Hyperemesis in Pregnancy

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Nausea and vomiting, the most commonly encountered clinical problems of early pregnancy, occur in approximately 50% to 90% of all pregnancies.1,2 Many pregnant women do not seek treatment because of concerns about safety of medications during pregnancy. In contrast, hyperemesis gravidarum occurs in only .3% to 2% of all pregnancies but accounts for 30% of hospital admissions before 20 weeks.3

The nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is a spectrum in which 25% of pregnant women have no symptoms, 25% have nausea only, and 50% experience both nausea and vomiting. NVP may also be described as a continuum from mild (nausea only) to moderate (nausea and vomiting) to severe (intractable vomiting leading to dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, ketonuria, weight loss greater than 5% of prepregnancy weight, or malnutrition requiring hospitalization). Mild to moderate NVP is equivalent to physiologic vomiting; severe NVP is the definition of hyperemesis gravidarum.4,5 Lacroix and associates concluded that NVP is comparable in severity to the nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy of moderately emetic potential.6

Epidemiologic investigations have associated hyperemesis gravidarum with multiple births, previous history of an unsuccessful pregnancy, nulliparity, hyperemesis gravidarum in a previous pregnancy, and obesity. In contrast, a low rate has been associated with wartime conditions, advanced maternal age, and a history of cigarette smoking.1,2,5

CLINICAL COURSE

NVP can begin as early as blastocyst implantation. The mean gestational age of onset is 5 to 6 weeks from the last menstrual period. The prevalence and the severity of those affected with NVP peaks at 9 to 11 weeks. By 14 weeks, 50% noted resolution of their symptoms, and not until 22 weeks did 90% find complete relief from symptoms. In 40% of women, symptoms stopped suddenly; 10% to 15% of NVP persisted all through the pregnancy. In patients who had NVP persisting through the second and third trimester, the intensity of nausea remained stable.6

Symptoms were limited to the morning only in less than 2% of women; 80% reported nausea lasting all day.6 Fifty-three percent of vomiting occurred between 06:00 and 12:00, with symptom incidence scattered throughout the waking hours, making the condition best described as episodic daytime pregnancy nausea and vomiting.1 Retrospective data reveal the recurrence risk for hyperemesis gravidarum to be approximately 66%.1

Of the women employed outside of the home, the mean days lost from work because of NVP since the start of symptoms was 14.0 days. The total societal cost of reported health care resource use and time lost from work was $2947 per patient with severe NVP.7

Hospitalization and time lost from work are the largest components of the total per patient cost. Gadsby and associates reported an average of 62 hours of lost employed work and 32 hours of lost household work.1 NVP has a pervasive and detrimental impact on family, social, and professional lives.

DIAGNOSIS

The presence of persistent and intractable nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy can lead to weight loss and, in severe cases, tachycardia, hypotension, dry mucosa, and loss of skin turgor caused by chronic dehydration. Mild jaundice and a ketotic odor in the breath may be observed in some patients. Ptyalism commonly occurs. Rarely encountered today are hyperpyrexia, albuminuria, and peripheral neuritis. In neglected cases, ophthalmoplegia, gait ataxia, confusion (the classic triad of Wernicke's encephalopathy caused by vitamin B deficiency) may be present.5 Other maternal complications caused by prolonged retching include Mallory-Weiss tear, esophageal rupture, pneumothorax, splenic avulsion, and Wernicke's encephalopathy.4 Today, hyperemesis gravidarum rarely causes death. However, left untreated, the effects include maternal neurological, renal, retinal, and hepatic damage similar to changes observed in starvation. Also, hyperemesis gravidarum can have an impact on the psychological and financial status on the family. Psychosocial morbidity among women with NVP included irritability, sleep disturbances, and increased fatigue. Feelings of depression were reported by more than 50% of women with NVP.8

The presence of abdominal pain that precedes and is out of proportion to the nausea and vomiting, headaches, abnormal neurological examination, or the presence of goiter should lead to a workup for conditions other than NVP.

Laboratory findings of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities include elevated hematocrit and blood urea nitrogen, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis with paradoxical aciduria. Urinalysis reveals ketonuria and increased urine-specific gravity. Half of women hospitalized for hyperemesis gravidarum have abnormal liver function test results, including elevated bilirubin (less than 4 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (twice the normal), and aminotransferase (increased up to 200 U/L). Liver biopsy specimens in these cases may show fatty changes or cholestasis with hepatocyte necrosis. The mechanism of hyperbilirubinemia is unknown, but it is thought to be related to malnutrition and impaired excretion of bilirubin. Liver function test results return to normal within days after the resumption of adequate nutrition.9 For a summary of the potential biochemical abnormalities seen in hyperemesis gravidarum, see Table 1. It should be noted that all tests return to normal after NVP has been resolved.

