Anatomy Atlas

Vulva

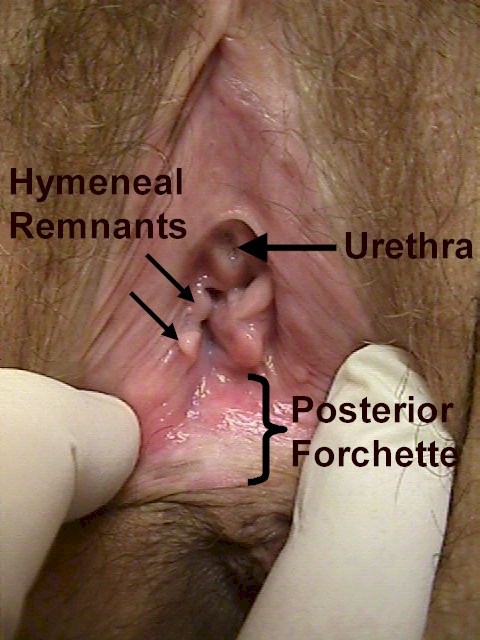

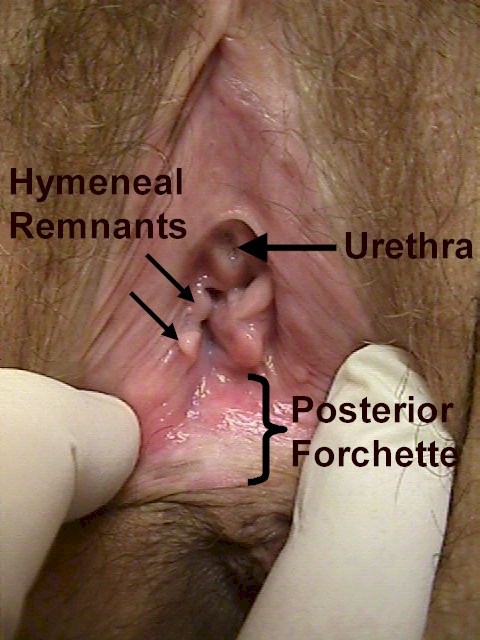

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Normal Anatomy of a 30-year-old multipara. (Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All rights reserved.)

Fig. 7.External genitalia. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Fig. 7.External genitalia. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Fig. 8.Deep perineal structures, pudendal artery, and genital tract blood vessels. Abbreviations: BC, bulbocavernosus muscle; CC, crus of the clitoris; ES, external anal sphincter; IC, ischiocavernosus muscle; SM, superficial transverse perineal muscle; VB, vestibular bulb. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Fig. 8.Deep perineal structures, pudendal artery, and genital tract blood vessels. Abbreviations: BC, bulbocavernosus muscle; CC, crus of the clitoris; ES, external anal sphincter; IC, ischiocavernosus muscle; SM, superficial transverse perineal muscle; VB, vestibular bulb. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Back to Top

Pelvis

View of the pelvic inlet and pelvic muscles from above. Abbreviations used in Figures 1 through 4: AS, alae of sacrum; ATFP, arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis; ATLA, arcus tendineus levator ani; C, coccyx; CM, coccygeus muscle; EAS, external anal sphincter; GSF, greater sciatic foramen; IC, iliac crest; IlCM, iliococcygeus muscle; IPR, inferior (ischio- )pubic ramus; IS, ischial spine; IT, ischial tuberosity; LSF, lesser sciatic foramen; LT, linea terminalis; OF, obturator foramen; OIM, obturator internus muscle; PCM, pubococcygeus muscle; PM, piriformis muscle; PS, pubic symphysis; S, sacrum; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SP, sacral promontory; SPR, superior (ischio- ) pubic ramus; SSL, sacrospinous ligament; STL, sacrotuberous ligament; UGH, urogenital hiatus.

View of the pelvic inlet and pelvic muscles from above. Abbreviations used in Figures 1 through 4: AS, alae of sacrum; ATFP, arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis; ATLA, arcus tendineus levator ani; C, coccyx; CM, coccygeus muscle; EAS, external anal sphincter; GSF, greater sciatic foramen; IC, iliac crest; IlCM, iliococcygeus muscle; IPR, inferior (ischio- )pubic ramus; IS, ischial spine; IT, ischial tuberosity; LSF, lesser sciatic foramen; LT, linea terminalis; OF, obturator foramen; OIM, obturator internus muscle; PCM, pubococcygeus muscle; PM, piriformis muscle; PS, pubic symphysis; S, sacrum; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SP, sacral promontory; SPR, superior (ischio- ) pubic ramus; SSL, sacrospinous ligament; STL, sacrotuberous ligament; UGH, urogenital hiatus.

