This chapter should be cited as follows:

Hanson C, Moller A-B, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415343

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 2

Health and risk in pregnancy and childbirth

Volume Editors:

Professor Claudia Hanson, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

Dr Nicola Vousden, King’s College, London, UK

Chapter

Global Maternal and Perinatal Health Indicators in the Context of the Sustainable Development Goals

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

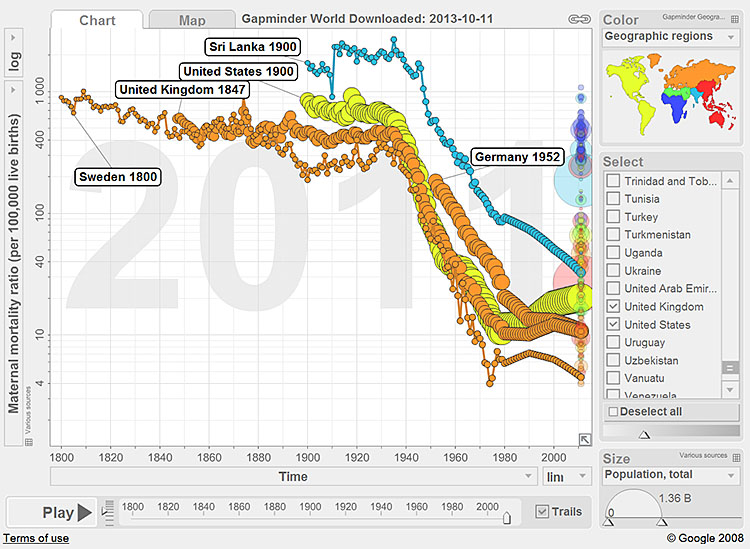

Sweden was the first country in the world to document all births and deaths, and among them maternal deaths (Figure 1).1 The unique documentation and compilation based on parishes was facilitated by Sweden having only one religion, a culture of trust and strong administrative structures. Maternal mortality levels above 1000 per 100,000 live births were described in 1750 to 1850 after which mortality slowly started to decline. Other countries that started to document maternal mortality are the United Kingdom and the United States where statistics are available from the late 1880s.2 It is important to note that these first reports of maternal mortality included only deaths from direct obstetric causes and not indirect maternal deaths. Thus, deaths due to malaria or anemia are underlying reasons of maternal deaths were excluded (Box 1).3 This is why we have seen historically even higher maternal mortality ratios in some low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) than were ever reported from Western countries.4

1

Historical trends of maternal mortality in Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States and Sri Lanka.

Box 1 Maternal and perinatal measurements

According to the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) which was adopted in 1994 Maternal Mortality is defined as a death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of pregnancy, from any cause related or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.5 ICD-11 has been released, but the transition will take time.

Maternal mortality can be due to direct obstetric causes (hypertensive disorders, obstetric hemorrhage, abortion or puerperal sepsis) and indirect non-obstetric causes which are conditions that are aggravated during pregnancy (e.g. anemia or malaria). HIV in pregnancy may be coded as a maternal death if the conditions worsened because of the pregnancy. However, HIV/AIDS can also be coincidental describing a situation where a women died from her HIV infection and coincidentally she was pregnant. In 2012, WHO published a guideline to give more concrete indications of how to code maternal deaths defining eight main codes instead of the detailed ICD-10 codes which can be very difficult to use in settings where a detailed diagnosis is constrained by the lack of diagnostic options called ICD-MM.6

WHO has provided periodic updates of maternal mortality estimates since the year 2000, the most recent were published in 2019.7 These estimates are based on available country data but adjusted for underreporting (i.e. misclassified, missed and unregistered deaths) depending on the methods used. For example, maternal mortality ratio derived from

civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) may be inflated to adjust for misclassification. Data from DHS or MICS using the sisterhood method are adjusted downwards as data report pregnancy-related deaths, thus including accidental and incidental causes and adjusted upwards to compensate for underreporting of deaths, particular early pregnancy and abortion-related mortality.

The following indicators are used::8

Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) – number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period.

Maternal Mortality Rate (MM-rate) – number of maternal deaths divided by person-years lived by women of reproductive age.

Adult lifetime risk of maternal death – the probability that a 15-year-old woman will die eventually from a maternal cause.

A neonatal death is defined as a death during the first 28 days of life.

Neonatal mortality rate – number of deaths in the first 28 days of life (0–27 days), expressed per 1000 live births.9

Stillbirths can occur antepartum or intrapartum. In many cases, stillbirths reflect inadequacies in antenatal care coverage or in intrapartum care. For purposes of international comparison, stillbirths are defined as third trimester fetal deaths (≥1000 g or ≥28 weeks). ICD-11 will set the cut-off level at ≥28 weeks. The stillbirth rate is expressed as the number of stillbirths per 1000 total births.9 Perinatal mortality rate is defined as stillbirths and neonatal deaths in the first 7 days of life, expressed per 1000 total births (live and stillbirths).

