-for-ais-and-mrkh-syndrome. OpenAccess.

UTERUS

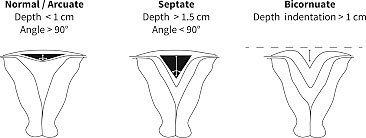

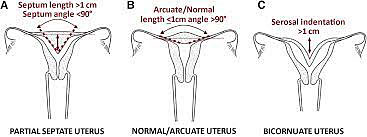

Uterine anomalies, excluding agenesis, are the result of either the failure of the Mullerian ducts to fuse in the midline or failure of canalization after the fusion of the Mullerian ducts. With near complete canalization the uterus may designated as arcuate or “sweetheart” shaped. This is considered a normal variant does not have any significant impact on fertility or obstetric outcome.35 The uterine anomalies associated with failure of complete canalization or fusion include unicornuate uterus, bicornuate uterus, and uterine didelphys. Diagnosis of the uterine anomalies generally presents in the setting of fertility management or following pregnancy loss. Ultrasound with or without the addition of a sonohysterogram or hysterosalpingogram is often sufficient to make the diagnosis. Occasionally an MRI is necessary to clarify the width and depth of a uterine septum or differentiate between this and a bicornuate as part of preoperative planning.36,37

In the case of a uterine septum, the most common uterine anomaly, term delivery rates are only approximately 5%. A hysteroscopic resection of the septum results in term delivery rates of approximately 75% and live birth rates of approximately 85%.38 A hysteroscopic approach to uterine septum resection is generally the preferred method. Most uterine septa are generally fibrous. Occasionally visualization with a laparoscope at the fundus can be helpful in determining the depth of resection at the fundus in thick wide fundal septa.39

Unicornuate Uterus and Unicornuate Uterus with a Uterine Remnant

Anatomy

A unicornuate uterus forms due to an absence of the contralateral horn or with an underdeveloped contralateral horn with residual uterine tissue. Unicornuate uterus can occur on either side of the pelvis and is often associated with an accompanying rudimentary horn, about 70%.6 It results in the failure of the development of a Mullerian duct and generally occurs between the seventh–eighth week of gestation.40 Poor obstetrical outcomes are associated with this anomaly there are several theories postulated for these poor outcomes, diminished muscle mass, abnormal blood supply, and cervical incompetence.41

Epidemiology

Unicornuate uterus is rare and occurs with an incidence of 0.6%.40 Obstetric complications associated with a unicornuate horn are significant. In a review by Reichman et al., they found that in patients with a unicornuate uterus 2.7% would experience an ectopic pregnancy, 24.3% a first-trimester abortion, 9.7% a second-trimester abortion, 20.1% preterm delivery, and 10.5% intrauterine fetal demise. In this review it was noted that only 49.9% had a live birth.40,41

Presentation

The unicornuate uterus is generally asymptomatic but can present with obstetric complications and is subsequently diagnosed with imaging. If a uterine remnant is present with functional endometrium the patient will generally present similarly to any other obstructive anomaly with pain and a hematometra if it is noncommunicating.

Diagnosis

An MRI is an important diagnostic tool for evaluating this condition as it will detect the presence of accessory tissue with better accuracy than an ultrasound. Particularly if the tissue is not entirely in the midline pelvis. Imaging for associated renal anomalies should be completed as 31–100% of these cases are accompanied by renal anomalies.6,41,42

Management

Management is dependent on the cause of presentation. If a patient presents with outflow obstruction symptoms from the noncommunicating horn, then menstrual suppression or surgical resection is recommended.6

Communicating or Noncommunicating Uterine Horns (Rudimentary Horn)

Anatomy

The rudimentary horn can be communicating with the patent unicornuate uterus or noncommunicating. It can have functional endometrium or not. Rudimentary horns associated with functional endometrium can present with symptoms of an obstructive anomaly.

Epidemiology

70% of unicornuate uteri are associated with a rudimentary horn. 40% are associated with renal anomalies.6

Presentation

This presentation can be more subtle as there is a patent uterine horn, so patients are often menstruating with cyclic pain. The diagnosis is often delayed with most patients presenting in their twenties.43

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is augmented with MRI; it is helpful in clarifying the relationship between the rudimentary horn and the functional uterine horn.

Management

Surgical management of the accessory horn is the mainstay of therapy. An accessory, noncommunicating horn with functional endometrium should be resected.