Sagittal section of the pelvic bones.

Sagittal section of the pelvic bones.

View of the pelvic outlet and pelvic muscles from below.

View of the pelvic outlet and pelvic muscles from below.

Pelvis with pelvic wall muscles and pelvic diaphragm shown.

Pelvis with pelvic wall muscles and pelvic diaphragm shown.

Frontal section showing uterus and pelvic floor. © 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All

rights reserved.)

Frontal section showing uterus and pelvic floor. © 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All

rights reserved.)

Back to Top

Pelvic Support

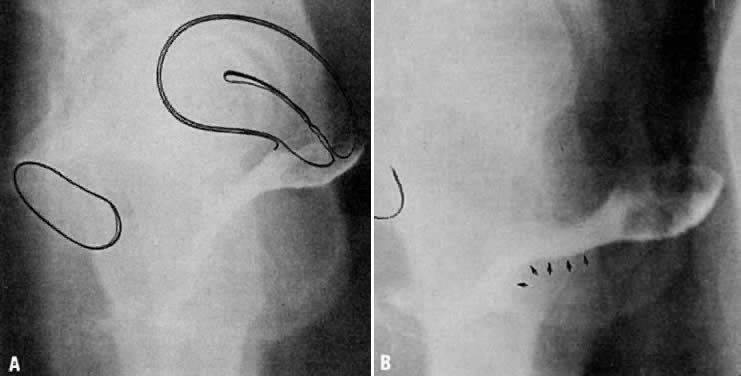

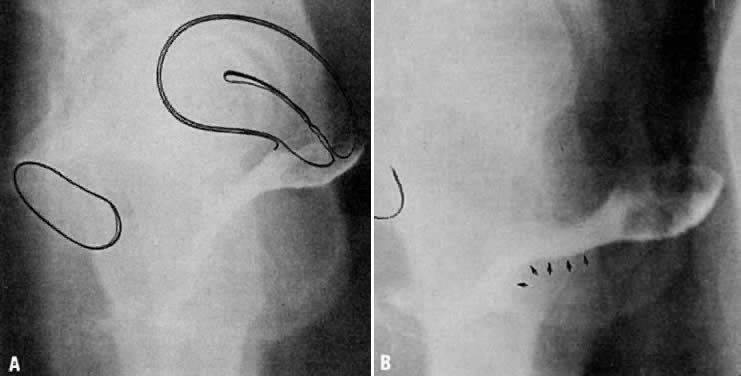

A and B. Normal vaginal depth and axis. Colpogram of healthy 25-year-old nulligravida. The vaginal walls are painted with barium paste. The patient is standing at rest (A). The position of the symphysis is outlined to the left. The effect of straining by a Valsalva maneuver is shown (B). The perineal curve of the lower vagina is unchanged, but the horizontal axis of the upper vagina is accentuated with straining.(Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL: Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol 36:251, 1970)

A and B. Normal vaginal depth and axis. Colpogram of healthy 25-year-old nulligravida. The vaginal walls are painted with barium paste. The patient is standing at rest (A). The position of the symphysis is outlined to the left. The effect of straining by a Valsalva maneuver is shown (B). The perineal curve of the lower vagina is unchanged, but the horizontal axis of the upper vagina is accentuated with straining.(Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL: Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol 36:251, 1970)

The vaginal axis of the living human female. Notice the almost horizontal upper vagina and rectum lying on and parallel to the levator plate. The latter is formed by fusion of the pubococcygeal muscles (A) posterior to the rectum. The anterior limit of the point of fusion is the margin of the genital hiatus, immediately posterior to the rectum.

The vaginal axis of the living human female. Notice the almost horizontal upper vagina and rectum lying on and parallel to the levator plate. The latter is formed by fusion of the pubococcygeal muscles (A) posterior to the rectum. The anterior limit of the point of fusion is the margin of the genital hiatus, immediately posterior to the rectum.