International recognition of maternal mortality started with the League of Nations, established in 1919, as the organization that paved the way to the installment of the United Nations structure and the establishment of World Health Organization (WHO) in 1949. However, it took another 40 years to convene the first Safe Motherhood Conference in 1987 in Nairobi, Kenya, to put maternal mortality on the international agenda10 and to release a first global published compilation of maternal mortality estimates.11 This first compilation was followed by regular updates prepared since the 2000s by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Interagency Group (MMEIG) composed of WHO, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Later joined by the United Nations Population Division, and the World Bank Group. The MMEIG is tasked with developing internationally comparable estimates of maternal mortality for the purposes of global monitoring, having done so for Millennium Development Goal reporting and now for the Sustainable Development Goals.4,12,13,8 The most recent estimates for maternal mortality were published September 2019.7 Measuring maternal health is, however, always constrained by the fact that maternal mortality is a rare event in epidemiological terms and difficult to measure in countries where no civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) system documenting all births and deaths is established.

METHODS TO DERIVE MATERNAL MORTALITY ESTIMATES

The first global data on maternal mortality from LMICs were compiled from hospitals.11 The first population-based data of maternal mortality became available in the 1990s after the milestone publication from Wendy Graham proposing the sisterhood method to derive maternal mortality estimates.14 The sisterhood method included interviews of women of reproductive age of about deaths in sisters in population-based surveys. The method assumed that sisters keep close contact throughout their life and that the circumstances of death (thus whether the deaths was pregnancy-related) is known to sisters.14,15 This method has been, with some modification, employed in nationally representative household surveys such as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) since the late 1990s.16 While these data are imperfect, as they come with large uncertainty and relate typically to a period of 7–10 years prior to the survey, they are the cornerstone of maternal mortality estimates in many LMIC still today.

A few countries have included the measurement of maternal mortality in national censuses.17,18 While censuses provide the opportunity to derive sub-national estimates of maternal mortality, the quality of data have been debated as it is difficult to maintain sufficient quality in the interview process.19

CRVS systems with death certification by a medical professional are seen as the best method to ascertain maternal deaths.20,21 Misclassification, but also missed or unregistered maternal deaths are however common even in countries with good quality and complete CRVS.7,22,23,24 In most LMICs, CRVS systems are either not yet established or incomplete – although major investments are under way. A major driver for improving CRVS may be the inclusion of CRVS in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets (Goal 16, see Box 2). Health and Demographic Surveillance Sites (HDSS) use the same principle as CRVS that every birth and death is continuously recorded but in a defined population of typically less than 100,000 people. This defined population is visited at regular intervals, commonly twice or three times a year. Information on births, deaths, and migration is regularly documented and the causes of death are derived from verbal autopsies which are interviews establishing the circumstances of the deaths by interviewing a family member of the deceased.25,26 Other data sources for maternal mortality are Reproductive Age Mortality Studies (RAMOS) where all deaths in women of reproductive age are analyzed. Multiple and diverse sources to identify all deaths in women of reproductive age are included and triangulated.8

Box 2 Key Sustainable Development Goals indicator linking to maternal, perinatal and reproductive health27

SDG 3 Good health and well-being

- By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births

- By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1000 live births

- By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes

- Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

SDG 2 Zero hunger

- By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons.

SDG 5 Gender equality

- End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere

- Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

- Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation.

SDG 6 Clean water and sanitation

- By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.

SDG 16 Peace, justice and strong institutions

- By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration.

MONITORING OF PERINATAL AND NEONATAL MORTALITY

While systematic documentation of child mortality has received attention since the mid-1900s, the first unpublished compilation of perinatal mortality, stillbirths and neonatal deaths was only prepared in 1996 by WHO.28 The first Lancet series on Neonatal Survival was published in 200529 and the large burden of stillbirth was first quantified in 2006.30 Neonatal mortality has received increasing attention with the recognition of the high proportion of under-five mortality that occurs during the neonatal period. In 2018, it was estimated that 47% of the 5.4 million child deaths in 2017 occurred in the first 28 days of life.31

Measuring neonatal mortality is substantially easier than measuring maternal mortality for several reasons. First, there are many more neonatal deaths, so from an epidemiological perspective, fewer deaths need to be included to derive precise estimates. In addition, most of the time the mother survives the loss of her child and can report on the event in household surveys. In DHS and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)32 women of reproductive age are interviewed about all births and deaths in children. If a child has died, date of death is documented which is then used to define whether the child died in the neonatal period. However, misclassification as well as missed and unregistered deaths is a concern, particular in societies where the death on a neonate is perceived as shameful..33 Cultural issues of blame and fear may be even a larger issue around stillbirths.34 In part, problems relate to definitions and the fact that many stillbirths are not weighed, gestational age is not assessed, and thus the differentiation between early neonatal deaths and stillbirth cannot be made. In addition, due to entrenched cultural beliefs, many women and communities do not like to talk about pregnancy losses and household surveys do not routinely capture stillbirths (see more Box 1)..33

KEY MEASUREMENTS FOR MONITORING MATERNAL HEALTH IN THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOAL PERIOD

The goal of reducing maternal mortality by 75% within 25 years was articulated as the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) – target 5.A in the year 2000.35 This translates to an annual rate of reduction in mortality of 5%. Prior to this there had been a number of previous statements and published goals. At the first Safe Motherhood conference in Nairobi in 1987 a target to halve maternal deaths between 1990 and 2000 and to halve them again between 2000 and 2015 was set. Both the 1994 International Conference of Population and Development36 and the 1995 World Conference on Women held in Beijing, endorsed this goal.37 They are noteworthy for their ambitious targets given that maternal mortality had not changed in the preceding 30 years.