Table 1. Biochemical Abnormalities in Hyperemesis Gravidarum

| Abnormality | Incidence (%) |

| Thyroid | |

| Increased free T4 index | 59 |

| Increased free T3 index | 9 |

| TSH | |

| undetectable | 30 |

| suppressed | 60 |

| Electrolytes | |

| Sodium <135 mEq/L | 28 |

| Potassium <3.2 mEq/L | 15 |

| Chloride <99 mEq/L | 24 |

| Bicarbonate >26 mEq/L | 15 |

| Liver/gastrointestinal | |

| Aminotranferase >40 u/L | 42 |

| Total bilirubin >1.0 mg/dL | 21 |

| Amylase >150 U/d/L | 9 |

(Adapted from Goodwin TM, Hershman JM: Hyperthyroidism due to inappropriate production of human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Obstet Gynecol 40:32, 1997.)

An ultrasound examination should be performed to identify predisposing factors for hyperemesis gravidarum such as multiple gestation and molar gestation.

Sheehan's10 findings on 19 autopsies of patients who died of hyperemesis gravidarum included evidence of loss of weight, heart muscle atrophy, presence of fat in the mitochondrial zone of the proximal convoluted tubules of kidneys, centrilobular or periportal fatty infiltration of the liver, and the cerebral lesions of Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Although the diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum is made clinically, other causes of nausea and vomiting must be excluded (Table 2). Symptoms of NVP usually present before 10 weeks of gestation. If symptoms present after 10 weeks of gestation, other conditions must be considered.

Table 2. Causes of Nausea and Vomiting During Pregnancy

| Gastrointestinal Causes | Obstetric Causes |

| Acid peptic disorders | Hydatidiform mole |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | Multifetal gestation |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | Pregnancy induced hypertension |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | Hydramnios |

| Appendicitis | Placental abruption |

| Inflammatory/obstructive bowel disease | |

| Gynecologic Causes | |

| Hepatobiliary Causes | Ovarian torsion |

| Cholecystitis | Red degeneration of fibroids |

| Hepatitis | |

| Biliary tract disease | Endocrine/Metabolic causes |

| Pancreatitis | Hyperthyroidism |

| Diabetes | |

| Urinary Causes | |

| Uremia | Miscellaneous |

| Pyelonephritis | CNS lesions |

| Drug toxicity | |

| Vestibular disease |

PREGNANCY OUTCOME

Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy have been viewed as a prognostic factor of pregnancy outcome. Studies of women with nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy have shown a statistically significant decrease in the risk of miscarriage in the first 20 weeks of gestation.5 Not all studies, however, have demonstrated a protective effect of hyperemesis gravidarum against miscarriage.11 Mazotta and colleagues found that 1.5% (17/1100) of women terminated their pregnancies because of severe NVP.12

In severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum with a greater than 5% weight loss and long-term malnutrition, adverse pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight, antepartum hemorrhage, and preterm delivery have been reported.13 Central nervous system malformations and integumentary abnormalities (e.g., webbed toes, skin tags) have been reported in infants of women with hyperemesis.11,14 Chin and Lao found an association between severe NVP and intrauterine growth retardation.15 Several studies, however, have questioned these findings and concluded that women with hyperemesis gravidarum have obstetric outcomes similar to those of the general obstetric population.16,17 No data on infant risks beyond birth outcomes are available.

ETIOLOGY

The pathogenesis of hyperemesis gravidarum is still not well understood. Goodwin proposed NVP as a syndrome with genetic and environmental components.18 He theorized that a primary stimulus, possibly a hormone of placental origin, was modified during production by both genetic and specific disease states. Hormonal response may be modified at the receptor level (e.g., glycoprotein hormone or estrogen receptor). The maternal physiologic response may be modified by the major pathways (vestibular, gastrointestinal, olfactory, and gustatory) leading to nausea and vomiting. Behavioral and psychological factors modify the primary symptoms and cause the clinical impact of the condition.

GENETIC FACTORS

A positive family history for NVP,19 the variation in frequency between ethnic groups, the concordance in monozygotic twins,20 and the occurrence of NVP in women with inherited glycoprotein hormone (TSH) receptor defects21 act as evidence in support of a genetic predisposition to NVP.