Sagittal section shows the relationship between the rectovaginal septum (RVS) as it blends with the superior border of the perineal body (PB). (Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 42. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Sagittal section shows the relationship between the rectovaginal septum (RVS) as it blends with the superior border of the perineal body (PB). (Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 42. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Drawing showing the normal relationship between the vagina and the arcus tendinei. The arcus tendinei run from the back of the pubis to the ischial spine on each side of the pelvis.(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 18. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Drawing showing the normal relationship between the vagina and the arcus tendinei. The arcus tendinei run from the back of the pubis to the ischial spine on each side of the pelvis.(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 18. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Fortuitous section through the urethra (left) and vagina (below) shows some of their distinct fibromuscular support. The ventral support of the anterior sulcus by its attachments to the arcus tendineus and cardinal ligament are shown on the right.(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 19. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Fortuitous section through the urethra (left) and vagina (below) shows some of their distinct fibromuscular support. The ventral support of the anterior sulcus by its attachments to the arcus tendineus and cardinal ligament are shown on the right.(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 19. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

The urethra is both suspended ( central arrows show the attachments and pull of the pubourethral “ligament” portions of the urogenital diaphragm) and supported ( lateral arrows indicate the attachments of the vagina by intermediate connective tissue to the arcus tendineus).(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 21. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

The urethra is both suspended ( central arrows show the attachments and pull of the pubourethral “ligament” portions of the urogenital diaphragm) and supported ( lateral arrows indicate the attachments of the vagina by intermediate connective tissue to the arcus tendineus).(Nichols DH, Randall CL: Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 21. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, with permission)

Cross section of female pelvis through lower midportion of vagina. Note the convex configuration of the pubococygeus (PC). The rectovaginal space (RVS), as well as the position of the rectovaginal septum (RVSe), is indicated between the rectum and vagina. The blood vessels (bv) in connective tissue lateral to the vagina are shown. These tend to give the vagina its H-shape configuration. The fibers of Luschka (FL) are shown as they attach the paravaginal connective tissue to the sheath of the pubococcygeus.

Cross section of female pelvis through lower midportion of vagina. Note the convex configuration of the pubococygeus (PC). The rectovaginal space (RVS), as well as the position of the rectovaginal septum (RVSe), is indicated between the rectum and vagina. The blood vessels (bv) in connective tissue lateral to the vagina are shown. These tend to give the vagina its H-shape configuration. The fibers of Luschka (FL) are shown as they attach the paravaginal connective tissue to the sheath of the pubococcygeus.

The effect of traction on the connective tissue fibers of the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Traction applied by forceps placed in the center of a piece of plastic net demonstrates the distortion of the pelvic tissues resulting from traction on the cervix. Condensation and obliteration of interareolar

spaces account for ligaments apparent at operation, reinforced by

blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves and their sheaths, which both

enter and exit along the lateral margin of the upper vagina and

cervix.(Adapted from Range RL, Woodburne

RT: The gross and microscopic anatomy of the transverse cervical

ligament. Am J Obstet Gynecol 90:460, 1964)

The effect of traction on the connective tissue fibers of the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Traction applied by forceps placed in the center of a piece of plastic net demonstrates the distortion of the pelvic tissues resulting from traction on the cervix. Condensation and obliteration of interareolar

spaces account for ligaments apparent at operation, reinforced by

blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves and their sheaths, which both

enter and exit along the lateral margin of the upper vagina and

cervix.(Adapted from Range RL, Woodburne

RT: The gross and microscopic anatomy of the transverse cervical

ligament. Am J Obstet Gynecol 90:460, 1964)

The cardinal ligament is shown as it

attaches to the lateral portions of both cervix and upper third

of the vagina. Notice that it follows the angulation of the intersecting

axes of these two organs.

The cardinal ligament is shown as it

attaches to the lateral portions of both cervix and upper third

of the vagina. Notice that it follows the angulation of the intersecting

axes of these two organs.

A. Connective tissue planes and

spaces of the female pelvis. Frontal section through female pelvis

near upper third of vagina. The paravesical (PVS) is shown

lateral to the bladder (Blad.). The vesicovaginal space (VVS)

is seen between the bladder and vagina, and the rectovaginal space

(RVS) is shown between the vagina and the rectum. The paired

pararectal spaces (PRS) are seen lateral to the rectum. Note

that the ischial spines (IS) are found in the lateral wall

of the pararectal spaces. The cardinal ligaments of the vagina (horizontal

connective tissue ground bundle) are shown extending from the sides

of the vagina to the pelvic wall. The tissue fuses laterally to

the connective tissue capsule of the levator ani (LA), which

itself takes origin from the fascia of the obturator internus muscle

along a white line identified as the arcus tendineous (AT).

The rectovaginal septum (RVSe) is noted between the vagina

and the rectovaginal space. The ureters (U) can be seen in

the tissue between the paravesical space and the vesicovaginal space.