With the release of the MDGs monitoring framework another indicator became important for monitoring maternal health and related to universal access to reproductive health measured by birth with a ‘skilled birth attendant’. In view of the measurement issues around maternal mortality this proxy indicator was deemed most appropriate to complement the global monitoring of maternal mortality. This indicator also reflected the policy shift in the 1990s, where the approach of home deliveries with trained traditional birth attendants for low-risk births was replaced by a strategy of providing all women with an appropriately trained skilled birth attendant – a strategy which was backed by several country analyses38 and supported by the slogan “every pregnancy faces risk”.39 In 2004 the first definition of a skilled birth attendant was published stating a skilled birth attendant as a health care provider being trained to proficiency.40 In most countries all formal health providers, doctors, nurses and midwives were thus counted as being skilled birth attendants. In some countries also auxiliary nurses were included. By the end of the MDG period major progress has been reported in the proportion of births attended by a skilled birth attendant.41 There are several low-income countries today reporting levels above 80%, even in very low income countries like Malawi.42 However, as uptake of facility delivery and birth with a skilled birth attendant increased, the indicator became more and more debated as maternal mortality reduction was only moderate even in countries with large improvements in birth with a skilled birth attendant.43 In 2018, WHO, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the International Pediatric Association (IPA) published a new definition of what skilled health personnel providing care during childbirth should be able to know and do.44

In 2006, the target 5.B: to achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health was added to complement the maternal mortality and skilled attendant indicators. Subsequently the MDG monitoring also included (i) the contraceptive prevalence rate, (ii) the unmet need for family planning. (iii) antenatal care (at least one/at least four visits) coverage, and (iv) adolescent birth rate. The indicators of contraceptive prevalence and the unmet need for family planning linked back to the indicators of population health and fertility which were first set at the International Conferences of Development and Populations in the 1980s and 1990s.36

Although the two indicators of family planning (contraceptive prevalence and the unmet need for family planning) were added in 2006, funds and attention to family planning was very limited throughout the first decade of the 2000s.45 With the Summit on Family Planning in 201246 and the launch of the Family Planning 2020, programming and also measurement of progress of family planning regained attention. The Family Planning 2020 initiative regularly compiles 18 indicators among them indicators of access like the modern contraceptive prevalence rate and demand satisfied and indicators of quality like method availability, stock-outs and counseling.47

In parallel to the establishment of the skilled birth attendant indicator the first draft of the Emergency Obstetric Care (EmOC) indicators was published in 1997.48 The EmOC indicators have become a well-known concept to monitor maternal health programs.49 A large number of EmOC assessments have been done by international agencies, foremost the UNFPA together with the Averting Maternal Death and Disability program.49,50,51,52,53 However, this indicator set was never unanimously supported54 and it remains questionable whether facilities with a low case load can be judged on their ability to provide care using the signal functions suggested.

MONITORING OF MATERNAL HEALTH WITHIN THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL CONTEXT

Key indicators to monitor progress

With the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)27 in 2015, countries have renewed their commitment to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 and ensure that no country has a maternal mortality ratio of over 140 as countries with high MMR will not be able to reduce to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births (Box 2). In addition, the goal to “ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services”, including family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs has been put forward.

The SDG maternal health goals are complemented by several targets within the SDG goals 2, 5, 6 and 16 where a direct link to maternal and reproductive health is made (Box 2). This is an important recognition of sectors other than health that can make major contributions to support maternal and reproductive health such as gender equality, water and sanitation as well as the documentation of births and deaths.

The SDG agenda is supported by several global initiatives and strategies such as the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health (Global Strategy),55 Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP),56 Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM),57 and the Global Financing Facility in Support of Every Woman Every Child58 initiative. Each of these global initiatives have put forward indicators to monitor progress. While there is some overlap, the different initiatives also propose many new indicators which are only partly validated and actually measured. A recent review of maternal and newborn health indicators mapped over 140 indicators of which 104 are regularly used in the monitoring of maternal and newborn health.59

The EPMM initiative has been key to outlining the main targets for maternal health for the post-2015 time.60 EPMM developed a set of indicators in two phases. The first phase identified indicators related to the proximal causes of maternal mortality, and the second phase build consensus on a set of indicators that capture information on the social, political, and economic determinants of maternal health and mortality. A total of 150 experts from more than 78 organizations worldwide participated in this second phase that finally mapped out 11 key themes and ultimately reached consensus on a set of 25 indicators (Table 1).61

1

Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM) indicators.61

EPMM I | EPMM II | Sustainable Development Goal or Global Strategy indicator |

Impact | ||

Maternal mortality ratio | √ | |

Maternal cause of death (direct/indirect) based on ICD-MM | √ | |

Adolescent birth rate | √ | |

Gender parity index (GPI) | √ | |

Outcomes/Coverage | ||

Four or more antenatal care visits | √ | |

Skilled attendant at birth | √ | |

Institutional delivery | √ | |

Early postpartum care for women and baby | √ | |

Met need for family planning | √ | |

Uterotonic immediately after birth | √ | |

Cesarean section rate | √ | |

Coverage of essential health services | ||

Demand for family planning satisfied through modern methods of contraception | ||

Inputs/processes | ||

Maternal death review coverage | ||

Laws/regulations to guarantee access to sexual and reproductive health care, information, and education | √ | |

Legal frameworks to promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex | √ | |

Protocols/policies on combined care of mother and baby including immediate breastfeeding, | ||

Maternity protection (ILO Convention 183) | ||

International code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes | ||

Costed implementation plan for maternal, newborn, and child health | ||

Midwives are authorized to deliver basic emergency obstetric and newborn care | ||

Legal status of abortion | √ | |

Proportion of women aged 15–49 who make their own informed decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use, and reproductive health care | √ | |

Geographic distribution of facilities that provide basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care (EmOC) | ||

National set of indicators with targets and annual report to inform annual health sector reviews/planning cycles | ||

Percentage of total health expenditure spent on reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health | ||

Out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of total expenditure on health | √ | |

Annual reviews of health spending from all financial sources, including spending on RMNCH | ||

Health worker density and distribution (per 1000 population) | √ | |

Exempt from user fees for [MH-related health] services in the public sector | ||

Availability of functional emergency obstetric care (EmOC) facilities | ||

Density of midwives, by district (by births) | ||

Percentage of facilities that demonstrate readiness to deliver specific services: family planning, antenatal care, basic emergency obstetric care, and newborn care | ||

Civil registration coverage of cause of death (percentage) | √ | |

National policy/strategy to ensure engagement of civil society organization representatives in periodic review of national programs for maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (MNCAH) | √ | |

In the area of newborn health the ENAP has been proposing indicators of impact, coverage, service readiness and policies to measure progress towards improving newborn health and survival and reduction of stillbirths.62 The documentation of stillbirths is still a major measurement issue, also household surveys typically only asks about birth – using so-called “birth histories” questions. Conversely, only “pregnancy histories” allow the documentation of all pregnancies, whether they result into a fetal loss, stillbirth or a live births. Validation work is currently ongoing to establish methods to capture stillbirth better during household surveys and ongoing surveillance.63 The ENAP metrics group proposed a larger number of output and coverage indicators to assess the implementation of evidence-based interventions such as the provision of Kangaroo care for small neonates. In addition, several service readiness indicators are under development based on the idea that key functions and services need to be available in facilities where childbirth care is offered.64

Another key advancement in measurement is the 2018 definition of skilled health personnel (competent health-care professionals) providing care during childbirth (see also above). WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, ICM, ICN, FIGO and IPA used a consultative process involving the global public, academic and other stakeholders and defined competent health-care professionals based on required competences. This new definition emphasizes stronger professional training and education (pre-service training) of the health personnel and focus on the enabling environment as well as standards of practice needed to provide quality intrapartum care.44

Global level monitoring initiatives

The Countdown to 2030 focuses on monitoring in LMIC and provides comprehensive regular updates on progress of maternal, newborn and child health.65 The predecessor, the Countdown to 2015 for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival, was established in 2003 as a supra-institutional movement established to support accountability for improving the health of women and children. Countdown tracks progress and equity in population service coverage. The list of indicators was revised in 2015 with the SDG indicators and many of the indicators put forward by the global initiatives of ENAP and EPMM and others are included in the compilations.66

Data are regularly compiled by WHO, UNICEF, and the World Bank Group and these partners use the same estimates for their institutional data bases (Box 3). In addition, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Seattle, USA, an independent measurement group publishes regularly updated estimates on maternal, newborn and child mortality and cause of death as part of their work on the Global Burden of Disease.67,68 Although global estimates published by the MMEIG, UN IGME and IHME have become very similar in recent years, larger differences for specific countries prevail which complicate country level monitoring of progress. The differences between the estimates are particularly important for maternal mortality estimates. The most important reason for the differences in estimates lie in the general lack of country representative data as CRVS are unavailable in most LMICs. Differences in (i) adjustment procedures, (ii) modeling methods and inclusion of co-variates, and (iii) life tables used to estimate the population to which the models apply are reasons for differences in estimates.20

Box 3 Links to important data repositories

Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health data portal: https://www.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent.

Annual updates of indicators for the SDG and Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health: https://www.who.int/gho/en/.

Annual updates on neonatal mortality along with child mortality: http://childmortality.org/.

Bi-annual updates including 81 high-burden countries and detail global progress achieved and opportunities to expand universal coverage for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health: http://countdown2030.org/.

Annual updates of a large number of indicators relating to child and adolescents health including early childhood development, education and gender equality along maternal and newborn indicators: https://data.unicef.org/.

Annual reports are compiled on indicators of family planning by the Family Planning 2020 collaboration: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/measurement-hub.

Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health policy indicators: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/policy-indicators/en/.

Sexual and reproductive health: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/en/.

Recently, WHO established the Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results (MoNITOR) technical advisory group to provide technical guidance to WHO to ensure harmonized guidance, messages, and tools for maternal and newborn measurement so that countries can collect useful data to track progress toward achieving the SDG.69 This group facilitates the exchange between the measurement initiatives and global level monitoring work as well as on indicator testing and validation to support the SDG agenda. WHO also convenes the Child Health Accountability Tracking technical advisory group with UNICEF and the Global Action for Measurement of Adolescent Health technical advisory group for child and adolescent health, respectively.