PRIMARY STIMULUS

It has been proposed that gestational hormones, especially human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), may be associated with hyperemesis because of the increased incidence in cases of multiple gestation and molar pregnancy. The fact that the time when hCG levels peak (6–12 weeks after the last menstrual period) coincides with the time when hyperemesis is most common has been cited as further evidence of this relationship.22 Response to the stimulus may be mediated by genetic variation in the receptor–ligand interaction. The initial response may also be influenced by the susceptibility of the mother to stimulation of the major pathways to nausea and vomiting.

Serum concentrations of maternal estrogens, progesterone, adrenal corticotropic hormones, serotonin, and Schwangerschaft protein (SP-1) have been studied, but an etiologic role in hyperemesis gravidarum has not been clearly defined.23,24 During the past 25 years, 17 reports have studied the relationship between nonthyroid hormones and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Only hCG and estradiol25 have shown any association.

Women with miscarriage are at decreased risk for NVP.26 This is further support for the hypothesis that abnormal placentation results in reduced production of hCG or estrogen, which may trigger NVP.

METABOLIC FACTORS

Transient hyperthyroidism of hyperemesis gravidarum, also referred to as gestational thyrotoxicosis by some investigators, has been associated with inappropriate secretion of hCG. Several studies have shown that deglycosylated, desiaylated hCG has enhanced thyrotropic potency and has been found in the serum of women with moles and severe hyperemesis gravidarum.27,28,29 Transient hyperthyroidism is seldom associated with clinically overt hyperthyroidism and thyroid antibodies are usually absent.30 With control of NVP, thyroid studies revert to normal after days to weeks with no sequelae.

Altered lipid metabolism, liver dysfunction, and hyperparathyroidism are some of the other metabolic disorders that have been proposed as causal factors of hyperemesis gravidarum.31 Studies have been inconclusive.

Women with hyperemesis gravidarum have reduced basal oxygen consumption and a reduced basal metabolic rate, similar to a state of starvation.32 However, in hyperemesis gravidarum, this occurs despite an increase in thyroid activity.

THE VESTIBULAR SYSTEM

Whitehead and colleagues33 surveyed 1000 women with NVP between 14 and 28 weeks' gestation and found that 12% had a history of motion sickness; the frequency of vomiting during pregnancy was significantly higher in patients with motion sickness.

GASTROINTESTINAL DYSMOTILITY

Recent studies suggest that reflux esophagitis in association with delayed gastric emptying and disturbance in the gastric myoelectrical activity, also known as gastric dysrhythmias, can trigger vomiting as a result of changes in the gastric pH.22 Women with subclinical gastric motor dysfunction who become pregnant may be more susceptible to NVP.34

TASTE AND OLFACTION

Taste, which is closely linked to olfaction, is genetically controlled. So-called super tasters are more likely to experience NVP than those who are less sensitive to bitter taste perception.35 Odors are associated with pregnancy-related nausea. In fact, only a small percentage of women with congenital anosmia have NVP.36Many of the same stimuli trigger an attack of migraine in susceptible women, and a genetic link between migraine and NVP has been proposed.36

BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING OF PREGNANCY

Poor communication with either the husband or the obstetrician, stress, doubts, and inadequate information about pregnancy have been correlated with nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Psychiatric diagnoses commonly associated with hyperemesis gravidarum include immature personality associated with hysteria, strong maternal dependence, conversion disorder, and protest reaction against pregnancy because of psychological conflicts.4 The inclusion into the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders of the category “psychogenic hyperemesis gravidarum” denotes the accepted role of psychological factors in the evolution of hyperemesis gravidarum. A psychiatric consult may be indicated to evaluate any evidence of secondary gain.

It is increasingly recognized that a behavioral-mediated, anticipatory nausea and vomiting contributes to NVP. Reports of successful therapy of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy with behavioral modification and hypnosis support this hypothesis.37

TREATMENT

The management of NVP depends on the severity of the illness, ranging from supportive/alternative remedies for mild NVP to use of nutritional support and pharmacologic therapies for severe NVP.38

MILD NAUSEA AND VOMITING OF PREGNANCY

Mild NVP usually responds well to conservative management. The patient should be given the following guidelines.

Modify the environment. Avoid strong odors such as cigarette smoke, cooking odors, perfumes, or petroleum-containing products that can induce nausea or vomiting in some women.