Note the retrorectal space (RRS). B. Diagrammatic

cross section of the female pelvis through the cervix. The prevesical

space (PrVS) is seen anterior to the bladder. It is separated

from the paravesical space (PaVS) by the ascending bladder

septum (ABSe). The latter also separates the paravesical

space from the vesicocervical space (VCS). The descending

rectal septum (DRS) separates the retrorectal space (RRS)

from the pararectal space (PaRS). Note the posterior cul-de-sac

(CD) and cardinal ligament (CL). (Adapted

from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. LK Ferguson (trans):

Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

A. Connective tissue planes and

spaces of the female pelvis. Frontal section through female pelvis

near upper third of vagina. The paravesical (PVS) is shown

lateral to the bladder (Blad.). The vesicovaginal space (VVS)

is seen between the bladder and vagina, and the rectovaginal space

(RVS) is shown between the vagina and the rectum. The paired

pararectal spaces (PRS) are seen lateral to the rectum. Note

that the ischial spines (IS) are found in the lateral wall

of the pararectal spaces. The cardinal ligaments of the vagina (horizontal

connective tissue ground bundle) are shown extending from the sides

of the vagina to the pelvic wall. The tissue fuses laterally to

the connective tissue capsule of the levator ani (LA), which

itself takes origin from the fascia of the obturator internus muscle

along a white line identified as the arcus tendineous (AT).

The rectovaginal septum (RVSe) is noted between the vagina

and the rectovaginal space. The ureters (U) can be seen in

the tissue between the paravesical space and the vesicovaginal space.

Note the retrorectal space (RRS). B. Diagrammatic

cross section of the female pelvis through the cervix. The prevesical

space (PrVS) is seen anterior to the bladder. It is separated

from the paravesical space (PaVS) by the ascending bladder

septum (ABSe). The latter also separates the paravesical

space from the vesicocervical space (VCS). The descending

rectal septum (DRS) separates the retrorectal space (RRS)

from the pararectal space (PaRS). Note the posterior cul-de-sac

(CD) and cardinal ligament (CL). (Adapted

from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. LK Ferguson (trans):

Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

Stereograph showing the connective tissue

septa and paravaginal spaces in relation to the bladder, uterus,

and rectum. The spaces permit these three organs to function independently

of one another.(Nichols, DH, Randall CL:

Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 42. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins,

1989, with permission)

Stereograph showing the connective tissue

septa and paravaginal spaces in relation to the bladder, uterus,

and rectum. The spaces permit these three organs to function independently

of one another.(Nichols, DH, Randall CL:

Vaginal Surgery, 3rd ed, p 42. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins,

1989, with permission)

Median sagittal section through the

female pelvis showing the midline connective tissue spaces between

bladder, vagina, and rectum. The vesicocervical space (VCS)

is separated from the vesicovaginal space (VVS) by fusion

between the adventitia of the cervix and bladder, called the supravaginal

septum (SVSe). The rectovaginal space (RVS) is shown between

the rectum and the vagina, extending from the perineal body to the

bottom of the cul-de-sac of Douglas. The rectovaginal septum is

a condensation of tissue attached to the posterior vaginal wall

along the full length of the rectovaginal space.

Median sagittal section through the

female pelvis showing the midline connective tissue spaces between

bladder, vagina, and rectum. The vesicocervical space (VCS)

is separated from the vesicovaginal space (VVS) by fusion

between the adventitia of the cervix and bladder, called the supravaginal

septum (SVSe). The rectovaginal space (RVS) is shown between

the rectum and the vagina, extending from the perineal body to the

bottom of the cul-de-sac of Douglas. The rectovaginal septum is

a condensation of tissue attached to the posterior vaginal wall

along the full length of the rectovaginal space.

Direction of the pelvic axis in the erect posture.(Porges RF, Porges JC, Blinick G: Mechanisms of uterine support and the

pathogenesis of uterine prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 15:711, 1960)

Direction of the pelvic axis in the erect posture.(Porges RF, Porges JC, Blinick G: Mechanisms of uterine support and the

pathogenesis of uterine prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 15:711, 1960)