Monitoring frameworks, data platforms and resources

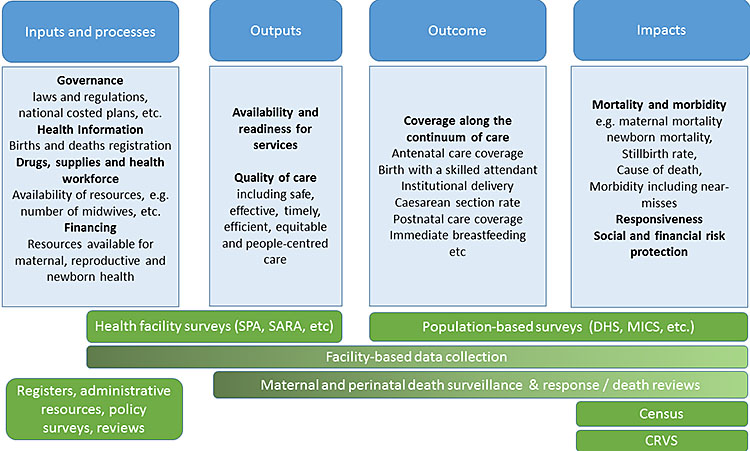

Monitoring is based on the landmark article of Donabedian proposing a framework including input, process and outcome measures for the monitoring of health care delivery.70,71 Frameworks proposed for maternal and child health assessment also broadly follow this same model with assessment of progress along the effect line using input, process, output, outcome, and impact indicators.72,73,74

2

Framework of monitoring of maternal and perinatal health including platforms to generate information adapted from.73,75 SPA, service provision assessment; SARA, service availability and readiness assessment; DHS, demographic and health survey; MICS, multiple indicator cluster survey; CRVS, civil registration and vital statistics.

While impact and outcome indicators are among the best established maternal and perinatal health indicators, monitoring and evaluation today uses a larger number of input, process and output indicators. The new indicators put forward by EPMM II include, for example, a range of policy and other input indicators (Table 1). In addition, service readiness indicators are in the process of being better defined.64 The different indicators demand very diverse platforms for data generation. The input indicators can best be derived from registers (e.g. human resource registers), administrative resources, through policy surveys or by review of country processes and financial reviews. In some countries, health facility surveys are used to establish the availability of human resources or drugs, supplies, etc. Output indicators are typically derived from health facility surveys, but also facility-based data collection is a good source of information. Population-based surveys are the main source for outcome and impact indicators in many LMIC, while CRVS are the preferred source for mortality indicators. Censuses provide information on child mortality – and in some countries also maternal mortality data. In countries where maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems are functioning and have links to community reporting systems, these systems may complement the monitoring and spanning from processes, outputs to cause of deaths. The different systems are explained below in more detail.

Civil registration and vital statistics

A well-functioning CRVS system registers all births and deaths, issues birth and death certificates, and compiles and disseminates vital statistics, including cause of death information.76 Most often births and deaths, and the cause of deaths are certified by a medical professional. Currently, CRVS systems of sufficient quality are found mainly in high-income countries. The latest estimates indicate that globally only 38% of all deaths and 65% of births of children aged under 5 years are being registered.77 However, even in countries with good quality births and deaths registration, estimates are often not complete. Particular indirect, associated, and late maternal deaths are often misclassified.22,23,24 In some countries, such as the United States of America, a tick box on the death certificate explicitly asks if the death could be pregnancy-related to act as a reminder. This check-question on the death certificate improved the ascertainment of all maternal deaths considerably78 and WHO recommends its use on deaths certificates. However, in most LMIC CRVS systems are either not yet established or incomplete, although major investments are under way. To note, CRVS systems provide estimates on mortality rates as well as cause of deaths.

HDSS use the principle of civil registrations and vital statistics for a limited population. A typical HDSS encompasses less than 100,000 people, thus estimates are not representative of a country. In India and a few other countries, national-representative HDSS have been employed. The sample registration system in India, for example, has been developed in the 1960s and provides information on the burden of disease across India.79,80 In Tanzania a similar principle has been employed in a sample of districts, operating from 2014 to 2017.81 Most health and demographic surveillance sites (HDSS) include verbal autopsies in their data collection and can thus establish cause of death estimates. The main advantage of HDSS estimates is thus that a cause of death is available, however, estimates are not representative of a country unless the principle of sample registration is used with data collection from several locations.

Censuses

Censuses, originally only used to establish population counts, are now used to establish mortality estimates. During censuses the head of household is asked if any death occurred in the household and the age and sex of the deceased is recorded. If any deaths in women of reproductive age is reported, questions are asked to determine the potential relationship with pregnancy, childbirth or the 6 weeks thereafter.19 The interviews typically do not include a verbal autopsies questionnaire to investigate into the cause of deaths, why only pregnancy-related but not maternal mortality care be estimated from censuses.19

Population-based surveys

The best-known population-based surveys are the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). DHS are national representative household surveys that assess fertility, maternal and child health as well as nutrition, mortality, and demographic characteristics. The DHS developed out of the World Fertility Surveys which were conducted 1974–1983. DHS use standardized questionnaires which are administered to the heads of household and female members of households of reproductive age (15–49 years). The surveys use cluster-sampling and are typically representative of the country, except if parts of the country cannot be surveyed in case of unrest or war.

Data are typically collected at 3–5 year intervals, but in some countries smaller surveys are done in between. More than 300 surveys in over 90 countries have been carried out. DHS reports and data are available from the DHS homepage (https://dhsprogram.com/). Also, data can be obtained for secondary data analysis and numerous numbers of papers have been published using these data.