Treatment is recommended due to dysmenorrhea, menstrual efflux, placing a patient at risk for endometriosis. Surgery can generally be completed laparoscopically.

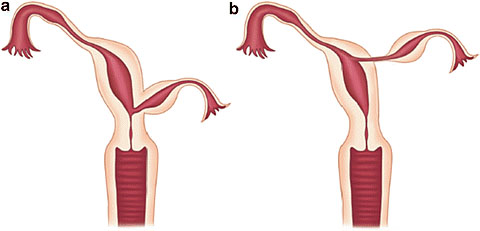

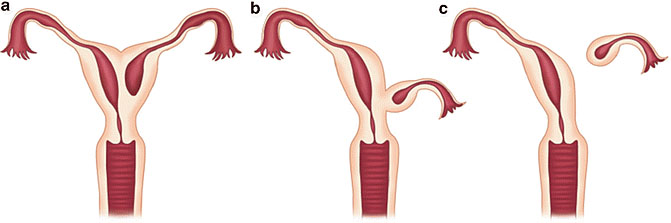

8

Communicating rudimentary horns. Nonseparated (a) and separated (b). OpenAccess.

9

Noncommunicating rudimentary horns with functional endometrium. Nonseparated (a), (b) and separated (c).44 OpenAccess.

Uterus didelphys

- Uterus didelphys with longitudinal septum.

- Uterus didelphys with longitudinal septum of variable length.

Anatomy

Uterus didelphys is the failure of midline fusion. It is frequently associated with a longitudinal vaginal septum, approximately 75%. The septum is often what triggers the diagnosis either by examination or by trauma during intercourse of vaginal delivery. If one of the uterine horns is obstructed or partially obstructed menstrual flow can be altered and can often present as chronic discharge if patent of cyclic pain as in obstructive anomalies if not patent. This condition is often associated with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis (OHVIRA), which is discussed elsewhere. The condition generally involves two complete uterine horns and cervices (bicollis) with or without a longitudinal vaginal septum. 15–20% have unilateral anomalies such as OHVIRA. The anomalies are found to be right sided in 65% of patients.45

Epidemiology

Obstetric complications, like in the unicornuate uterus are high. 32% will experience a spontaneous abortion. 28% will have preterm birth.46

Presentation

Patients present with an outflow obstruction if the septum is not patent, complications with the septum or with obstetric complications. If the septum is patent on both sides then patient often will have an incidental finding on exam, or complications from using menstrual products like tampons where the nonoccluded side will leak despite the placement of a tampon. Avulsion of the septum with tampon use or first intercourse can also occur. Obstetrical laceration of the septum when not previously diagnosed can also occur. Significant bleeding can occur with the avulsion of the septum and resection is generally recommended after diagnosis.

Diagnosis

This diagnosis is best imaged using an MRI.6

Management

Treatment is aimed at the resection of the longitudinal septum if present. At this time surgically unifying the uterine horns is not recommended as there is no evidence to support improved obstetric outcome.

Bicornuate

Anatomy

Bicornuate uterus is often an incidental finding. It can be differentiated from septate and arcuate uteri by the serosal indentation. A serosal indentation at the fundus >1 cm is consistent with a bicornuate uterus. Unlike a didelphys uterus the bicornuate has just two uterine horns not a completely duplicated system. Generally, there is one cervix and a single vaginal lumen. This condition results from a partial fusion of the Mullerian ducts.47

Epidemiology

Obstetrical complications include increased risk of spontaneous abortion at 36%, preterm birth at 21–23% risk. Survival rates for pregnancies from a bicornuate uterus are 50–60%.47

Presentation

Obstetric complications and incidental finding on imaging.

Diagnosis

Either a 3D ultrasound or MRI are best for making the diagnosis and measuring the serosal indentation at the fundus.6

Management

In patients with previous poor obstetric outcomes metroplasty has been attempted. There is also an association with cervical insufficiency, which likely contributes to the obstetric outcomes. Consideration to monitoring cervical lengths in pregnancies with bicornuate uteri should be considered. In a study by Maneschi et al.48 obstetric outcome was not significantly different after metroplasty, a live birth was a good prognostic indicator and increased the likelihood of subsequent live births.48

10

Uterine septum. Courtesy ASRM..39

11

Uterine septum. Courtesy ASRM.6

Arcuate

Anatomy

An arcuate uterus is considered a normal variant. It does not have any significant impact on fertility or obstetric outcome.49

Epidemiology

Arcuate uteri are common and suspected to affect 3.9% of all women. The prevalence is not increased in infertile women or in women with miscarriage.50

Presentation

Generally, an incidental finding.