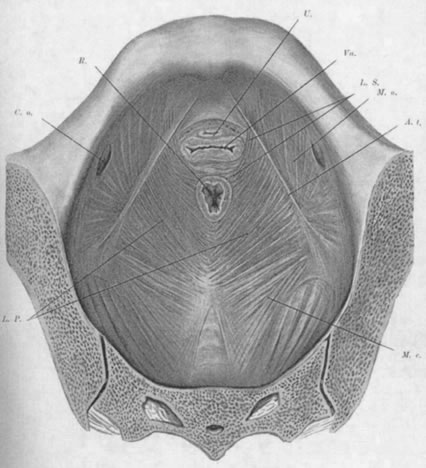

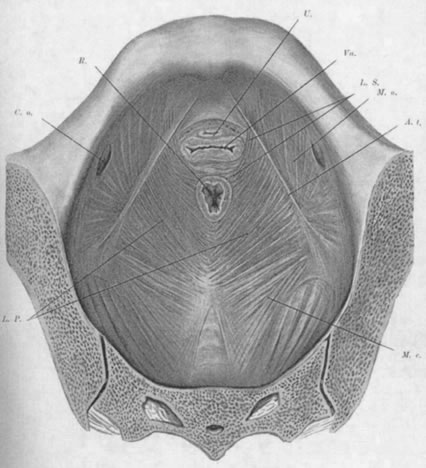

Pelvic floor, seen from above.(Halban J, Tandler J: Anatomie und Aetiologie des Genital-prolapse beim

Weibe. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907; translated, Porges RF, Porges

JC: Obstet Gynecol 15:790, 1960)

Pelvic floor, seen from above.(Halban J, Tandler J: Anatomie und Aetiologie des Genital-prolapse beim

Weibe. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907; translated, Porges RF, Porges

JC: Obstet Gynecol 15:790, 1960)

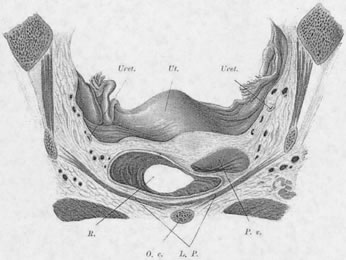

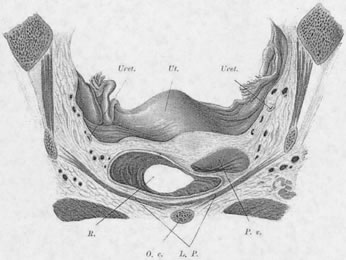

Coronal section.(Halban J, Tandler J: Anatomie und Aetiologie des Genital-prolapse beim

Weibe. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907; translated, Porges RF, Porges

JC: Obstet Gynecol 15:790, 1960)

Coronal section.(Halban J, Tandler J: Anatomie und Aetiologie des Genital-prolapse beim

Weibe. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907; translated, Porges RF, Porges

JC: Obstet Gynecol 15:790, 1960)

Back to Top

Uterus, Fallopian Tubes and Ovaries

Uterus and adnexal structures. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with

permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations

by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Uterus and adnexal structures. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with

permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations

by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Schema of the internal organs of generation.

Schema of the internal organs of generation.

Dissection showing the cephalic aspect of the female genitalia and their

relationships.

Dissection showing the cephalic aspect of the female genitalia and their

relationships.

Transverse section of the abdomen above the crests of the ilia. This section

is 1 inch above the pubis and extends through the disk between the

sacrum and the last lumbar vertebra.

Transverse section of the abdomen above the crests of the ilia. This section

is 1 inch above the pubis and extends through the disk between the

sacrum and the last lumbar vertebra.

Arterial blood supply of the normal tube, ovary, and uterus. (Courtesy

of Dr John A. Sampson.) (From Norris: Gonorrhoea in Women. Philadelphia: Saunders.)

Arterial blood supply of the normal tube, ovary, and uterus. (Courtesy

of Dr John A. Sampson.) (From Norris: Gonorrhoea in Women. Philadelphia: Saunders.)

Ventral view of a deep dissection of the urinary bladder and the blood

supply to the left side of the internal genitalia, showing the relation

of the uterine vessels to the ureter.

Ventral view of a deep dissection of the urinary bladder and the blood

supply to the left side of the internal genitalia, showing the relation

of the uterine vessels to the ureter.

Blood supply of the internal organs of generation with relation to the

ureter and trigone of the urinary bladder.

Blood supply of the internal organs of generation with relation to the

ureter and trigone of the urinary bladder.

Uterine anomalies. A. Uterus duplex unicollis. B. Uterus duplex with double vagina. C. Uterus didelphys. D. Uterus septus with single vagina. E. Uterus subseptus. F. Uterus arcuatus. G. Uterus unicornis with rudimentary contralateral hemiuterus.

Uterine anomalies. A. Uterus duplex unicollis. B. Uterus duplex with double vagina. C. Uterus didelphys. D. Uterus septus with single vagina. E. Uterus subseptus. F. Uterus arcuatus. G. Uterus unicornis with rudimentary contralateral hemiuterus.

Mesonephric vestiges. (After Cullen.)

Mesonephric vestiges. (After Cullen.)