Modify the diet.39,40 Eliminate spicy, fried, or greasy foods. The smell of cooking foods, particularly meats, and especially bacon, often trigger to nausea. Eat small, frequent meals, because empty and full stomachs are less well-tolerated than a partially filled stomach. Avoid a particularly nauseating food, or eat bland and dry, diet-like crackers at certain times of the day. Have a variety of food types available, because each woman with this disorder reacts differently to the smells, textures, colors, and flavors of different foods. Sometimes liquids are not tolerated, and fruit can help meet fluid needs. Try eating high-carbohydrate low-fat meals. Try eating protein-predominant meals.41 Try drinking small amounts of cold, carbonated, clear or sour liquids. Drink between meals rather than with meals.

Avoid iron tablets, a common side effect of which is nausea. These should be changed or withheld for a time until the patient can better tolerate them.

Consider alternative therapies. Acupressure wristbands worn to prevent motion sickness effectively reduce nausea (but not vomiting) in some women.42 Stimulation of the P6 (Neiguan) point on the inner aspect of the wrist has been use by acupuncturists. Jewell and Young evaluated the published studies on using acupressure for NVP and concluded that the evidence is mixed; it has not been shown to be clearly effective.43 Herbal remedies, including raspberry, peppermint, spearmint, fennel, anise, and ginger teas may be helpful. Ginger capsules (250 mg four times per day or 500 mg three times per day) have been shown to give relief. Two controlled trials used ground ginger capsules, 250 mg four times per day, in the treatment of NVP.44,45 In the first trial, 70% of women reported feeling less nausea during the ginger phase of therapy. In the more recent study, there was a significant decrease in nausea (by visual analog scale) and in the number of episodes of vomiting in the ginger group compared with placebo. Ginger is not known to be teratogenic, although no large-scale studies have been performed. Ginger ale may also be helpful.

Emetrol, a cola-flavored drink that inhibits smooth muscle, may alleviate symptoms in some women.

Supportive psychotherapy entails establishment of positive feelings.4

Hypnotherapy consists of trance induction and suggestions for comfort in the gastrointestinal tract, the desirability of feeling substances in the stomach, and the ability to retain and digest food.46

Behavior modification provides positive reinforcement for retaining food and gaining weight through granting desirable considerations and positive feedback, such as having visitors, enjoying radio and television, and being able to get up in or outside the room.

Sensory afferent stimulation, like transcutaneous nerve stimulation, has also been studied for use in hyperemesis gravidarum, but this requires further investigation.22 Finally, the obstetrician should offer the patient emotional support and reassure her about the transient nature of the condition and the generally excellent prognosis.

SEVERE NAUSEA AND VOMITING OF PREGNANCY (HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM)

Approximately 10% of women will not respond to the aforementioned remedies and pharmacologic therapy will be needed. It is best to proceed in a stepwise manner, starting with the mildest medication. Consider hospitalization when severe nausea and vomiting are accompanied by dehydration, electrolyte or metabolic disturbances, weight loss greater than 5% of total body weight, or malnutrition. This occurs in approximately 1% to 2% of cases.

MANAGEMENT OF DEHYDRATION AND ELECTROLYTE DISTURBANCES

Because of the physiologic increase in plasma volume during pregnancy, significant hypovolemia can occur before it is clinically recognized. Maternal hypovolemia can also trigger secretion of catecholamines, which can reduce uterine perfusion.

Hypovolemia, electrolyte imbalances, and ketosis can be corrected with intravenous fluids. Ringer's solution with 5% dextrose is recommended over 5% dextrose in .9% sodium chloride solution, because it supplies potassium and calcium. Also, lactated Ringer's solution has shown to be more physiologic and more effective in restoring fetal oxygen levels. Large quantities of normal saline can cause maternal and fetal hyperchloremic acidosis. Intake and output determinations and daily weight should be obtained to aid in fluid status assessment. Nothing should be taken by mouth until the dehydration has been corrected and vomiting controlled.

Parenteral vitamins should be administered if there has been a prolonged course of vomiting. Vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), C, and K have been shown to be effective. Thiamine (100 mg daily, intramuscularly or intravenously) has been recommended. Wernicke's encephalopathy can result if thiamine is not administered before intravenous dextrose administration. Replacement of water-soluble vitamins is important because body stores of these vitamins are depleted rapidly.

Electrolytes depleted by vomiting, particularly chloride and potassium, must be replaced. Magnesium depletion results from vitamin B6 depletion, and nausea results from magnesium deficiency. Uncorrected magnesium deficiency may also impair repletion of cellular potassium.