Diagnosis

It can be diagnosed with 3D ultrasound and can be differentiated from a septate uterus by the intra-cornual line being >1 cm and the angle of the septum greater than 90 degrees.51

Management

No management required.

Septate/Subseptate

Anatomy

In a septate uterus there is failed canalization or fusion. The septum can be partial, complete, or extend through the cervix and vagina.

Epidemiology

The septate uterus is the most common uterine anomaly with estimates between 35–90% of all identified malformations. The septate uterus has poor obstetrical outcome. Patients with septate uterus have spontaneous abortion rates of 21–44% and preterm birth 12–33%. The live birth rate is 50–72%. Breech presentation and placental abruption are also often seen with this condition.52

Presentation

Septate uterus is generally found on evaluation for infertility, recurrent miscarriage, or another poor obstetric outcome.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is generally made via 3D ultrasound and sonohysterogram ultrasound.

Management

Treatment for a uterine septum is a hysteroscopic resection and prevention of adhesions the postoperatively.

ANOMALIES OF THE UPPER GENITAL TRACT

Ovaries

Anatomy

The ovary is commonly found above the pelvic brim. In cases of a normally positioned but single ovary this may be a result of autolysis of an ovary that was torsed when the patient was an infant or child.53,54,55

Epidemiology

Allen et al. reported 17% associated with uterine anomalies as compared to 3% in women with normal anomaly.56

Presentation

Ovarian maldescent is rare and often an incidental finding. It is associated with other upper genital tract anomalies, including uterine didelphys, unicornuate, and bicornuate uteri.56,57

Diagnosis

Often an incidental finding and noted on imaging medium used for presenting condition.

Management

None.

Fallopian Tubes

Anatomy

Fallopian tube agenesis has been reported in conjunction with unilateral absence of an ovary. No syndromes have been associated with this condition. It is thought that perhaps this is related more to an in utero, neonatal, or early life vascular disruption. The absence of a single fallopian tube has been postulated to occur in cases of torsion in utero and early life.54,57,58

Epidemiology

There are rare case reports for isolated absence of the fallopian tubes.

Presentation

Incidental finding.

Diagnosis

Incidental finding.

Management

None.

SEQUELAE OF MULLERIAN ANOMALIES

Infertility

Uterine anomalies are 21 times more likely to occur in women with infertility.41 Patients with Mullerian anomalies often have trouble with conception. The prevalence of Mullerian anomalies in women presenting with infertility is 8%, rising to 13% in women with a history of pregnancy loss.51

Endometriosis

Long-term consequences of reproductive anomalies often focus on fertility outcomes. However, dysmenorrhea and endometriosis are chronic complications associated with especially the obstructive anomalies that do not always resolve with the initial management. This is thought to be directly related to the menstrual reflux into the peritoneal cavity. Although not indicated with initial management, if patients have persistent dysmenorrhea after corrective intervention, especially if their symptoms are resistant to medical management, an evaluation for endometriosis is warranted. Silveira et al. noted that patients presenting as early as 6 months but up to 5 years after their primary management presented with all stages of endometriosis.59 Interestingly, Sanfillipo et al.60 reported a case where endometriosis was noted to regress after surgical correction, which begs the question of inherent risk in the process that caused the anomaly during fetal development.60. As this remains an area of developing knowledge, it is still not routine to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy at the time of the initial corrective procedure for the single purpose of diagnosis of endometriosis. Education of the patient and family of this as a possibility and encouraging a menstrual and symptom diary as well as close follow up can often facilitate early presentation, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis and its sequelae.