A. Mullerian and wolffian ducts.

B. Fusion of müllerian ducts. C. Regression of

mesonephric ducts. D. Uterus, cervix, and vagina.

A. Mullerian and wolffian ducts.

B. Fusion of müllerian ducts. C. Regression of

mesonephric ducts. D. Uterus, cervix, and vagina.

Diagram of various lesions causing hydrometrocolpos. A. Imperforate hymen. B. Transverse septum. C and D. Low and high atresia of vagina. (From Spencer R, Levy DM: Hydrometrocolpos: Report of three cases and review

of the literature. Ann Surg 155:558, 1962.)

Diagram of various lesions causing hydrometrocolpos. A. Imperforate hymen. B. Transverse septum. C and D. Low and high atresia of vagina. (From Spencer R, Levy DM: Hydrometrocolpos: Report of three cases and review

of the literature. Ann Surg 155:558, 1962.)

Development of the lower uterine segment. The cross-hatched area represents

the myometrium. (Llewellyn-Jones D: Fundamentals of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd ed. London, Farber & Farber, 1977. Based on observations of C.P. Wendell-Smith. Used

with permission.)

Development of the lower uterine segment. The cross-hatched area represents

the myometrium. (Llewellyn-Jones D: Fundamentals of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd ed. London, Farber & Farber, 1977. Based on observations of C.P. Wendell-Smith. Used

with permission.)

Back to Top

Anorectal Canal

Anatomy of anal canal.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physiology. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 5, 2nd ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Anatomy of anal canal.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physiology. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 5, 2nd ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Relationship of external and internal sphincter, coronal view.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physio-logy. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 6, 2nd ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Relationship of external and internal sphincter, coronal view.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physio-logy. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 6, 2nd ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Relationship of perirectal fascia in women.(Godlewski G, Prudhomme M: Embryology and anatomy of the anorectum. Surg

Clin North Am 80(1):319, 2000.)

Relationship of perirectal fascia in women.(Godlewski G, Prudhomme M: Embryology and anatomy of the anorectum. Surg

Clin North Am 80(1):319, 2000.)

Anatomy of internal and external hemorrhoid.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physiology. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 239, 2nd~ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Anatomy of internal and external hemorrhoid.(Marcio J, Jorge N: Anorectal anatomy and physiology. In Beck DE, Wexner

SD [eds]: Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery, p. 239, 2nd~ed. London, WB

Saunders, 1998.)

Coronal section of the anal canal demonstrating the external and internal

sphincters and the longitudinal muscle bundles.(Illustrations 1–6 by Lisa Peñalver.)

Coronal section of the anal canal demonstrating the external and internal

sphincters and the longitudinal muscle bundles.(Illustrations 1–6 by Lisa Peñalver.)

The external anal sphincter is formed from three muscle loops.

The external anal sphincter is formed from three muscle loops.

Both continence (top) and defecation (middle and bottom) require interaction between the muscles of the anal sphincter.

Both continence (top) and defecation (middle and bottom) require interaction between the muscles of the anal sphincter.

Back to Top

Breasts

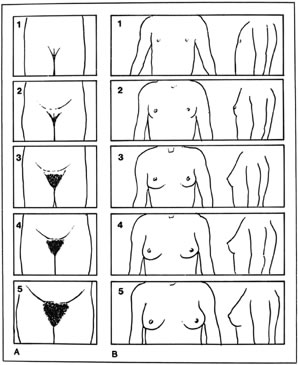

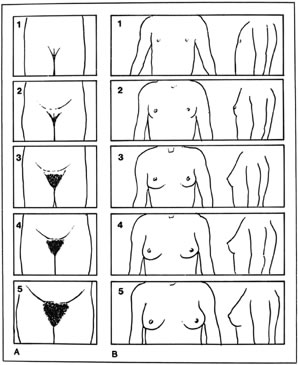

Female Tanner staging.

Female Tanner staging.