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

Decreased food intake and increased nutrient loss cause compromised nutritional status. Van Stuijvenberg and colleagues47 found that in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum, mean dietary intake of most nutrients was less than 50% of the recommended daily allowances, which was significantly lower than that of controls.

Hamaoui and Hamaoui48 theorized that the nausea that occurs in hyperemesis gravidarum could be related to the nausea that occurs in the fasting state. Nausea, according to them, is a severe form of masked hunger, which disappears once the patient is fed. Because of the increased caloric need during pregnancy, a state of constant hunger is said to exist. Compared with most other diseases associated with nausea, hyperemesis gravidarum is unique in that the nausea is relieved with gastric filling rather than emptying.

Nutritional assessment of pregnant women should address the following questions and decisions on further management made based on their assessment: (1) With what nutrient reserves has the woman entered pregnancy?; (2) What are her own physiologic needs, and what are the added requirements of her pregnancy?; (3)Does she have any disease process or is she receiving any therapy that might affect her nutrient requirement or nutrient tolerance?; and (4) Is her current intake meeting her nutritional needs?

Successful treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum with nasogastric tube feeding has been reported in the literature. The risk of enteral therapy, however, is aspiration pneumonia secondary to vomiting.49

Total parenteral hyperalimentation may be administered by either the peripheral lipid system or the central intravenous route. Central infusions are used whenever the therapy is long-term (at least 14 days) or when renal and/or cardiac impairment exists. Hyperemetic patients have had a favorable pregnancy outcome with the use of combination therapy consisting of dextrose, fat, protein, vitamins, trace elements, and electrolytes. Nevertheless, experience has demonstrated possible toxic, metabolic, and infectious complications of parenteral hyperalimentation; therefore, careful monitoring and strict protocols are required. Parenteral hyperalimentation is also expensive, and its application should be considered carefully.5 A retrospective, matched-control study has determined that home therapy for patients with hyperemesis gravidarum is safer, more efficacious, and more cost-effective than hospitalization.50

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Use of antiemetic drug therapy is justified only if there is a danger to maternal or fetal well-being. Patients should be counseled about safety issues before beginning medications. The safety and effectiveness of the different medications have been reviewed.51 All agree that medication should be administered in a stepwise fashion.

VITAMINS

The best-tested vitamin-based therapy for NVP is vitamin B6. Two controlled trials52,53 have shown efficacy of vitamin B6 to produce a marked reduction in nausea and vomiting; there is no evidence of teratogenicity.37 A randomized, placebo-controlled, prospective trial revealed that periconceptional multivitamin and mineral supplementation significantly reduced the incidence of pregnancy-induced vertigo, nausea, and vomiting.54

ANTIHISTAMINES

The mechanism of action of antihistamines is unknown, but they are clinically efficacious antiemetics. Doxylamine combined with pyridoxine (once marketed as Bendectin) was discontinued because of litigation over teratogenicity, which was shown to be untrue in controlled trials. Other commonly used antihistamines are buclizine, cyclizine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and meclizine. A meta-analysis of all controlled studies of the use of antihistamines in early pregnancy found them to be nonteratogenic.55 Pooled data indicate that antihistamines are effective in reducing vomiting in pregnancy, but the studies are not homogeneous. All antihistamines have drowsiness as a possible side effect.56,57

The combination of B6 and doxylamine has been continuously available as Diclectin in Canada, where it is the only drug approved for treatment of NVP. In the United States, it can be constituted by combining doxylamine (marketed over the counter as Unisom Sleep tabs, 25 mg per tablet) with vitamin B6. One full tablet of Unisom can be taken at night and half a tablet in the morning and afternoon along with vitamin B6 (25 mg three times per day). One difference between the combination of B6 and doxylamine and Diclectin is that Diclectin is a delayed-release formulation.

ANTICHOLINERGICS

Only dicyclomine and scopolamine are used for treatment of nausea and vomiting in the nonpregnant population. No trials demonstrating effectiveness for NVP have been published.

DOPAMINE ANTAGONISTS

A number of dopamine antagonists may be used to treat NVP: metoclopramide, domperidone, droperidol, trimethobenzamide, and the phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine, perphenazine, prochlorperazine, promethazine, and trifluoperazine).