A similar type of household survey has been supported by UNICEF since the mid-1990s, the MICS. MICS are typically undertaken in countries where no DHS has been done. While there is overlap in questions posed at the household level and the indicators derived, differences prevail. The reports are available from UNICEF http://mics.unicef.org/. In addition to these two survey types Reproductive Health Surveys have been conducted since 1985 with technical support from the Center of Disease Control (USA). These surveys have evolved out of the Contraceptive Prevalence Surveys performed in the 1970s. These surveys were expanded to include maternal and child health concerns in the early 1980s. A few dozens of such surveys have been conducted primarily in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa and Eastern Europe http://ghdx.healthdata.org/series/reproductive-health-survey-rhs and the Arabic countries http://ghdx.healthdata.org/organizations/pan-arab-project-family-health-papfam.

Maternal and perinatal deaths surveillance and response/deaths reviews

Reviewing clinical case notes of a deceased mother or infant and establishing the causes of death as well as the underlying community- and health service-related factors has long been recommended to improve the quality of care and to reduce perinatal mortality.82 Recently, this method has been also recommended as a surveillance tool by WHO, although the ability to establish mortality rates for a defined population depends on the ability to also incorporate community deaths.

Reproductive Age Mortality Studies (RAMOS)

RAMOS are a special type of data collection where several sources, including facility-based data are used. Sources include interviews of family members, health facility records, burial records, and community health workers reports. Health facility information or verbal autopsies are then typically used to determine a cause of death.8 However, this method is not without shortcomings. First, the quality depends on the efforts and methods to record all deaths. Second, estimates on the number of live births can be difficult to obtain from the same period and geographical area.

Facility-based data collection

Facility-based data collection is a cornerstone of national monitoring. Such systems are often called Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) and in large parts of Africa and Asia, data collection is supported by the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS-2), using a web-based open-source information system for the data entry at district level http://www.hisp.org/services/dhis-2/. However, data compilation in facilities is mostly still paper-based and aggregated so-called summary sheets are transferred to the district level. Facility-based data may also include laboratory information system or medicine information system or any electronic medical records. In many high-income countries perinatal registers are established,83 but only few data are available from data repositories http://ghdx.healthdata.org/search/site/perinatal%20registers. In many countries specialized data collections have been introduced to facilitate surveillance and auditing of maternal and perinatal deaths84 (see above on maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response). The most known system is that of the United Kingdom where the national inquiry into maternal deaths has been running for over 60 years.85

Facility-based data can provide important information on services and interventions provided to mothers and infants, who seek care in facilities. The drawback of using facility data is, however, that the statistics miss home births and deaths. It is also difficult to know the exact target group of the services to derive a denominator. In response “expected births” or “expected population” based on census data and national birth rates are calculated for catchment areas. Although the use of this denominator may be useful in some settings, the appropriate computation of coverage indicators is often complicated by care seeking at higher level facilities or in other facilities than in the catchment areas or districts. It is important to note that such “catchment areas” need to be large enough so that mortality rates or ratios can be calculated. Another constraint of facility-based data is often the quality of data. In particular deaths estimates are typically too low, while estimates of some coverage data such as vaccination or facility delivery have been shown to be acceptable in some countries.86,87

Health facility surveys

The best known health facility surveys (HFA) are the Service Availability and Readiness Assessments (SARA) by WHO https://www.who.int/healthinfo/publications_topic_data_collection/en/ and the Service Provision Assessments (SPA) of the DHS program https://www.dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm. Both surveys aim to document the available services and inputs in facilities. They assess for example infrastructure, human resources and availability of key resources such as water, electricity, infection prevention measures, etc. They might also more specifically include vaccinations, medicines and other supplies. These facility surveys complement the household surveys and are often performed at 2–5 year intervals. In some countries all facilities are surveyed (facility censuses), in others only a sample of facilities.

Other surveys and data collection platforms

To assess policies and national regulations WHO and partners are undertaking policy surveys at regular intervals asking countries to report on national regulations and laws (see https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/policy-indicators/en/). In addition, national administrative resources such as registers of all certified health providers or of all health facilities sometimes including their geographical positioning are used for documentation.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Measuring maternal and perinatal health, and progress towards the SDGs needs a variety of measurements and data sources.

- Indicators span from policy and input, to facility readiness, coverage and impact indicators.

- Data platforms include policy surveys, facility registers or facility surveys and population-based surveys and census.

- Each of the measurements and data sources have their own advantages, disadvantages and limitations which are important considerations when reviewing progress for maternal and perinatal health.

- Maternal mortality is one of the oldest indicators, but measurement problems prevail as quality registration of all births and deaths is still insufficiently developed in most LMIC.