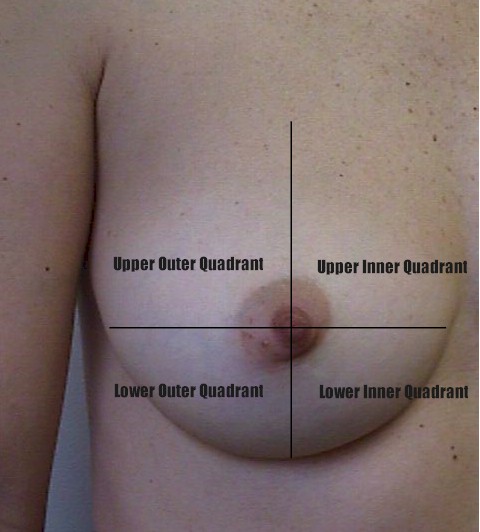

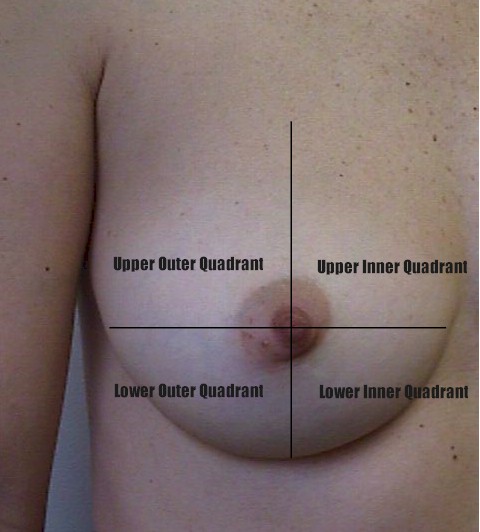

Breast quadrants.

Breast quadrants.

(Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD, All

rights reserved.)

Back to Top

Abdominal Wall

Torso of a 30-year-old multipara.

Torso of a 30-year-old multipara.

(Reproduced, with permission from Michael Hughey, MD,

All rights reserved.)

Superficial structures of the abdominal musculature and rectus sheath. Note

that the muscular fibers of the internal oblique layer lie nearer

the midline than those of the external oblique.(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1950)

Superficial structures of the abdominal musculature and rectus sheath. Note

that the muscular fibers of the internal oblique layer lie nearer

the midline than those of the external oblique.(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1950)

Deep structures of the abdominal musculature and rectus sheath. The fiber

directions of the transversus abdominis muscle are similar to those

of the internal oblique muscle seen in Figure 1. The semicircular line forms the caudal termination of the posterior rectus

sheath.(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1950)

Deep structures of the abdominal musculature and rectus sheath. The fiber

directions of the transversus abdominis muscle are similar to those

of the internal oblique muscle seen in Figure 1. The semicircular line forms the caudal termination of the posterior rectus

sheath.(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1950)

Inner surface of the abdominal wall. The bladder is highest in the midline, and

the midline urachus extends cranially from its apex. The lateral

umbilical ligaments and the inferior epigastric vessels lie beside

it. The semicircular line is marked (*).(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 1950)

Inner surface of the abdominal wall. The bladder is highest in the midline, and

the midline urachus extends cranially from its apex. The lateral

umbilical ligaments and the inferior epigastric vessels lie beside

it. The semicircular line is marked (*).(Anson BJ: Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 1950)

Pfannenstiel incision. (Parsons L, Ulfelder H:

Pfannenstiel incision. (Parsons L, Ulfelder H:

An Atlas of Pelvic Operations. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1968)

Maylard incision. The belly of the rectus muscle is elevated and cut. Deep

inferior epigastric vessels are usually incised but can also be left

intact if more lateral exposure is not needed.(Parsons L, Ulfelder H: An Atlas of Pelvic Operations. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1968)

Maylard incision. The belly of the rectus muscle is elevated and cut. Deep

inferior epigastric vessels are usually incised but can also be left

intact if more lateral exposure is not needed.(Parsons L, Ulfelder H: An Atlas of Pelvic Operations. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1968)

Paramedian incision. After incision of the rectus sheath and dissection

between the recti, the posterior sheath is incised and the peritoneal

incision is extended.(Parsons L, Ulfelder H: An Atlas of Pelvic Operations. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1968)

Paramedian incision. After incision of the rectus sheath and dissection

between the recti, the posterior sheath is incised and the peritoneal

incision is extended.(Parsons L, Ulfelder H: An Atlas of Pelvic Operations. Philadelphia, WB

Saunders, 1968)

Techniques of abdominal wall closure. A. Layered closure. B. Modified Smead-Jones closure. C. Mass closure. D. Retention suture.

Techniques of abdominal wall closure. A. Layered closure. B. Modified Smead-Jones closure. C. Mass closure. D. Retention suture.

Back to Top

Nerves

Nerves of the female genital tract. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division

of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from

the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All

rights reserved.)

Nerves of the female genital tract. (© 1977 CIBA Pharmaceutical Co, Division

of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from

the CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All

rights reserved.)