Metoclopramide has been used throughout pregnancy with excellent results. It acts by increasing gastrointestinal motility and is superior in efficacy to placebo. Only one study addressed the safety and effectiveness of first trimester use, and showed no evidence of being teratogenic.58

Domperidone was not teratogenic in animals but there are no published observational or trial data of its use in human pregnancy.57 Trimethobenzamide has also been used with good results. One study suggested an increase in congenital anomalies, which was not confirmed in a follow-up study.59

Droperidol (a dopamine antagonist that is more potent than the phenothiazines) in combination with diphenhydramine (an antihistamine and anticholinergic), administered as a continuous infusion were found to be useful in managing hyperemesis in one study. No adverse fetal, neonatal, or maternal outcomes were noted.3 The FDA has published a black box warning about use of droperidol after it was shown it can prolong the QT-interval on EKG and cause potentially life-threatening torsade de pointes ventricular tachycardia. Deaths have been reported with less than standard doses. All patients need a 12-lead EKG before, during, and 3 hours after administration of droperidol.

The phenothiazines are best reserved for inpatient management of hyperemesis gravidarum. The antihistaminic phenothiazine promethazine is safe and effective. Although one study showed an increased incidence of birth defects, most studies have shown chlorpromazine to be safe for the fetus. Prochlorperazine has been evaluated in several studies, which have found no increased risks of birth defects. Compared with the antihistamines, phenothiazines have more serious side effects, such as orthostatic hypotension, sedation, tremor, extrapyramidal (Parkinsonian) effects, and skin reactions. They can also potentiate the effects of other drugs and alcohol.22

SEROTONIN ANTAGONIST

Ondansetron is a serotonin-receptor antagonist that acts as a potent antiemetic. The most common side effects are headache and mild sedation. A recent report showed ondansetron to be no more effective than promethazine for hyperemesis gravidarum in a hospital setting.60 There have been no reports of a teratogenic effect. There are no controlled human studies on the safety or effectiveness of either granisetron or tropisetron in pregnancy.

CORTICOSTEROIDS

That the corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone, methylprednisolone) may be effective for NVP has stemmed from the hypothesis that severe NVP may result from ACTH deficiency.61 Corticosteroids have been used to control chemotherapy-induced emesis. A number of reports have described successful use of corticosteroids for hyperemesis gravidarum.61,62,63,64,65 Corticosteroids should be reserved for patients whose symptoms have not responded to “conventional” antiemetics. In a recent meta-analysis, the pooled relative risk for major malformations was not significantly increased. However, a significant but small increase in oral clefts was found in pooled studies examining the association between corticosteroids use and oral clefts. These drugs should be discontinued if no response is observed within 3 days. Limit overall use to 6 weeks. Calcium supplementation 1200 mg per day is recommended.

Finally, there have been case reports of the successful use of antidepressants (mirtazapine) for NVP.66

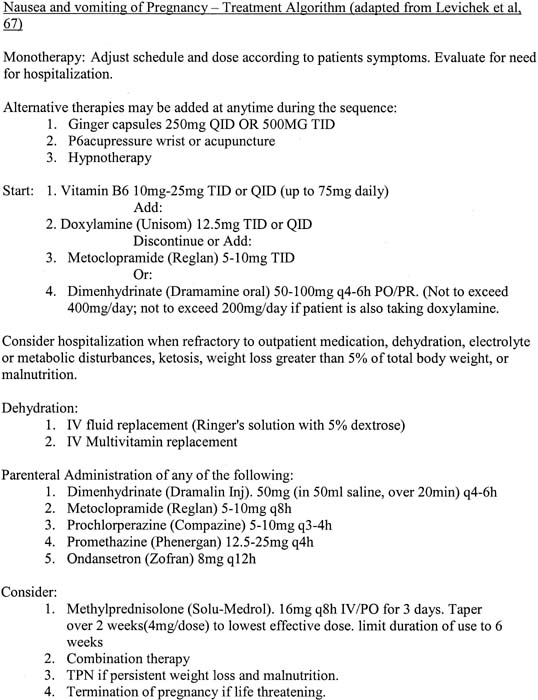

The Motherisk Program at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada67 has produced a drug treatment algorithm for NVP (Fig. 1).