Complications in Pregnancy

In a meta-analysis of 47 studies by comparing patients with and without uterine anomalies, the estimated risks for obstetric related outcomes were analyzed. In general, compared to women with unaffected uteri having an anomaly did increase risk of birth before 37 weeks, fetal malpresentation, pre-labor rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, placental abruption, cervical insufficiency, placenta previa, placental retention, and cesarean birth. Delivering a small for gestational age infant or low birth weight infant was also more likely in women with a uterine anomaly versus a normal uterus. Risks for preterm labor, malpresentation, fetal growth restriction all seem to be related to uterine cavity size and are more common in septate, bicornuate, didelphys, and hemi uteri. Abnormal uterine contractility is also suspected to contribute to the obstetric outcomes as well as contribute to increased cesarean section risk. The low birth weight and small for gestational age outcomes were not analyzed specifically for age at delivery so may reflect prematurity. The highest risk for placental abruption occurred in septate uteri. Septate uteri were also associated with higher risk of placenta previa and retained placenta compared to other uterine anomalies and normal uteri. When including all uterine anomalies there is significant increased risk in obstetric outcomes.61 Pangiotopoulos et al.61 recorded cumulative risks of 25% for preterm birth, 40% for fetal malpresentation, 64% for cesarean birth, 12% for premature rupture of membranes, 15% for fetal growth restriction, 4% for placental abruption 5% for pre-eclampsia, 13% for cervical insufficiency, and 2% for placenta previa.61

SUMMARY

In summary, the development, consequences, and management of reproductive tract anomalies are complex. Most conditions can be identified and diagnosed by the physician that first engages the patient. Clarifying the diagnosis with imaging, offering counsel, comfort, and menstrual suppression can often be the most significant initial interventions.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- For patients presenting with an obstructive anomaly pain management and supportive care is the priority. Urgent surgical management is not needed and not recommended.

- Complex anomalies should be managed by providers familiar with these conditions when possible.

- Psychological support should be made available when poor fertility outcomes are part of the diagnosis, such as in Mullerian agenesis.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Oppelt P, von Have M, Paulsen M, et al. Female genital malformations and their associated abnormalities. Fertil Steril 2007;87(2):335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1501. Epub 2006 Nov 27. PMID: 17126338. | |

Cunha GR, Robboy SJ, Kurita T, et al. Development of the human female reproductive tract. Differentiation 2018;103:46–65. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 6. PMID: 30236463; PMCID: PMC6234064. | |

National Cancer Institute 12/2021, Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Exposure and Cancer, (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/des-fact-sheet). | |

Surrey ES, Katz-Jaffe M, Surrey RL, et al. Arcuate uterus: is there an impact on in vitro fertilization outcomes after euploid embryo transfer? Fertil Steril 2018;109(4):638–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.001. Epub 2018 Mar 30. PMID: 29609956. | |

Connell M, Owen C, Segars J. Genetic Syndromes and Genes Involved in the Development of the Female Reproductive Tract: A Possible Role for Gene Therapy. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2013;4:127. doi:10.4172/2157-7412.1000127. | |

Pfeifer SM, Attaran M, Goldstein J, et al. ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertil Steril 2021;116(5):1238–52. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.09.025. PMID: 34756327. | |

Debiec KE, Amies Oelschlager AE. Uterovaginal Anomalies: A Guide for the Generalist Obstetrician-Gynecologist. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2020;63(3):512–27. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000542. PMID: 32452844. | |

Management of Acute Obstructive Uterovaginal Anomalies: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 779. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(6):e363–71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003281. PMID: 31135762. | |

Wong JWH, Siarezi S. The Dangers of Hymenotomy for Imperforate Hymen: A Case of Iatrogenic Pelvic Inflammatory Disease with Pyosalpinx. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2019;32(4):432–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.04.002. Epub 2019 Apr 9. PMID: 30974214. | |

Olive DL, Henderson DY. Endometriosis and Mullerian anomalies. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69(3 Pt 1):412–5. PMID: 3822289. | |

O'Flynn O'Brien KL, Bhatia V, Homafar M, et al. The Prevalence of Müllerian Anomalies in Women with a Diagnosed Renal Anomaly. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2021;34(2):154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.11.015. Epub 2020 Nov 23. PMID: 33242594. | |

Diagnosis and Management of Hymenal Variants: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 780. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(6):e372–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003283. PMID: 31135763. | |

Smith NA, Laufer MR. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome: management and follow-up. Fertil Steril 2007;87(4):918–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.015. Epub 2007 Feb 22. PMID: 17320871. | |

Watrowski R, Jäger C, Gerber M, et al. Hymenal anomalies in twins–review of the literature and case report. Eur J Pediatr 2014;173(11):1407–12. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2123-3. Epub 2013 Aug 11. PMID: 23933671. | |