Retractor inductor nerve injury.(Vosburg

LF, Finn WF: Fernoral nerve impairment subsequent to hysterectomy. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 82: 931, 1961)

Retractor inductor nerve injury.(Vosburg

LF, Finn WF: Fernoral nerve impairment subsequent to hysterectomy. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 82: 931, 1961)

Location of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves that can be injured

during transverse abdominal incisions, as well as incisions in the

groin.(Skandalakis JE, Gray SW, Rowe JS: Anatomical Complications in General

Surgery. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1983)

Location of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves that can be injured

during transverse abdominal incisions, as well as incisions in the

groin.(Skandalakis JE, Gray SW, Rowe JS: Anatomical Complications in General

Surgery. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1983)

Diagram of the sympathetic connections in the female pelvis, viewed from

the front and above.

Diagram of the sympathetic connections in the female pelvis, viewed from

the front and above.

Back to Top

Blood Vessels

Surgical anatomy of pelvic circulation.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Surgical anatomy of pelvic circulation.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Cross-section of pelvis below level of bifurcation of common iliac artery, showing

retroperitoneal relationship of ureter.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Cross-section of pelvis below level of bifurcation of common iliac artery, showing

retroperitoneal relationship of ureter.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Lateral view of pelvic vessels, peritoneum removed.(Modified from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. Ferguson LK [trans]. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

Lateral view of pelvic vessels, peritoneum removed.(Modified from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. Ferguson LK [trans]. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

Lateral view of pelvic vessels, peritoneum present.(Modified from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. Ferguson LK [trans]. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

Lateral view of pelvic vessels, peritoneum present.(Modified from von Peham H, Amreich J: Operative Gynecology. Ferguson LK [trans]. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1934)

Collateral circulation in pelvis.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Collateral circulation in pelvis.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Common variations in “hypogastric axis.” 1, common iliac artery; 2, middle sacral artery; 3, external iliac artery; 4, internal iliac artery; 5, iliolumbar artery; 6, lateral sacral artery; 7, internal pudendal artery; 8, inferior gluteal artery; 9, middle hemorrhoidal artery; 10, inferior vesical artery; 11, uterine or deferential artery; 12, umbilical artery; 13, obturator artery; 14, superior gluteal artery.(Shafiroff BGP, Grillo EB, Baron H: Bilateral ligation of the hypogastric

arteries. Am J Surg 98:34, 1959)

Common variations in “hypogastric axis.” 1, common iliac artery; 2, middle sacral artery; 3, external iliac artery; 4, internal iliac artery; 5, iliolumbar artery; 6, lateral sacral artery; 7, internal pudendal artery; 8, inferior gluteal artery; 9, middle hemorrhoidal artery; 10, inferior vesical artery; 11, uterine or deferential artery; 12, umbilical artery; 13, obturator artery; 14, superior gluteal artery.(Shafiroff BGP, Grillo EB, Baron H: Bilateral ligation of the hypogastric

arteries. Am J Surg 98:34, 1959)

Aberrant artery causing ureteral obstruction. A. Schematic drawing from a cadaver showing bladder retracted to left and

a band of fibrous tissue, artery, and vein crossing ureter at right angle. B. Bladder has been pulled anteriorly, exposing lower ureter and seminal

vesicles and showing artery from hypogastric encircling ureter. C. Bladder retracted to left side, showing a vein coming from external iliac

and looping about ureter.(Hyams J: Aberrant blood vessels as factors in lower ureteral obstruction: Preliminary

report. Surg Gynecol Obstet 48:474, 1929)

Aberrant artery causing ureteral obstruction. A. Schematic drawing from a cadaver showing bladder retracted to left and

a band of fibrous tissue, artery, and vein crossing ureter at right angle. B. Bladder has been pulled anteriorly, exposing lower ureter and seminal

vesicles and showing artery from hypogastric encircling ureter. C. Bladder retracted to left side, showing a vein coming from external iliac

and looping about ureter.(Hyams J: Aberrant blood vessels as factors in lower ureteral obstruction: Preliminary

report. Surg Gynecol Obstet 48:474, 1929)

Surgical technique: transabdominal approach.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Surgical technique: transabdominal approach.(Reich WJ, Nechtow MJ: Ligation of the internal iliac [hypogastric] arteries: A

life-saving procedure for uncontrollable gynecologic

and obstetric hemorrhage. J Int Coll Surg 36:157, 1961)

Pelvic blood vessels and nerves. Lumbosacral nerve trunk is indicated (+). (© 1977 CIBA

Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical

Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Pelvic blood vessels and nerves. Lumbosacral nerve trunk is indicated (+). (© 1977 CIBA

Pharmaceutical Co, Division of CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. Reproduced, with permission from the CIBA Collection of Medical

Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, M.D. All rights reserved.)

Back to Top |