|

|

REFERENCES

Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead AM, Jagger C: A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Br J Gen Pract 43:245-248, 1993 |

|

Klebanoff MA, Koslowe PA, Kaslow Rhoads GG: Epidemiology of vomiting in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 66:612-616, 1985 |

|

Nageotte MP, Briggs GG, Towers CV et al: Droperidol and diphenhydramine in the management of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:1801-1805, 1996 |

|

Deuchar N: Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A review of the problem with particular regard to psychological and social aspects. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 102:6-8, 1995 |

|

Hod M, Orvieto R, Kaplan B, Friedman S et al: Hyperemesis gravidarum. A review J Reprod Med 39:605-612, 1994 |

|

Lacroix R, Eason E, Melzack R: Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: A prospective study of its frequency, intensity, and patterns of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182:931-937, 2000 |

|

Attard CL, Kohli MA, Coleman S et al: The burden of illness of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:S220-S227, 2002 |

|

Mazzotta P, Stewart D, Atanackovic G et al: Psychosocial morbidity among women with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Prevalence and association with anti-emetic therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 21:129-136, 2000 |

|

Knox TA, Olans LB: Liver disease in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:569-576 |

|

Sheehan HL: The pathology of hyperemesis and vomiting of late pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Br Emp 46:685, 1939 |

|

Hallak M, Tsalamandris K, Dombrowski MP et al: Hyperemesis gravidarum. Effects on fetal outcome J Reprod Med 41:41:871-874, 1996 |

|

Mazotta P, Magee L, Koren G: Therapeutic abortions due to severe morning sickness. Unacceptable combination Can Fam Phys 43:1055-1057, 1997 |

|

Depue RH, Bernstein L, Ross RK et al: Hyperemesis gravidarum in relation to estradiol levels, pregnancy outcome, and other maternal factors: A seroepidemiologic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 156:1137-1141, 1987 |

|

Gross S, Librach C, Cecutti A: Maternal weight loss associated with hyperemesis gravidarum: A predictor of fetal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160:906-909, 1989 |

|

Chin RK, Lao TT: Low birth weight and hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 28:179-183, 1988 |

|

Bashiri A, Neumann L, Maymon E et al: Hyperemesis gravidarum: Epidemiologic features, complications and outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 63:135-138, 1995 |

|

Tsang IS, Katz VL, Wells SD: Maternal and fetal outcomes in hyperemesis gravidarum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 55:231-235, 1996 |

|

Goodwin TM: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: An obstetric syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:S184-S189, 2002 |

|

Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead AM, Jagger C: Pregnancy nausea related to women's obstetric and personal histories. Gynecol Obstet Invest 43:108-111, 1997 |

|

Corey LA, Berg K, Solaas MH et al: The epidemiology of pregnancy complications and outcome in a Norwegian twin population. Obstet Gynecol 80:989-994, 1992 |

|

Rodien P, Bremont C, Sanson ML et al: Familial gestational hyperthyroidism caused by a mutant thyrotropin receptor hypersensitive to human chorionic gonadotropin. N Engl J Med 339:1823-1826, 1998 |

|

Goodwin TM, Hershman JM, Cole L: Increased concentration of the free beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin in hyperemesis gravidarum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 73:770-772, 1994 |

|

Broussard CN, Richter JE: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 27:123-151, 1998 |

|

Borgeat A, Fathi M, Valiton A: Hyperemesis gravidarum: Is serotonin implicated. ? Am J Obstet Gynecol 176:476-477, 1997 |

|

Lagiou P, Tamimi R, Mucci LA et al: Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy in relation to prolactin, estrogens, and progesterone: A prospective study. Obstet Gynecol 101:639-644, 2003 |

|

Weigel RM, Weigel MM: Nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. A meta-analytical review Br J Obstet Gynaecol 96:1312-1318, 1989 |

|

Goodwin TM, Hershman JM: Hyperthyroidism due to inappropriate production of human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Obstet Gynecol 40:32-44, 1997 |

|

Kimura M, Amino N, Tamaki H et al: Gestational thyrotoxicosis and hyperemesis gravidarum: Possible role of hCG with higher stimulating activity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 38:345-350, 1993 |

|

Mestman JH: Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 27:127-149, 1998 |

|

Tan JY, Loh KC, Yeo GS et al: Transient hyperthyroidism of hyperemesis gravidarum. Br J Obstet Gynecol 109:683-688, 2002 |

|

Abell TL, Riely CA: Hyperemesis gravidarum. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 21:835-849, 1992 |

|

Chihara H, Otsubo Y, Yoneyama Y et al: Basal metabolic rate in hyperemesis gravidarum: Comparison to normal pregnancy and response to treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:434-438, 2003 |

|

Whitehead SA, Andrews PLR, Chamberlain GVP: Characterisation of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: A survey of 1000 women. J Obstet Gynaecol 12:364-369, 1992 |

|

Koch KL, Stern RM, Vasey M et al: Gastric dysrhythmias and nausea of pregnancy. Dig Dis Sci 35:961-968, 1990 |