- Estimates are compiled at regular intervals to ensure accountability and progress towards reaching the aspirational SDGs.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Högberg U, Wall S. Secular trends in maternal mortality in Sweden from 1750 to 1980. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1986;64(1):79–84. | |

Loudon I. Death in Childbirth. An international study of maternal care and maternal mortality 1800–1950. Oxford: Clarendon Press Oxford, 1992. | |

Macfarlane A, Mugford M. Birth counts: statistics of pregnancy and childbirth. 2nd edn. London: The Stationery Office, 2000:Vol. 1. | |

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Maternal mortality in 1995: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2001:56. | |

WHO. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Geneva: WHO, 1994. | |

WHO. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM. WHO: Geneva, 2012. | |

World Health Organization, et al. Maternal mortality 2000 to 2017. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, 2019 [cited 2019 December]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327596. | |

WHO, et al. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990–2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. WHO: Geneva, 2015. | |

World Health Organization. Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators. 2018 [cited 2019 16 Nov]; Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/indicators/2018/en/. | |

Mahler H. The safe motherhood initiative: a call to action. Lancet 1987;1(8534):668–70. | |

AbouZahr C, Royston E. Maternal Mortality: A Global Factbook. Genève: WHO, 1991. | |

WHO, et al. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and The World Bank. WHO: Geneva, 2010. | |

WHO, et al. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates. Geneva: 2012. | |

Graham W, Brass W, Snow R. Estimating maternal mortality: The sisterhood method. Studies in Family Planning 1989;20(3):125–35. | |

WHO, UNICEF. The Sisterhood Method for Estimating Maternal Mortality: Guidance notes for potential users. Geneva: Division of Reproductive Health, WHO, 1997. | |

The DHS Program. The DHS Program. Demographic and Health Surveys [cited 2018 1st July]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/. | |

Graham W, et al. Measuring maternal mortality: An overview of opportunities and options for developing countries. BMC Medicine 2008;6(1):12. | |

National Bureau Of Statistics (NBS) Ministry of Finance and Office of Chief Government Statistician. Ministry of State; President Office; State House and Good Governance. Mortality and Health. Dar-es-Salaam: Tanzania, 2015. | |

Stanton C, et al. Every death counts: measurement of maternal mortality via the census. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 2001;79(7):657–64. | |

AbouZahr C. New estimates of maternal mortality and how to interpret them: choice or confusion? Reproductive Health Matters 2011;19(37):117–28. | |

AbouZahr C, Gollogly L, Stevens G. Better data needed: everyone agrees, but no one wants to pay. The Lancet 2010;375(9715):619–21. | |

Gissler M, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths in four regions of Europe and the United States in 1999–2000: Characterisation of unreported deaths. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2007;133(2):179–85. | |

Horon IL, Cheng D. Underreporting of pregnancy-associated deaths. Am J Public Health 2005;95(11):1879-. | |

Horon IL. Underreporting of Maternal Deaths on Death Certificates and the Magnitude of the Problem of Maternal Mortality. Am J Public Health 2005;95(3):478–82. | |

INDEPTH Network. Better Health Information for Better Health Policy. [cited 2018 15 December]; Available from: http://www.indepth-network.org/. | |

Streatfield PK, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in Africa and Asia: evidence from INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance System sites. Global Health Action 2014;7(1):25368. | |

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015 [cited 2019 19 April]; Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs. | |

World Health Organization. Perinatal mortality. A listing of available information (WHO/FRH/MSM/96.7). 1996; Available from: https://www.popline.org/node/312042. | |

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? The Lancet 2005;365(9462):891–900. | |

Stanton C, et al. Stillbirth rates: delivering estimates in 190 countries. The Lancet 2006;367(9521):1487–94. | |

UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality. Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, 2019. | |

UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey MICS4. [cited 2019 1st July]; Available from: http://www.childinfo.org/mics4_questionnaire.html. | |

Haws RA, et al. “These are not good things for other people to know”: How rural Tanzanian women’s experiences of pregnancy loss and early neonatal death may impact survey data quality. Social Science & Medicine 2010;71(10):1764–72. | |

Blencowe H, et al. Measuring maternal, foetal and neonatal mortality: Challenges and solutions. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2016;36:14–29. | |

United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Millennium Declaration. A/RES/55/2 2000 [cited 2019 Sept]; Available from: http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm. | |

United Nations and International Conference on Population and Decelopment (ICPD). The Final Programme of Action agreed to in Cairo. 1994 [cited 2018 6 December]; Available from: http://enb.iisd.org/cairo.html. | |

United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. The Fourth World Conference on Women. 1995 [cited 2018 16 July]; Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf. | |

Liljestrand J. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality worldwide. Current opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;12:513–517. | |

World Health Organization. Every Pregnancy Faces Risk. 7 April 1998; Available from: http://www.who.int/docstore/world-health-day/en/pages1998/whd98_05.html. | |

WHO. Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant. A joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. 2004 [cited 2019 16 June ]; Available from: http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/9241591692/en/index.html. | |

Montagu D, et al. Where women go to deliver: understanding the changing landscape of childbirth in Africa and Asia. Health Policy Plan 2017. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx060. [Epub ahead of print]. | |

National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi], ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. NSO and ICF: Zomba, Malawi, and Rockville, Maryland, USA, 2019. | |

Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India's Conditional Cash Transfer Programme (the JSY) to Promote Institutional Birth: Is There an Association between Institutional Birth Proportion and Maternal Mortality? PLoS One, 2013;8(6):e67452. | |

WHO, et al. Definition of skilled health personnel providing care during childbirth. The 2018 joint statement by WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, ICM, ICN, FIGO, IPA. 2018; Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/statement-competent-mnh-professionals/en/. | |

Cleland J, et al. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet 2006;368(9549):1810–27. | |

Horton R, Peterson HB. The rebirth of family planning. The Lancet 2012;380(9837):77. | |