Copyright – all rights reserved. Clifford R Wheeless Jr, MD and Marcella L. Roenneburg MD. All contents of this web site are copywrite protected. http://www.atlasofpelvicsurgery.com/aopssitemap.html]. | |

Bermejo C, Martínez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;35(5):593–601. doi: 10.1002/uog.7551. PMID: 20052665. | |

Haddad B, Louis-Sylvestre C, Poitout P, et al. Longitudinal vaginal septum: a retrospective study of 202 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997;74(2):197–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00105-x. PMID: 9306118. | |

Alaniz VI, Quint EH. Transverse Vaginal Septum. In: Pfeifer S. (eds.) Congenital Müllerian Anomalies. Springer, Cham, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27231-3_4). | |

Arkoulis N, Kearns C, Deeny M, et al. The interdigitating Y-plasty procedure for the correction of transverse vaginal septa. BJOG 2017;124(2):331–5. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14228. Epub 2016 Jul 25. PMID: 27457120. | |

Vercellini P, Daguati R, Somigliana E, et al. Asymmetric lateral distribution of obstructed hemivagina and renal agenesis in women with uterus didelphys: institutional case series and a systematic literature review. Fertil Steril 2007;87(4):719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.173. PMID: 17430731. | |

Strassmann EO. Fertility and unification of double uterus. Fertil Steril 1966;17(2):165–76. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)35882-4. PMID: 5907041. | |

Acién P, Acién M. The presentation and management of complex female genital malformations. Hum Reprod Update 2016;22(1):48–69. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv048. Epub 2015 Nov 3. PMID: 26537987. | |

Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, Hendren WH. Structural abnormalities of the female reproductive tract. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, eds. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology (5th edition). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishing Company, 2005: 405, Fig 10-98. 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. | |

Creatsas G, Deligeoroglou E. Vaginal aplasia and reconstruction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010;24(2):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.11.002. Epub 2010 Jan 20. PMID: 20089458. | |

Mikos T, Gordts S, Grimbizis GF. Current knowledge about the management of congenital cervical malformations: a literature review. Fertil Steril 2020;113(4):723–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.02.006. PMID: 32228875. | |

Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive reproductive tract anomalies. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27(6):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.09.001. Epub 2014 Sep 11. PMID: 25438708. | |

Aittom€aki K, Eroila H, Kajanoja P. A population-based study of the incidence of Mullerian aplasia in Finland. Fertil Steril 2001;76:624. | |

Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive müllerian anomalies. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27(6):386–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.001. Epub 2014 Jul 17. PMID: 25438707. | |

Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 728: Müllerian Agenesis: Diagnosis, Management, And Treatment. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131(1):e35–42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002458. PMID: 29266078. | |

Callens N, De Cuypere G, De Sutter P, et al. An update on surgical and non-surgical treatments for vaginal hypoplasia. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:775–801. | |

Kang J, Chen N, Song S, et al. Sexual function and quality of life after the creation of a neovagina in women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome: comparison of vaginal dilation and surgical procedures. Fertil Steril 2020;113(5):1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.01.017. PMID: 32386614. | |

Cheikhelard A, Bidet M, Baptiste A, et al.; French MRKH Study Group. Surgery is not superior to dilation for the management of vaginal agenesis in Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome: a multicenter comparative observational study in 131 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219(3):281.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.07.015. Epub 2018 Jul 21. PMID: 30036500.). | |

Kaplan EH. Congenital absence of the vagina. Psychoanal Q 1970;39(1):52–70. PMID: 5413147. | |

Jones BP, Saso S, Bracewell-Milnes T, et al. Human uterine transplantation: a review of outcomes from the first 45 cases. BJOG 2019;126(11):1310–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15863. Epub 2019 Aug 13. PMID: 31410987. | |

Surrey ES, Katz-Jaffe M, Surrey RL, et al. Arcuate uterus: is there an impact on in vitro fertilization outcomes after euploid embryo transfer? Fertil Steril 2018;109(4):638–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.001. Epub 2018 Mar 30. PMID: 29609956. | |

Rivas AG, Epelman M, Ellsworth PI, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of Müllerian anomalies in girls: concepts and controversies. Pediatr Radiol 2022;52(2):200–16. doi: 10.1007/s00247-021-05089-6. Epub 2021 Jun 21. PMID: 34152437. | |

Acharya PT, Ponrartana S, Lai L, et al. Imaging of congenital genitourinary anomalies. Pediatr Radiol 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00247-021-05217-2. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34741177. | |

Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, et al. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7(2):161–74. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.161. PMID: 11284660. | |

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address: ASRM@asrm.org; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Uterine septum: a guideline. Fertil Steril 2016;106(3):530–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.014. Epub 2016 May 25. PMID: 27235766. | |

Raga F, Bauset C, Remohi J, et al. Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies. Hum Reprod 1997;12(10):2277–81. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.10.2277. PMID: 9402295. | |

Reichman D, Laufer MR, Robinson BK. Pregnancy outcomes in unicornuate uteri: a review. Fertil Steril 2009;91(5):1886–94. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.163. Epub 2008 Apr 25. Erratum in: Fertil Steril 2015;103(6):1615-8. PMID: 18439594. | |

McCracken K, Hertweck SP. Noncommunicating Rudimentary Uterine Horns. In: Pfeifer S. (eds.) Congenital Müllerian Anomalies. Springer, Cham, 2016. | |

Jayasinghe Y, Rane A, Stalewski H, et al. The presentation and early diagnosis of the rudimentary uterine horn. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1456–67. | |

McCracken K, Hertweck SP (Noncommunicating Rudimentary Uterine Horns. In: Pfeifer S. (eds.) Congenital Müllerian Anomalies. Springer, Cham, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27231-3_11] | |

Vercellini P, Daguati R, Somigliana E, et al. Asymmetric lateral distribution of obstructed hemivagina and renal agenesis in women with uterus didelphys: institutional case series and a systematic literature review. Fertil Steril 2007;87(4):719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.173. PMID: 17430731. | |

Venetis CA, Papadopoulos SP, Campo R, et al. Clinical implications of congenital uterine anomalies: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Reprod Biomed Online 2014;29(6):665–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.09.006. | |

Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, et al. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7(2):161–74. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.161. PMID: 11284660. | |

Maneschi F, Marana R, Muzii L, et al. Reproductive performance in women with bicornuate uterus. Acta Eur Fertil 1993;24(3):117–20. PMID: 7985453. | |

Hua M, Odibo AO, Longman RE, et al. Congenital uterine anomalies and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205(6):558.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.022. Epub 2011 Jul 22. PMID: 21907963. | |

Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, et al. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17(6):761–71. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr028. Epub 2011 Jun 24. PMID: 21705770; PMCID: PMC3191936. | |

Ludwin A, Martins WP, Nastri CO, et al. Congenital Uterine Malformation by Experts (CUME): better criteria for distinguishing between normal/arcuate and septate uterus? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51(1):101–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.18923. Erratum in: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51(2):282. PMID: 29024135. | |

Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, et al. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7(2):161–74. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.161. PMID: 11284660. | |

Paternoster DM, Costantini W, Uglietti A, et al. Congenital or torsion-induced absence of Fallopian tubes. Two case reports. Minerva Ginecol 1998;50(5):191–4. PMID: 9677808. | |

Uckuyu A, Ozcimen EE, Sevinc Ciftci FC. Unilateral congenital ovarian and partial tubal absence: report of four cases with review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2009;91(3):936.e5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.022. Epub 2008 Nov 1. PMID: 18976994. | |

Pabuccu E, Kahraman K, Task?n S, et al. Unilateral absence of fallopian tube and ovary in an infertile patient. Fertil Steril 2011;96(1):e55–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.027. Epub 2011 May 11. PMID: 21561606.). | |

Allen JW, Cardall S, Kittijarukhajorn M, et al. Incidence of ovarian maldescent in women with mullerian duct anomalies: evaluation by MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198(4):W381–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6595. PMID: 22451577. | |

Verkauf BS, Bernhisel MA. Ovarian maldescent. Fertil Steril 1996;65(1):189–92. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58050-9. PMID: 8557139. | |

Paternoster DM, Costantini W, Uglietti A, et al. Congenital or torsion-induced absence of Fallopian tubes. Two case reports. Minerva Ginecol 1998;50(5):191–4. PMID: 9677808. | |

Silveira SA, Laufer MR. Persistence of endometriosis after correction of an obstructed reproductive tract anomaly. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26:e93. | |

Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, et al. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;154:39. | |

Panagiotopoulos M, Tseke P, Michala L. Obstetric Complications in Women With Congenital Uterine Anomalies According to the 2013 European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy Classification: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139(1):138–48. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004627. PMID: 34856567. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)