|

Sipiora ML, Murtaugh MA, Gregoire MB et al: Bitter taste perception and severe vomiting in pregnancy. Physiol Behav 69:259-267, 2000 |

|

Heinrichs L: Linking olfaction with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, recurrent abortion, hyperemesis gravidarum, and migraine headache. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:S215-S219, 2002 |

|

Callahan E, Burnett M, DeLawyer D et al: Behavioral treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Pschosom Obstet Gynaecol 5:187-195, 1986 |

|

Peleg D, Niebyl J: Prescribing antiemetic therapy during pregnancy. Contemp Obster Gynecol 42:164-171, 1997 |

|

Kolasa KM, Weismiller DG: Nutrition during pregnancy. Am Fam Phys 56:205-212, 1997 |

|

Newman V, Fullerton JT, Anderson PO: Clinical advances in the management of severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonat Nurs 22:483-490, 1993 |

|

Jednak MA, Shadigian EM, Kim MS et al: Protein meals reduce nausea and gastric slow wave dysrhythmic activity in first trimester pregnancy. Am J Physiol 277:G855-G861, 1999 |

|

Hoo JJ: Acupressure for hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176:1395-1397, 1997 |

|

Jewell D, Young G: Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD000145, 2002 |

|

Vutyavanich T, Kraisarin T, Ruangsri R: Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 97:577-582, 2001 |

|

Fischer-Rasmussen W, Kjaer SK, Dahl C et al: Ginger treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 38:19-24, 1991 |

|

Torem MS: Hypnotherapeutic techniques in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Clin Hypn 37:1-11, 1994 |

|

van Stuijvenberg ME, Schabort I, Labadarios D et al: The nutritional status and treatment of patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 172:1585-1591, 1995 |

|

Hamaoui E, Hamaoui M: Nutritional assessment and support during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 32:59-121, 2003 |

|

Hsu JJ, Clark-Glena R, Nelson DK et al: Nasogastric enteral feeding in the management of hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 88:343-346, 1996 |

|

Naef RW 3rd, Chauhan SP, Roach H et al: Treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum in the home: An alternative to hospitalization. J Perinatol 15:289-292, 1995 |

|

Magee LA, Mazzotta P, Koren G: Evidence-based view of safety and effectiveness of pharmacologic therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:S256-S261, 2002 |

|

Sahakian V, Rouse D, Sipes S et al: Vitamin B6 is effective therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Obstet Gynecol 78:33-36, 1991 |

|

Vutyavanich T, Wongtra-ngan S, Ruangsri R: Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173:881-884, 1995 |

|

Czeizel AE, Dudas I, Fritz G et al: The effect of periconceptional multivitamin-mineral supplementation on vertigo, nausea and vomiting in the first trimester of pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 251:181-185, 1992 |

|

Seto A, Einarson T, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following first trimester exposure to antihistamines: Meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol 14:119-124, 1997 |

|

Mazzotta P, Magee LA: A risk-benefit assessment of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Drugs 59:781-800, 2000 |

|

Magee L, Mazzotta P, Koren G: Evidence-based view of safety and effectiveness of pharmacologic therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:S256-S261, 2002 |

|

Berkovitch M, Elbirt D, Addis A et al: Fetal effects of metoclopramide therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 343:445-446, 2000 |

|

Einarson A, Koren G, Bergman U: Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A comparative European study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 76:1-3, 1998 |

|

Sullivan CA, Johnson CA, Roach H et al: A pilot study of intravenous ondansetron for hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:1565-1568, 1996 |

|

Ylikorkala O, Kauppila A, Ollanketo ML: Intramuscular ACTH and placebo in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 58:453-455, 1979 |

|

Safari HR, Fassett MJ, Souter IC et al: The efficacy of methylprednisolone in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum: A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:921-929, 1998 |

|

Nelson-Piercy C, Fayers P, de Swiet M: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids for the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Br J Obstet Gynecol 108:9-15, 2001 |

|

Taylor R: Successful management of hyperemesis gravidarum using steroid therapy. QJM 89:103-107, 1996 |

|

APGO Educational Series On Women's Health Issues: Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy. 2001 |

|

Rohde A, Dembinski J, Dorn C: Mirtazapine (Remergil) for treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: Rescue of a twin pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 268:219–221, 2003 |

|

Levichek Z, Atanackovic G, Oepkes D et al: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Evidence based treatment algorithm Can Fam Phys 48:267-268, 2002 |