FamilyPlanning2020. Data Hub Increasing the Availability, Visability and Use of Family Planning Data. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/measurement-hub#what-we-measure. | |

Maine D, et al. Guidelines for Monitoring the Availability and Use of Obstetric Services. New York: UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA, 1997. | |

WHO, et al. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: WHO, 2009. | |

AMDD. Program note: using the UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Morocco, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2003;80:222–30. | |

AMDD. Program note. Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Niger, Rwanda and Tanzania. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2003;83(1):112–20. | |

WHO, UNICEF. Countdown to 2015 Decade Report (2000–2010). Taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival. WHO & UNICEF: Geneva, 2010. | |

Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AMDD). EmOC toolkit. [cited 2018 July]; Available from: https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/research/averting-maternal-death-and-disability-amdd/toolkit. | |

Allen SM, Opondo C, Campbell OMR. Measuring facility capability to provide routine and emergency childbirth care to mothers and newborns: An appeal to adjust for delivery caseload of facilities. PLOS ONE 2017;12(10):e0186515. | |

Every Woman Every Child. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health 2016–2030. 2015 [cited 2017 21 October]; Available from: http://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org/. | |

Every Newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2014. | |

Strategies towards ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). World Health Organization: Geneva, 2015. | |

Global Financing Facility in support of Every Woman Every Child (GFF). 2016 [cited 2017 21 October]; Available from: http://globalfinancingfacility.org/. | |

Moller A-B, et al. Measures matter: A scoping review of maternal and newborn indicators. PLOS ONE 2018;13(10):e0204763. | |

WHO and Human reproduction programme (hrp). Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). 2015 [cited 2018 10 Feb]; Available from: http://who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/maternal_perinatal/epmm/en/. | |

Jolivet RR, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2018;18(1):258. | |

Healthy Newborn Network. ENAP metrics. 2018; Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/issues/global-initiatives/enap-metrics/. | |

Kadobera D, et al. Comparing performance of methods used to identify pregnant women, pregnancy outcomes, and child mortality in the Iganga-Mayuge Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, Uganda. Global Health Action 2017;10(1):1356641. | |

Moxon SG, et al. Service readiness for inpatient care of small and sick newborns: what do we need and what can we measure now? Journal of Global Health 2018;8(1):010702. | |

Requejo J, Victora CG, Bryce J. A Decade of Tracking Progress for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival. The 2015 Report. 2015 [cited Aug 2016; Available from: http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/reports-and-articles/2015-final-report. | |

Countdown to 2013 Women's, C.s.a.A.H. Countdown Reports and Publications. [cited 2018 6 December]; Available from: http://countdown2030.org/reports-and-publications. | |

Kassebaum NJ, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2013;2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 2016;388(10053):1775–812. | |

Wang H, et al. Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 2017;390(10100):1084–150. | |

Moran AC, et al. ‘What gets measured gets managed’: revisiting the indicators for maternal and newborn health programmes. Reproductive Health 2018;15(1):19. | |

Donabedian A. The Quality of Care. JAMA 1988;260(12):1743–8. | |

Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press, 1980. | |

Bryce J, et al. Evaluating the scale-up for maternal and child survival: A common framework. 2010 [cited 2011 October]; Available from: http://www.jhsph.edu/bin/a/d/common_evaluation_framework.pdf. | |

Bryce J, et al. Evaluating the scale-up for maternal and child survival: a common framework. International Health 2011;3(3):139–46. | |

Diaz T, et al. Framework and strategy for integrated monitoring and evaluation of child health programmes for responsive programming, accountability, and impact. BMJ 2018;362:k2785. | |

Monitoring und Evaluation group of IHP+. Monitoring, Evaluation and review og National Health Strategies. A country-led platform for information and accountability. 2011 [cited 2019 19 April]; Available from: http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Tools/M_E_Framework/M%26E.framework.2011.pdf. | |

World Health Organization. Civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS). Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/civil_registration/en/. | |

Mikkelsen L, et al. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. The Lancet 2015;386(10001):1395–406. | |

MacDorman M, et al. Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends From Measurement Issues. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;128(3):447–55. | |

Dandona L, et al. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 2017;390(10111):2437–60. | |

Office of Registrar General, I. Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2014–16. Sample Registration System 2016 [cited 2018 20 Dec]; Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/MMR%20Bulletin-2014–16.pdf. | |

Kabadi GS, et al. Data Resource Profile: The sentinel panel of districts: Tanzania’s national platform for health impact evaluation. International Journal of Epidemiology 2015;44(1):79–86. | |

AbouZahr C, et al. Beyond the numbers. Reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Geneva, 2004. | |

Zeitlin J, Mohangoo A, Delnord M. European Perinatal Health Report. Health and Care of Pregnant Women and Babies in Europe in 2010. 2011; Available from: http://www.europeristat.com/images/doc/EPHR2010_w_disclaimer.pdf. | |

WHO, et al. Maternal death surveillance and response. Technical guidance. Information for action to prevent maternal death. 2013; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/87340/1/9789241506083_eng.pdf?ua=1. | |

Knight M, Tuffnell D. A View From the UK: The UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2018;61(2):347–58. | |

Amouzou A, et al. Monitoring child survival in ‘real time’ using routine health facility records: results from Malawi. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2013;18(10):1231–9. | |

Maina I, et al. Using health-facility data to assess subnational coverage of maternal and child health indicators, Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2017;95(10):683–94. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)